Post-publication careers: follow-up expeditions reveal avalanches at Dyatlov Pass Comments (12)

Johan Gaume for Dyatlovpass.com. In our new article in Communications Earth & Environment, we report five main findings relevant to the Dyatlov Pass incident:

- independent research by Pigol'tsyna and Popovnin confirm main assumptions and results of our modelling;

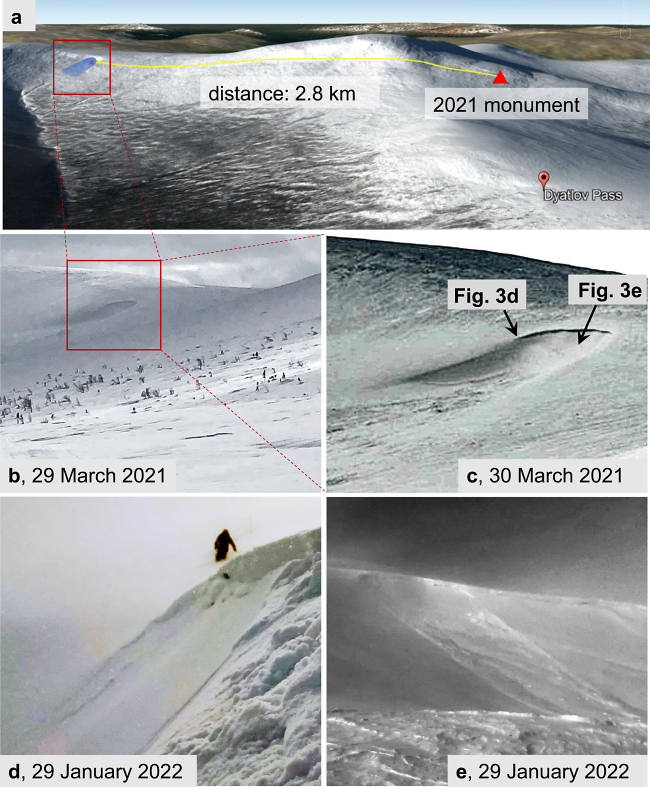

- based on a drone survey, we confirm that slopes above the potential tent location are steep enough for avalanches to happen; an expedition organized late January 2022 revealed the presence of slab avalanches in an eastern slope, less than 3km away from the Dyatlov group tent;

- in less than an hour, traces of the small slab avalanche (with a similar release size as the one assumed in our model) were erased because it was covered by wind-transported snow. This explains why the Dyatlov rescue team could not find avalanche signs above the tent 3 weeks after the incident. Snow observed on the tent and below it could be from the slab, as shown in our numerical simulations;

- such a short lifetime of avalanche traces also explains why no avalanches have been documented on these slopes in the past 60 years.

Dyatlovpass.com follow-up questions. Invisible avalanche? How do you answer these questions then:

Gaume: The avalanche is visible, audible and can break your ribs if it hits you when you are lying down. The release area of a small slab avalanche is quickly covered by the new snow and becomes difficult to detect. This is what Oleg and Dmitriy observed two months ago.

- How did the footprints and traces of urination happen to be on top of the slab avalanche?

Traces of urination were found at the entrance to the tent, where the pole survived and was still standing. This can indicate that the slab avalanche was rather small (about 5mx5 m according to our model) and it hit the part of the tent further away from the entrance. This can also explain why not all of them got injured.

- Why did the hikers go down abreast, slowly, without looking back along the path of the alleged avalanche?

The slab released above the tent was small, it hit the tent and stopped, because the slope inclination below the tent is very mild. The run-out of the avalanche according to our model was very short and did not exceed 1-2 meters below the tent. The hikers thus did not go down the path of the avalanche, they went down the undisturbed snow cover, leaving footprints in it.

- How and why were the dead and unconscious transported a mile down?

Based on our modeling, the injuries caused by the possible avalanche could be severe, but not fatal. Research by the San Diego hospital in collaboration with General Motors has shown that 6-12 broken ribs are not going to kill you. It is even possible to walk with such injuries with some help. But both in our original paper and now we do not insist that the injuries occurred in the tent. We just say that the slab was heavy enough to cause them, but we remain open to other possibilities (e.g., injuries in the ravine etc.).

You can comment at the bottom.

a. Location of the area where avalanches were observed. Source: Google Earth © 2021 Maxar technologies Landsat/Copernicus.

b. Picture taken by Dmitriy Borisov on the 29th of March 2021 from the Dyatlov Pass. The zone highlighted in red is located ~3 km away from the tent.

c. Picture extracted from a video taken by Matteo Born (RSI movie director), the day later, i.e., 30th March 2021.

d. Picture of a crown tensile fracture on the left side of this slope taken by Dmitriy Borisov on 29th January 2022.

e. Picture of a small slab avalanche in the middle of the slope by Dmitriy Borisov on the same day (29th January 2022).

The Swiss "avalanche" team Alexander Puzrin and Johan Gaume have a second paper in Nature.com Post-publication careers: follow-up expeditions reveal avalanches at Dyatlov Pass publishing data from expeditions to the Dyatlov Pass documenting avalanches on the other side of the pass, not on the side where the tent was, and 3D model showing plenitude of red spots where the terrain is close to 30° and they are high fiving since they used in their calculations 28° if I am correct, fact check me on this. Basically the scientific paper proves that a freak avalanche can happen on the Dyatlov Pass. There still need to be certain parameters present: combination of irregular topography, a cut made in the slope to install the tent and the subsequent deposition of snow induced by strong katabatic winds.

We are now not arguing if an avalanche can happen, Puzrin and Gaume convinced us that it could with their first publication Mechanisms of slab avalanche release and impact in the Dyatlov Pass incident in 1959 and this one only confirms it.

But the avalanche theory doesn't answer any of the questions that arise from the case files. It was the first theory that the investigation in 1959 looked into, and it was discarded not because there couldn't have been an avalanche, but because there was none.

The evidence in the case files shows no avalanche, and this new publication can't change that:

- Photos and witness testimonies from searchers that found the tent in February 1959 state there was no trace of avalanche. There were also documented traces of urination and footprints. How would this remain visible if there was an avalanche?

- Puzrin and Gaume say that the hikers cut open their tent because there was an avalanche. The case files contain photos of footprints going down along the path of the alleged avalanche, slowly, orderly, abreast. Not the behavior of people that are abandoning their tent to escape from an avalanche.

- Puzrin and Gaume say that the avalanche caused the lethal injuries on three of the hikers. The coroner testifies that they lived not more than 20-30 mins, one of them unconscious with a caved in skull. How did they get a mile down where the bodies were found?

What we should take from this paper is that if there was an avalanche in 1959, it should have been readily apparent to the first responders. Now you see what a slab avalanche looks like and know that there wasn't one on the photos taken in 1959.

| Teddy Hadjiyska | 27-04-2022 18:16 (GMT) |

| Teddy Hadjiyska | 24-04-2022 12:19 (GMT) |

| Teddy Hadjiyska | 24-04-2022 12:16 (GMT) |

1. The first is could there be an avalanche where the Dyatlov tent was found. I am not equipped to disprove their science but I am working with a Russian on a response with his own take on the avalanches in the area. He is proving this avalanche is not applicable to the place where the tent was found. Conditions are very different. And not to take this in account one must have blindfolds.

2. The second aspect of how they explain the whole incident doesn't have any weight or anything new to discuss. This scenario is disregarded even by the Russian officials. There are worse theories than theirs but they don't make all the headlines. This is what is out of balance.

| G. Ristaino | 24-04-2022 12:05 (GMT) |

| Ural Expeditions & Tours | 05-04-2022 07:35 (GMT) |

An avalanche was recorded for the first time in the area where the Dyatlov group died

В районе гибели группы Дятлова впервые зафиксирован сход лавины

https://www.gazeta.ru/science/news/2022/03/25/17475859.shtml

The first video with the consequences of an avalanche at the Dyatlov Pass has been published

Опубликовано первое видео с последствиями схода лавины на перевале Дятлова

https://www.gazeta.ru/science/news/2022/03/25/17477035.shtml

Glaciologist Popovnin spoke about the main evidence of the avalanche version in the case of the death of the Dyatlov group

Гляциолог Поповнин рассказал о главном доказательстве лавинной версии в деле о гибели группы Дятлова

https://www.gazeta.ru/science/news/2022/04/04/17518621.shtml

It swept up in 20 minutes. Found the first evidence of the death of the Dyatlov group under an avalanche

Замело за 20 минут. Найдено первое доказательство гибели группы Дятлова под лавиной

https://www.gazeta.ru/science/2022/03/25/14665783.shtml

"Prisms, cups or plates": what killed the Dyatlov group

«Призмочки, бокальчики, стаканчики»: что убило группу Дятлова

https://www.gazeta.ru/science/2022/04/04/14696185.shtml

| rainbo6003 | 02-04-2022 00:36 (GMT) |

None of the searchers who saw the scene testified that it was an avalanche.

It is clear that it was not an avalanche.

| Anna Dydyk | 01-04-2022 20:37 (GMT) |

| Tommy Maggitas | 01-04-2022 20:32 (GMT) |

| K.R. Rogers | 01-04-2022 20:31 (GMT) |

| Torbi Et Orbi | 01-04-2022 20:30 (GMT) |

| Emilia | 01-04-2022 18:22 (GMT) |

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/01/world/europe/dyatlov-pass-avalanche-russia.html

| Nutcracker | 31-03-2022 16:59 (GMT) |

I've attached the 3 most pertinent photos from the search, colourised and restored.

While some claim 3 week's worth of windblown snow would fill the void left by a slab slip breaking off, I'm not convinced it would do so completely or create such a firm surface that men could stand on it and not realize what had happened there.

And the only visible evidence of any potential avalanche was immediately below the tent site, where some 2 tones of snow (possible to calculate the volumetric weight online for snow crust) had been thrown when a tent trench was dug out, the large clumps which would survive the wind. (And some on the tent, along with a torch.)