Interview with Boris Gudkov

It all started when Tanya (Moon) decided to check whether the note from Moscow State University students, taken from one of the peaks of Otorten by Moisey Akselrod’s group in 1959, was real during the sad epic of the search for the Dyatlov group. This note indicated the names and surnames of the participants in the ascent to Otorten in July 1956. Tanya found the address of the leader of that group, Boris Sergeevich Gudkov, and wrote him a letter. After several letters to Boris Gudkov, Tanya shared his address with me. I asked for permission to send him questions about that trek and that time... Boris Sergeevich kindly agreed to answer them. We began a correspondence, which resulted in this publication. A wonderful invention, the Internet, given to people by God! Without it, it is unlikely that we could communicate so freely, quickly and easily, while being in different parts of the world, me in Spain, Boris Sergeevich in Moscow, Otorten in the Northern Urals, and we all connected at one point.

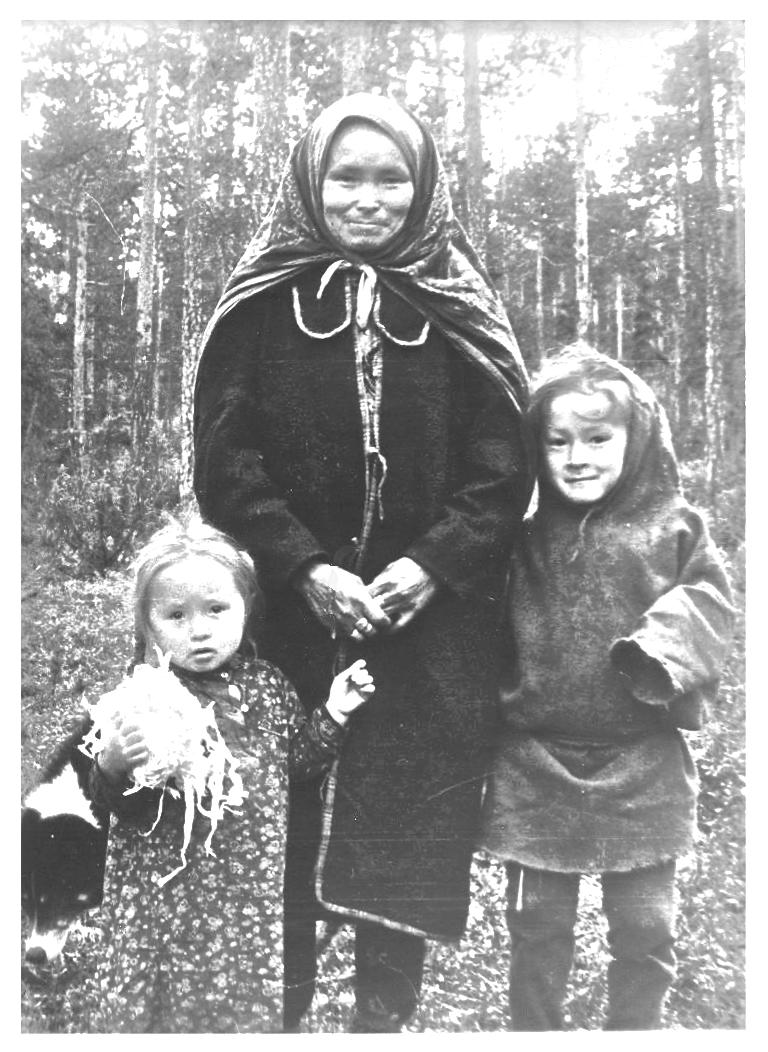

In the process of correspondence, Boris Sergeevich sent me notes about his student hiking life and the diary of his trek to Otorten in 1956, as well as photographs of this campaign and photographs of the Artybash camp site from the time when Semyon Alekseevich Zolotaryov worked there. I am pleased to present all this to the reader and express my gratitude for the materials provided, for the responsiveness and kindness in communication to a wonderful person - Boris Sergeevich Gudkov and, of course, Tatyana Vladimirovna!

In the text: B.G. - Boris Sergeevich Gudkov

M.P.: Dear Boris Sergeevich, thank you for agreeing to answer some questions and tell people about your expedition to Otorten. Thank you very much for the hiking diary! I just read it, it’s extremely interesting. You warned me that this diary is unlikely to help me find out anything about the Dyatlov group, but it helped me understand many nuances, which I will talk about below. Boris Sergeevich, for people interested in the Dyatlov Pass incident, the history of that time, your hiking diary is just a gift!

Please tell us about yourself. Who did you work for, what treks did you go on?

B.G.: The story of my life and work is very ordinary. Having graduated from the Faculty of Chemistry of Moscow State University in January 1959, I worked for two years at the Institute of Chemical Physics of the Academy of Sciences, and then moved to the academic Institute of Organic Chemistry, where I worked from April 12, 1961 (the day of Gagarin’s flight!) until my retirement in 2007 year. The social worker who processed my pension was very surprised by the small number of entries in my work book. My entire career growth fell within the boundaries of junior to senior researcher, which I do not regret at all, since, unfortunately, I am almost completely devoid of ambition.

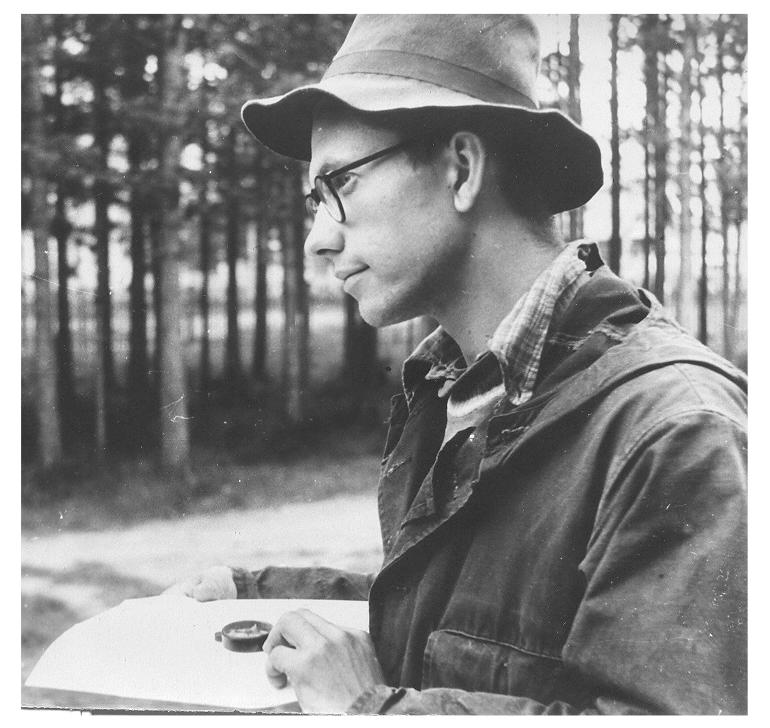

'I am curious to look at my 20-year-old self. This, however, is a "staged" photo taken at the end of the hike, in the city of Ukhta.'

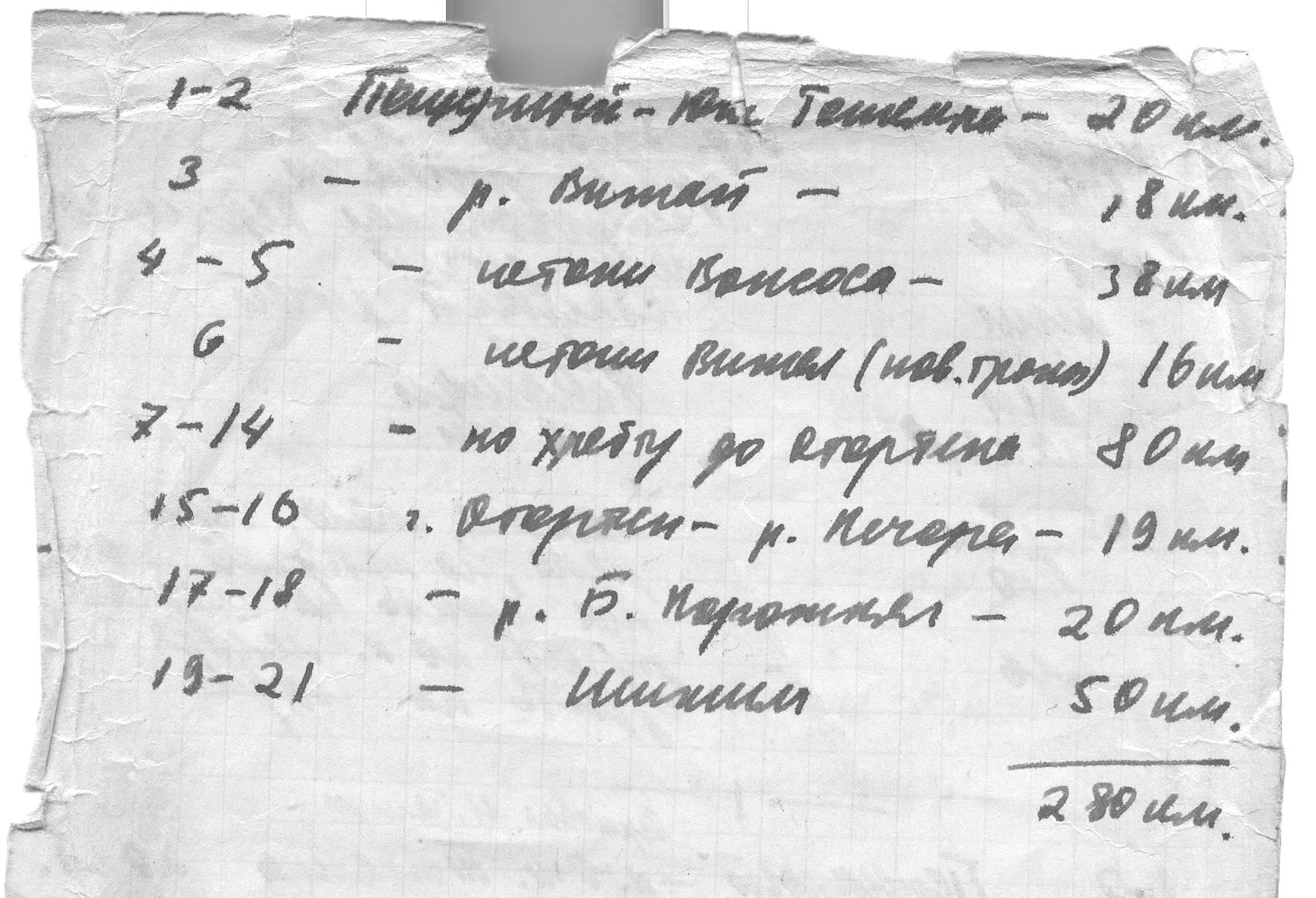

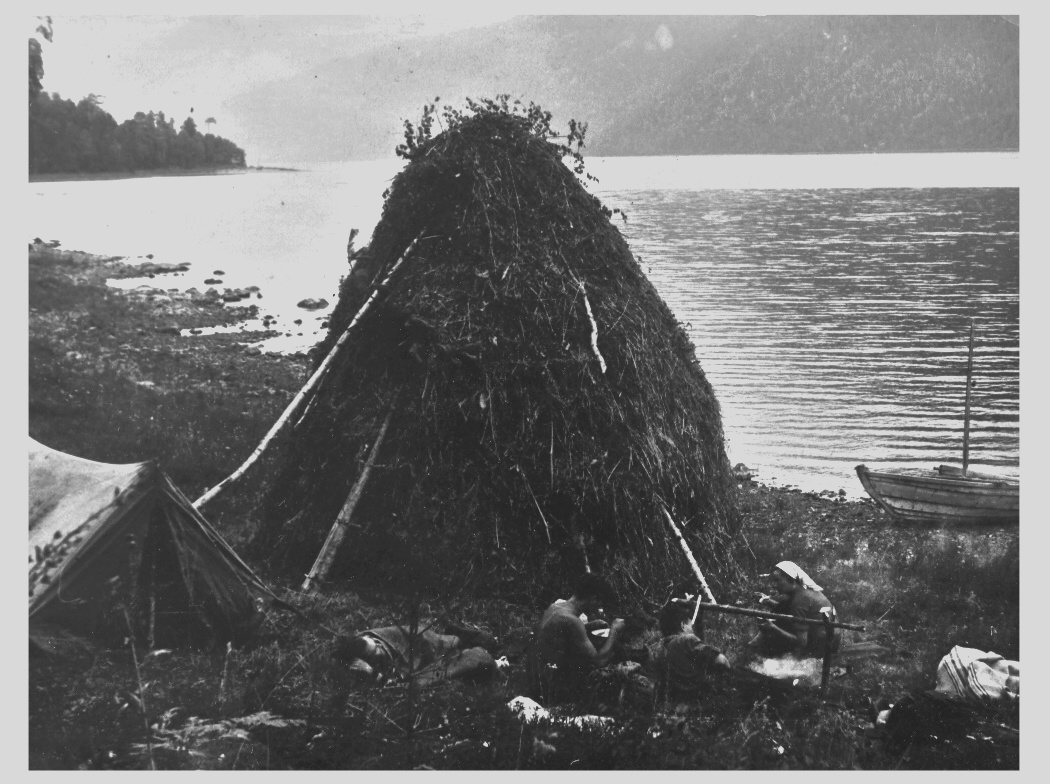

Besides the North Ural, another serious hikes in which I had the opportunity to participate, as Altai in 1955 (from Chemal on the Biysk tract to Artybash, including a boat trip from end to end of Lake Teletskoye), a winter hike in 1956 in the Middle Urals, a kayak trip along the rivers of the Vologda and Arkhangelsk regions in 1957, a 1958 trip through the Caucasus (from Dombay through the Baksan Gorge at the foot of Elbrus and the Donguz-Orun pass to the Inguri trail). Yes, I also forgot the rather difficult winter hike along the Vetreniy Poyas (Windy Belt) in the Arkhangelsk region. That's probably all, the rest is minor stuff. Unfortunately, I don’t have any full notes from these trips, only photographs, a few maps and other minor "storage items". After graduating from university, my hiking career was practically over.

Oddly enough, in retirement there is always not enough time, especially since I do quite a lot of scientific editing - not only and not so much for income, but rather out of natural inclination.

- 2 -

M.P.: Boris Sergeevich, your life is interesting, just like the life of any person, moreover an intelligent and educated one, and it is interesting not only for scientific discoveries, achievements and titles, for me personally this means nothing. All titles and scientific activities do not cover real human qualities and properties of the soul. And you are especially interesting to us as a witness related to the mystery of the death of the Dyatlov group, even if indirectly, as an eyewitness of a bygone time that reflected in your diary, a piece of the history of our country.

B.G.: I would like to say a few words after reading all the materials that you sent me with your first letter. I felt that I was then a stupid, thoughtless puppy who understood nothing in the world around me. How little we knew, and most importantly, wanted to know, about the places we visited, about the people living there, about the history of these places! Although, it seems, they were preparing for the trip quite seriously. However, thoughts about the pointlessness of simply dragging backpacks from point A to point B arose in me a long time ago, towards the end of my hiking career.

You are doing a great job. And not only because you are trying to understand that long-standing mysterious story. One way or another, in your conversations with the people involved in it, the living history of my country is visible. I, of course, know a lot about it, but what always moves me more is not the general reasoning, but the specific testimony of specific people with their momentary life.

M.P.: Thank you for your kind words, Boris Sergeevich. You know, I receive a lot of letters from ordinary people with gratitude for the published materials; people are interested not only in the topic of the tragic death of the unfortunate group, but also in the history of the country, the history of those places and people who unwittingly became involved in the 'Great Ural Mystery'. And I myself am interested in learning new facts, meeting new people and their life stories.

B.G.: Dear Maya Leonidovna, you, of course, know that recently there has been a whole series of programs on our television about the tragedy of the Dyatlov group. Unfortunately, this story was turned into a rather superficial show with a fair amount of - apparently, to attract a "wide audience" - mysticism, talk about the secrets of the KGB, aliens, Bigfoot etc. Malakhov's program was especially to blame about this. I don’t understand why the organizers didn't use your more interesting sources. I confess that I haven’t read all of them yet, but most of all I liked what Vladimir Askinadzi said and how he said it. I liked the sobriety of his assessments, rational skepticism, and reluctance to put forward spectacular hypotheses, which many participants in the mentioned programs were so susceptible to. This is the path that needs to be taken.

A lot of outright nonsense was said in Malakhov's program. They said, for example, that Dyatlov could not have maps of those places, that he wanted to be the first conqueror of Otorten, that he managed to get there only due to an oversight of the authorities, that then "being the leader of a hiking group he was obliged to write reports for the relevant authorities", that Otorten is in area of mysterious anomalous phenomena that the Mansi especially protect these places. I testify that when we went on a hike to the upper reaches of the Pechora river in the summer of 1956, two and a half years before the tragedy of the Dyatlov group, we had quite good detailed maps, received and re-photographed by us at the Faculty of Geography of Moscow State University (they are kept in my possession now), that in no way we did not have to contact any authorities other than the city Route Commission, that I never wrote any reports to the "relevant authorities", and it never even occurred to me, and we did not encounter any mysterious anomalous phenomena there. There were difficulties, but of a completely different kind. By the way, I learned that we, it turns out, visited the very places where the Dyatlov group died only from Tatyana Vladimirovna’s letter and from television programs, although at one time we talked a lot about the very mysterious death of the Sverdlovsk hikers, despite the complete lack of information about the incident in the press.

M.P.: Of course, I heard about the series of these programs, but I haven’t watched them in full until now. I was invited to participate in the program, the editor offered to arrange a teleconference with Spain, but I decided to refuse because I knew that nothing good would come of it. Sober voices are unlikely to be heard; the ratings of programs and the channel itself require exotic versions, the most scandalous assumptions, unsupported by documents and facts. It was psychics and the authors of such versions who were given the main say. I would like to note that all the news in 'Dyatlov case', new research on this topic now appears first of all on the Internet, and then television programs are made based on these materials, sometimes with a delay of a year or even more.

You know, there was so much speculation and discussion about the note from your group. For example, that there was no note, Muscovites were never there. And when the entire Dyatlov case was recently published, along with this note, new assumptions arose that this note was a fake and was not written by Muscovites. Tanya took up the matter decisively and wrote to you. I myself did a lot of searching for people on the topic of the death of the Dyatlov group, I know how difficult and troublesome it is to find a witness and get him to tell something, even just a little, and when Tanya said that she had found you, I was simply delighted and especially because you kindly agreed to talk about your trek! Believe me, knowledgeable people will appreciate it, and from the bottom of their hearts they will thank you both for the diary and for your recollections.

B.G.: I was very surprised that there was so much talk about our note on Otorten, especially about its forgery.

- 3 -

This note is genuine, we actually made a hike to the upper reaches of the Pechora in 1956, although I personally did not climb Otorten then for some reason. I did not write the note, and the signature on it is not mine. I don’t remember why the guys wrote it on my behalf. They probably thought that it should come from the leader of the campaign. However, this ascent in the summer was not at all difficult. The hike itself turned out to be very difficult and very memorable for me, for all of us. Unfortunately, I don’t know the fates of all my friends, some are no longer alive, and your letter brought back many memories in my soul.

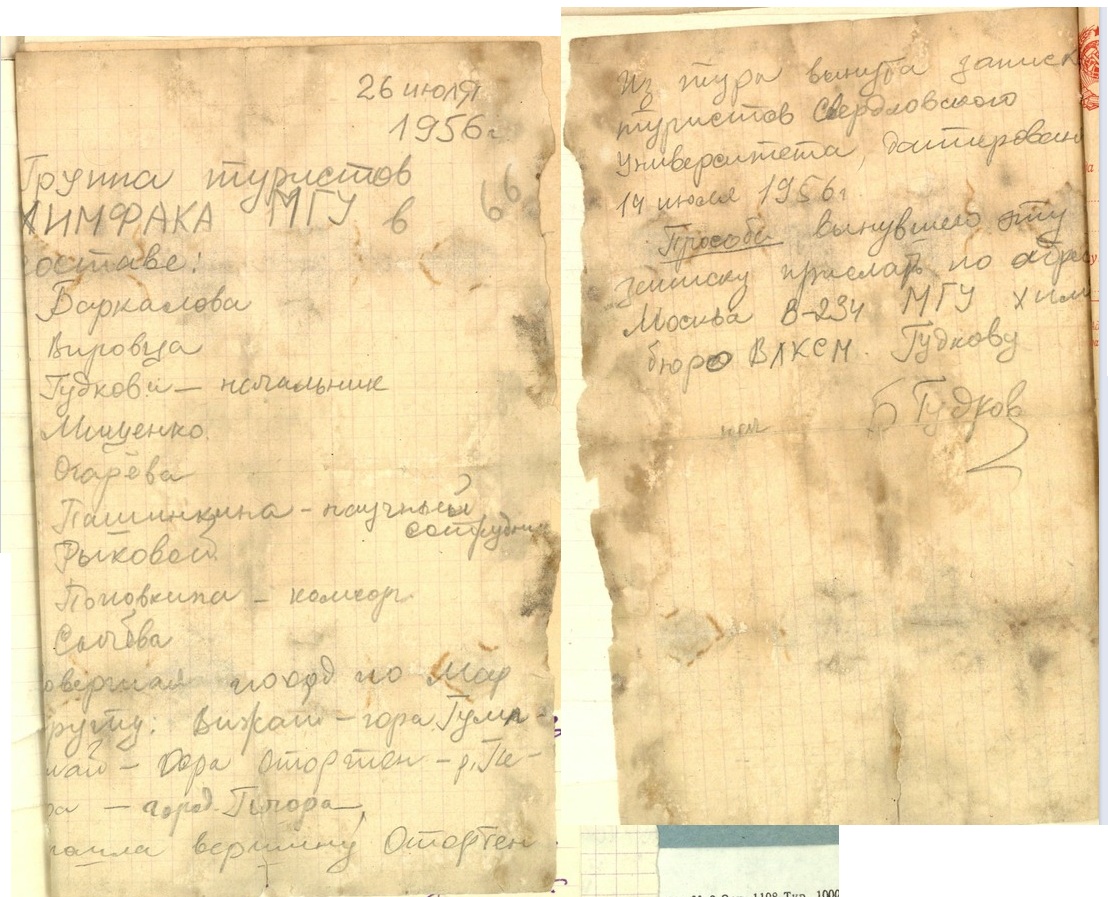

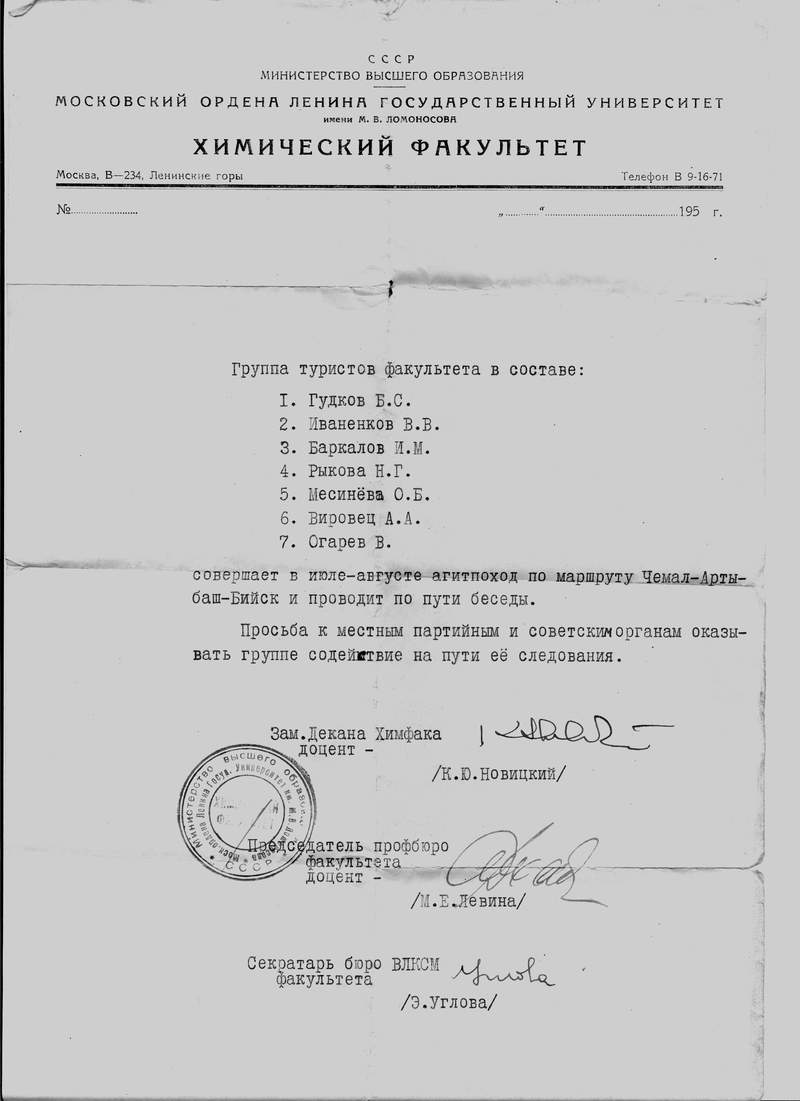

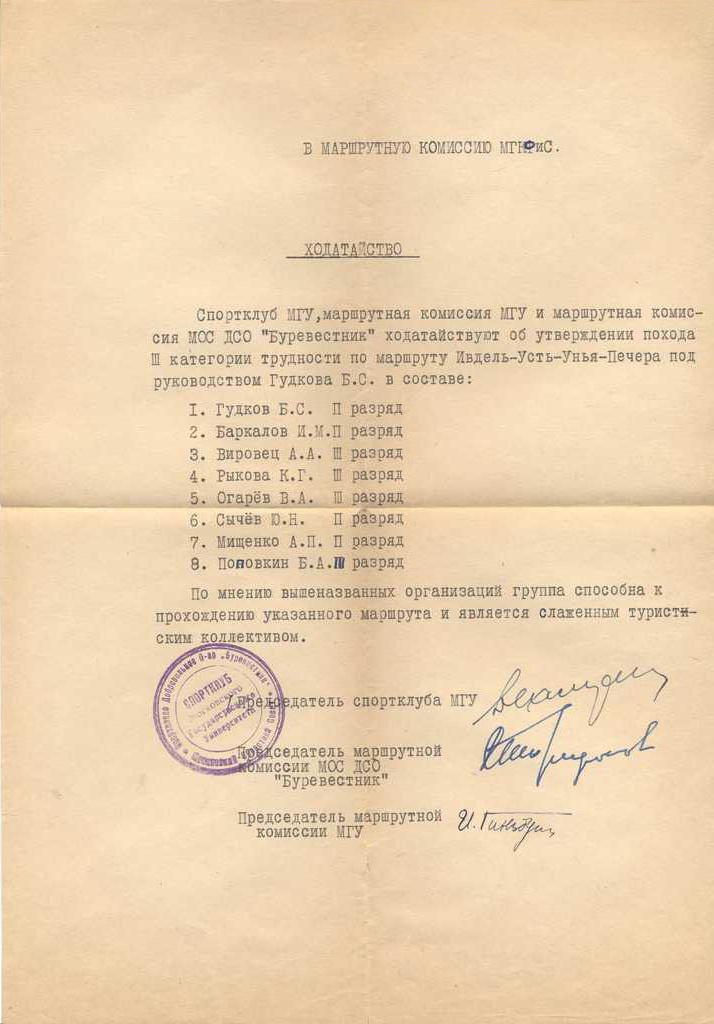

Petition to the city route commission. |

My diary will in no way help you in your research, but it can give an idea of the spirit of sports tourism at that time, of the relationships inside the hiking group, which were unlikely to be much different in Dyatlov's group. I am also enclosing our petition to the city route commission. For some reason, the last name of one of our members, Andrey Pashinkin, is missing from the group list. So in fact, there were not eight, but nine of us, and the number 9, as sacramental and dangerous, was mentioned more than once in Malakhov’s program on Channel One.

M.P.: A very interesting fact, Boris Sergeevich, that your group also consisted of 9 people. And everyone came back safe and healthy from that trip. This is just an aspen stake in the heart of the version of all lovers of the occult and the number 9!

Your diary indicated that your group took another note from Otorten, students of Sverdlovsk University, who climbed Otorten two weeks before you. Do you remember how many people were listed there, and what was written in the note? Maybe you still have it, or it was sent to the address indicated there?

B.G.: The question about the note from the Sverdlovsk group on Otorten also torments me. I kept trying to remember what we did with it. In all conscience we should, of course, have sent it to them or, at worst, transferred it to the Moscow Sports Tourism Council, but nothing emerged from the fog of my memory. I don’t even remember the text of the note, but it contained what is usually written in such cases: the list of the participants, their affiliation, the date.

M.P.: God willing, we will find members of that group. They were probably the first students to climb Otorten. Or maybe not, and they also took someone’s note from the top. One of them may respond.

Boris Sergeevich, why Otorten? Why did it attract you so much? Vladimir Askinadzi says that the route is not interesting. As I understand it, there is nothing interesting if you go from Vizhay to Kholat Syakhl along Lozva and then Auspiya, it's really long and boring, and everybody goes along this route just to repeat the path of the Dyatlov group. Why were you so drawn from Moscow to Otorten? How did you find out about it? How did you plan the route, did you conquer all the peaks that you had planned?

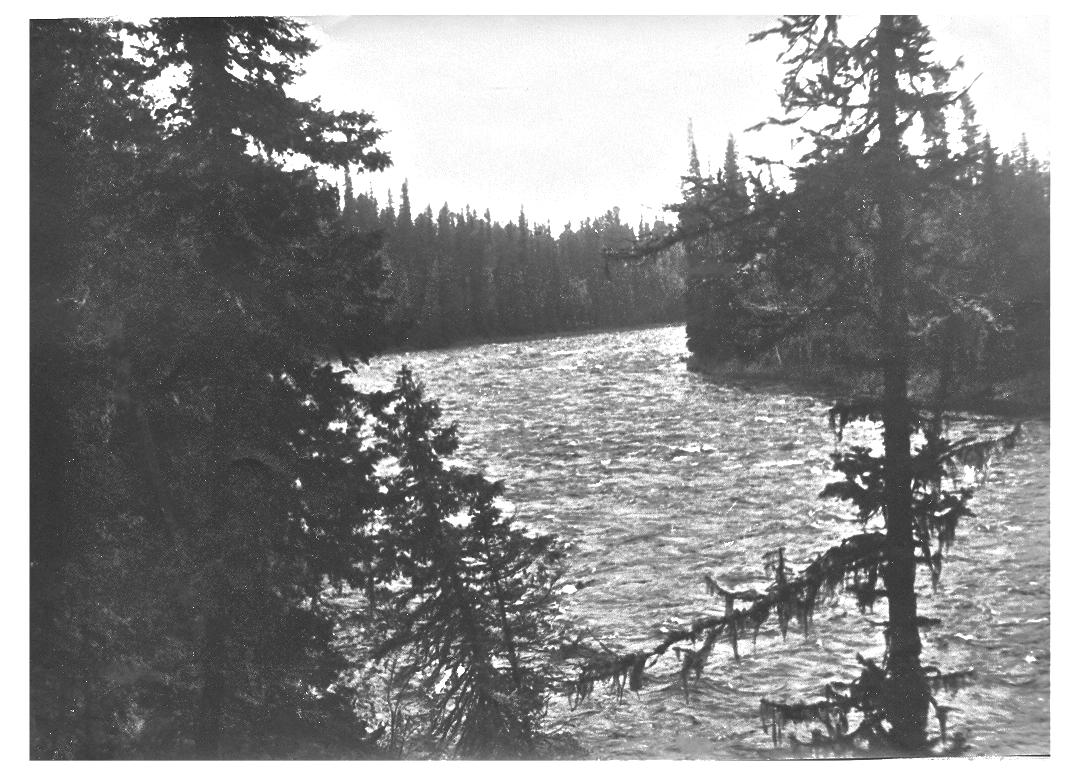

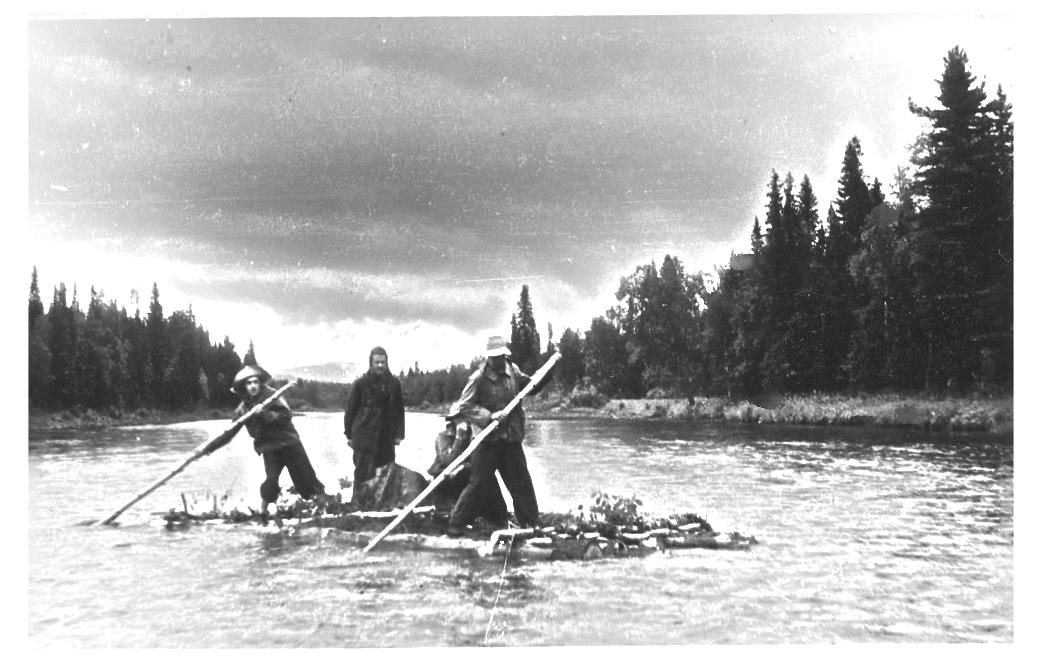

B.G.: Why Otorten? Yes, it just somehow happened that way. Otorten was not the goal of our hike. I don’t know if we talked about it at all before starting the trek. It was just one of the points on our route, and we were driven, rather, by the romantic idea of moving from Asia to Europe, rafting along the Pechora river from its headwaters, visiting places where no other group had gone before. In fact, it turned out that at least one group was literally two weeks ahead of us. We didn’t plan to "conquer the peaks" at all, and not all members of my group climbed Otorten.

- 4 -

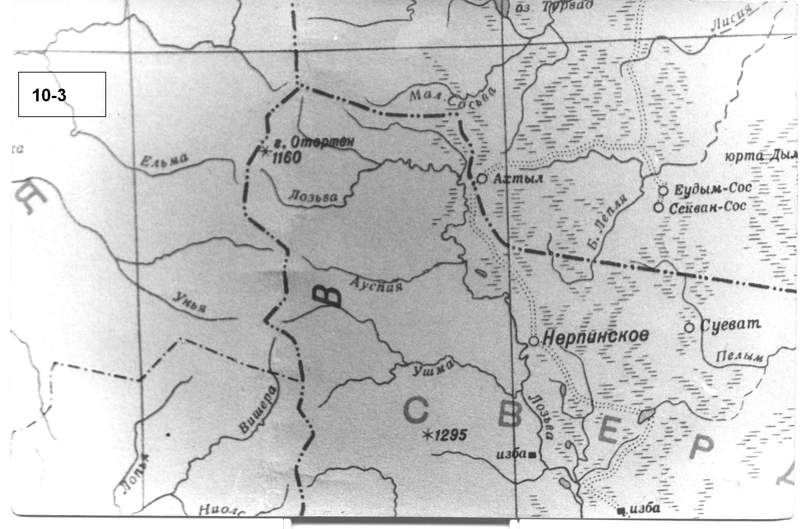

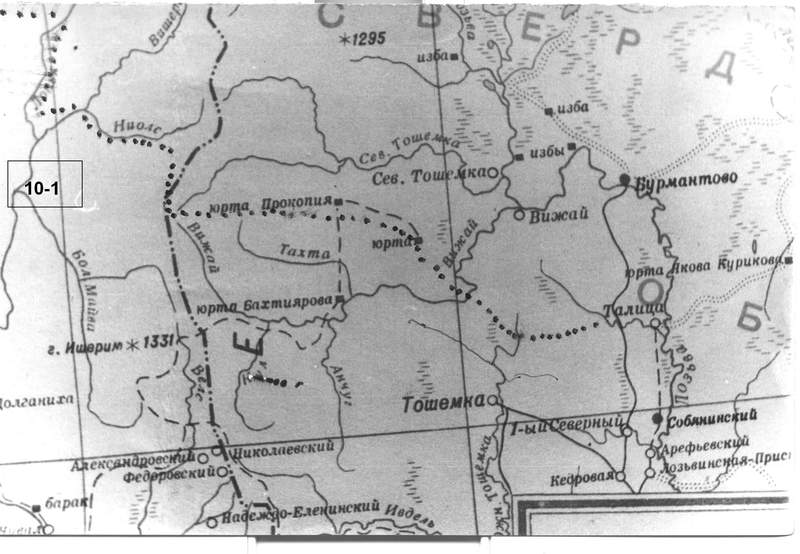

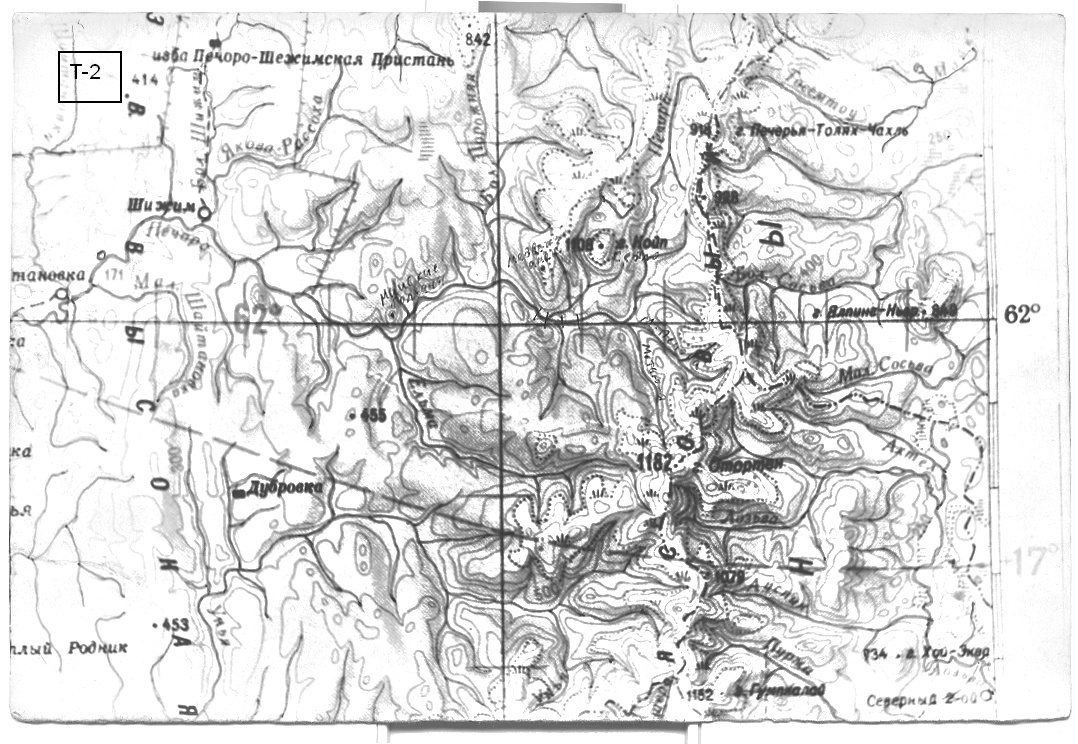

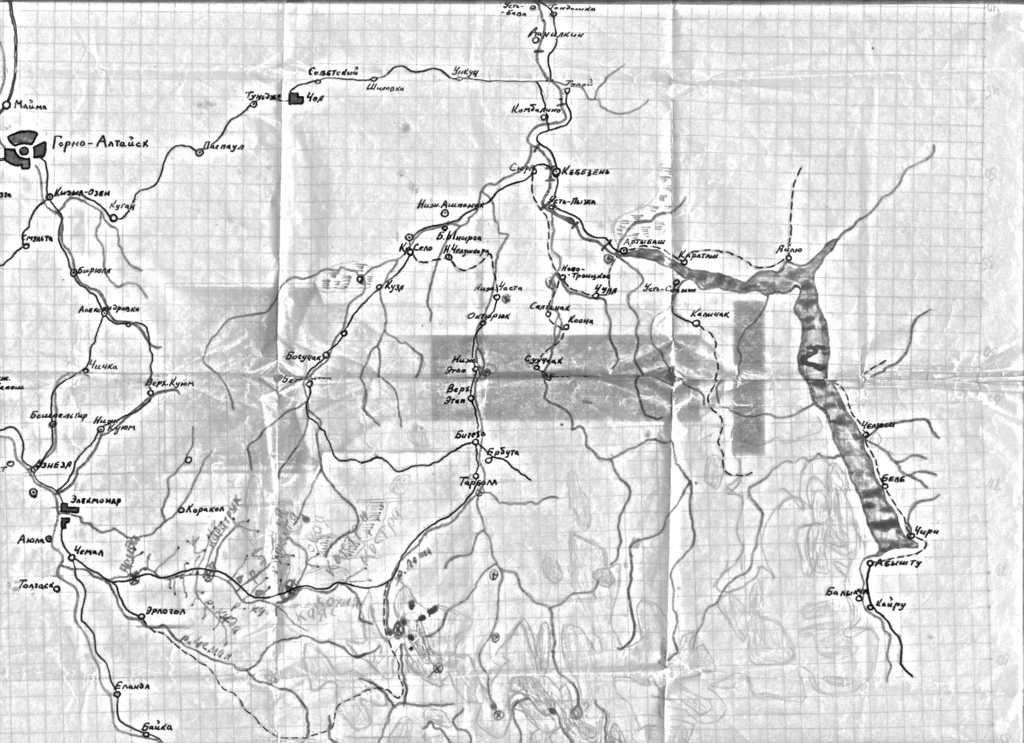

Back in January, conversations began with experts in the Northern Urals, trips to the TEU (tourist and excursion management at the Ilyich Outpost), where reports of all previous trips were kept. As a result, we had in our hands a million-scale hypsometric map (10 km scale map), a five-kilometer map and a ten-kilometer map of the Pechora River. The best and only map we used was the hypsometric chart. Without the map it would be difficult, if not impossible, for us to go. In general, it must be said that maps without indicating the heights in the area of our hike are absolutely useless, since the peaks were one of the most important landmarks for us. From reports and conversations with experts, we found out that they can tell something about the first part of the route (to the ridge), and even further in a slightly more southern area. From guidebooks and Hoffmann’s very detailed and explanatory book (travel reports of 1849, 1851 and 1856), we got an idea of the character of the upper Pechora and its tributaries. The most serious and responsible part of the trek - the ridge - remained for us, in fact, a blank spot. We only knew that the ridge tops in this area were treeless.

You need to keep in mind that we took pictures of the map with a camera in parts, so the frames are separate and partially overlap each other. And the real scale is not 1:1,000,000 or 1:750,000, but somewhat different (it is naturally distorted during photo enlargement, and probably during scanning), but this doesn't matter, because you cannot walk on these maps. Two circumstances are noteworthy. Firstly, the different maps do not completely coincide with each other, which, of course, did not make our life easier. Secondly, most of the settlements marked on the maps did not actually exist at the time of our hike. In any case, along our entire route after the camps and Nikolay's hut, right up to Shizhim on Pechora, we did not encounter a single village or simply a separate inhabited dwelling. On the 7.5 km scale maps there is a dotted line, which apparently marks our path, but I don’t remember whether this was done before the start of the hike or after. Now I wouldn’t undertake to pinpoint our route exactly.

M.P.: Thank you for the maps! I will place all the photographs and maps that you sent on my Yandex page, in a special album. Again, to confirm, there were no such names on the map as Kholat Syakhl, much less the Mountains of the Dead; all this was invented in our time, when it became possible to talk about the tragedy. It was just height 1079. I wonder how you defined was the transition from Europe to Asia was, were there any signs there?

- 5 -

B.G.: There were, of course, no signs "Europe - Asia" in these wild places and, I believe, there are not even now. But when you stand on the Ural ridge, which is not so wide, about a hundred meters, there are no doubts of the sort. And we received all these maps and re-photographed them on the spot in daylight, on the windowsill at the Faculty of Geography of Moscow State University.

M.P.: Boris Sergeevich, from the entries in your hiking diary on Otorten, I noted the following moment: you tried to lit a fire and for a long time could not light it, until, finally, you used a piece of photographic film. Was it new film or defective? What was the situation with photographic films for hiking at that time? Was there a shortage? They say they even used film cut into pieces like photographic film? Did you carry photographic film specifically to start a fire in difficult conditions, or did you use new, undeveloped film?

B.G.: Ordinary photographic film was not at all in short supply at that time, unlike other photographic materials, for example, some types of photographic paper. But, in general, after running around Moscow stores, you could always find what you needed. Quality is another matter; there have always been problems with this. Now, of course, I don’t remember what kind of film we used to light the fire. Most likely, we had some surplus. By the way, during our hike along the Vetreniy Poyas (Windy Belt) we managed to get a truly unique, highly sensitive photographic film that made it possible to take pictures even by the light of a fire. Some acquaintances at NIKFI (film and photo institute) helped.

M.P.: Thank you, now it’s clear that there were no problems with photographic film in Moscow. Probably not in Sverdovsk either, although who knows, Krivonischenko from Chelyabinsk-40 wrote that he had problems with photographic film and asked if it was possible to get film in Sverdlovsk. A piece of film was found among the Dyatlov group, found 15 meters from the tent; the witness said that this roll of film rolled out of the tent as a result of an inspection of the tent the day before. What kind of roll it is, how many meters it is, is unknown. It turns out that it was overexposed. Witnesses say that at that time film was also used for photography.

B.G.: Cutting film into pieces and rewinding them onto photo cassettes would be much more convenient to do at home. It is unlikely that the Dyatlov group would be able to load the already cut pieces into the case; this is an extra opportunity to expose the film. Has it ever occurred to anyone to compare the film from the Dyatlov group cameras with the film from the roll?

M.P.: The investigation may have made comparisons. The fate of some of the films and this roll of film is unknown. With photographic films you get an interesting picture. They suddenly turn up in the personal archive of investigator Lev Ivanov, although according to the law they should have been confiscated from the place of inspection where they were at the time of discovery, and a seizure report should have been drawn up. Then all the negatives had to be packed in a special envelope, which was numbered and filed with the case file. After all, the films could contain some evidence, this is material evidence. People died. No one knows why they died; at the site where the tent was found, they found cameras with films and films in an sealed tin can. The killer may be captured on them. Or the moment that caused the death of the group? In any case, photographic films are the most valuable physical evidence and must be formalized according to the law so that they can later serve as full-fledged evidence in court. In fact, films are found in the possession of investigators in our time. Moreover, according to the daughter of investigator Ivanov, Alexandra Lvovna, these films were ordered to be destroyed, but Ivanov kept them in his archive, hiding them in a safe place, so much so that they could not be found immediately after his death. So, thanks to investigator Ivanov, we can see trek photographs of the Dyatlov group. Who developed these films in the forensic laboratory of Sverdlovsk, who saw them first, who cut out, perhaps, dangerous frames, leaving only insignificant ones, in their opinion, we do not know. We have what we have. Thanks to investigator Lev Ivanov, who acted against the orders.

M.P.: Boris Sergeevich, you noted in your diary that two comrades did not listen to the leader of the trek and went about on their own, about their own affairs. Was this encouraged? In your personal experience of camp life, were there often such cases when the group disobeyed the leader and even split into parts? As far as I know, sometimes such cases ended tragically.

B.G.: In general, from the very beginning, even before the election of the leader, there was an agreement that after any discussions, the final word always belongs to the leader of the trek, no matter who he is, this is the law. It wasn't even discussed. In fact, I would characterize the "political system" in the group, at least in ours, not as autocracy, but as enlightened absolutism. Still, both the boss and the members of the group were all their own guys, and the boss did not appear from somewhere above, but was elected from among his own (in particular, this troublesome duty was assigned to me, it seems to me, mainly because I did not know how to refuse). We could argue, discuss, disagree with each other, but only until the final word from the boss. Everyone initially understood that this was necessary for the safety of the group and the consequences of disobedience could be the most severe. I, unsurprisingly, have no living memory of that sad episode, but apparently the offenders were subjected to "the harsh judgment of their comrades" and no more similar cases seem to be noted in the diary.

- 6 -

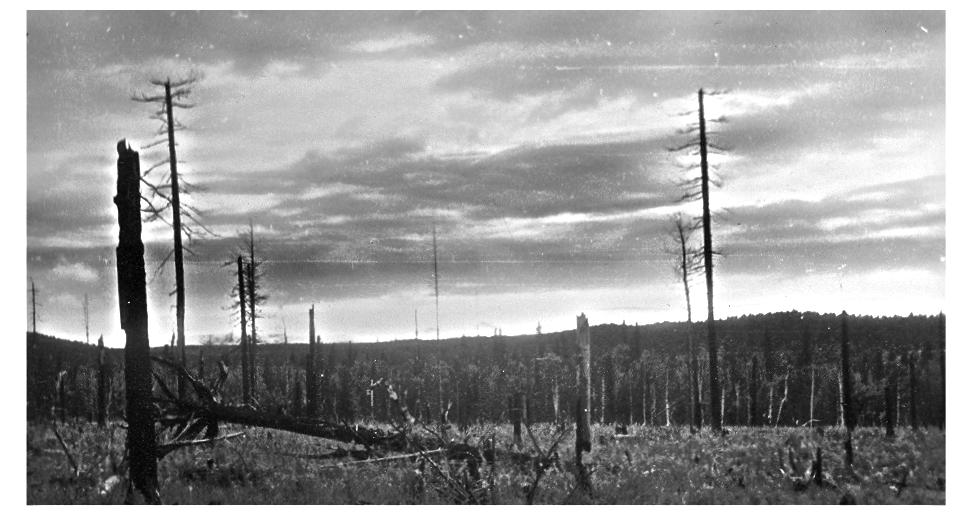

M.P.: The group's diary you noted that on the way to Vizhay, "the pictures all around are, in general, gloomy. Everywhere there are labor camps or traces of the activities of prisoners." Please explain this gloommy feeling. You wrote that when the group was at the 100th district, you had to be on duty with a gun all night. And different people came to your fire, which made your soul uneasy. Did the camp authorities warn you about the danger of those places, about the danger of contacts with the population, or did you yourself think that you were in the edge of the labor camps and therefore were afraid? Did anyone along the way tell you about prison escapes? Why did you decide not to shoot game until you left the camp area?

B.G.: The gloomy pictures on the way to Vizhay are, of course, towers and barbed wire, traces of activity - clear cuttings of forests.

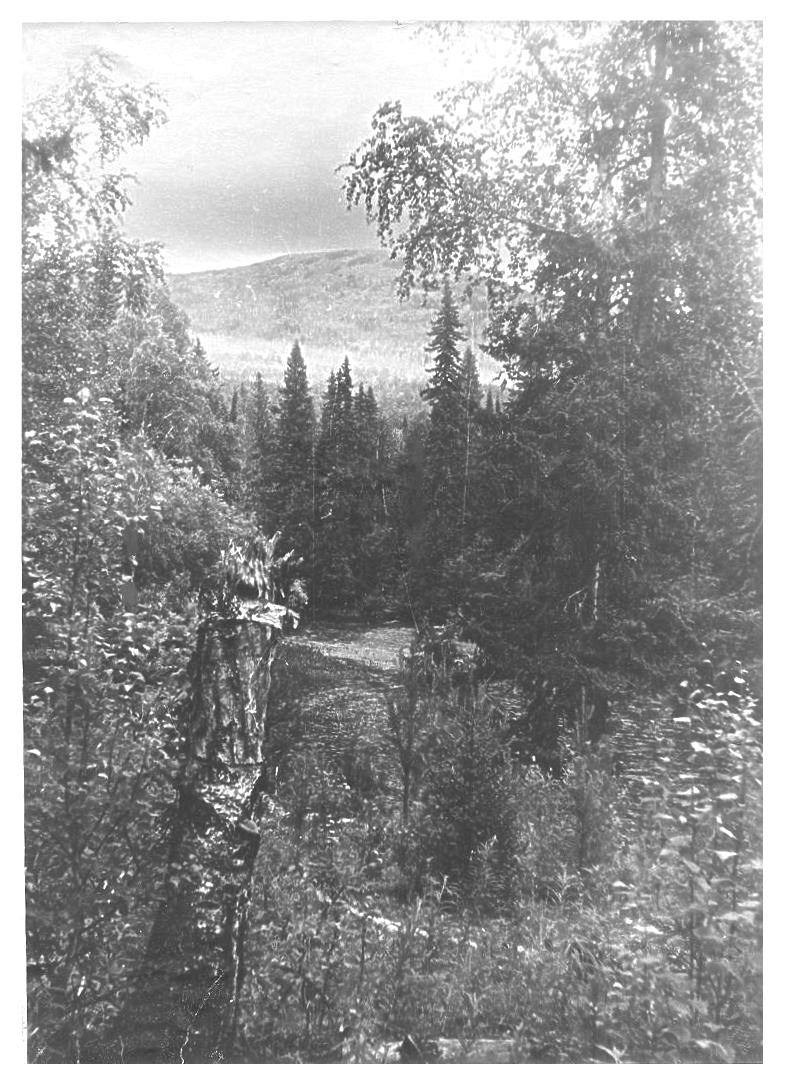

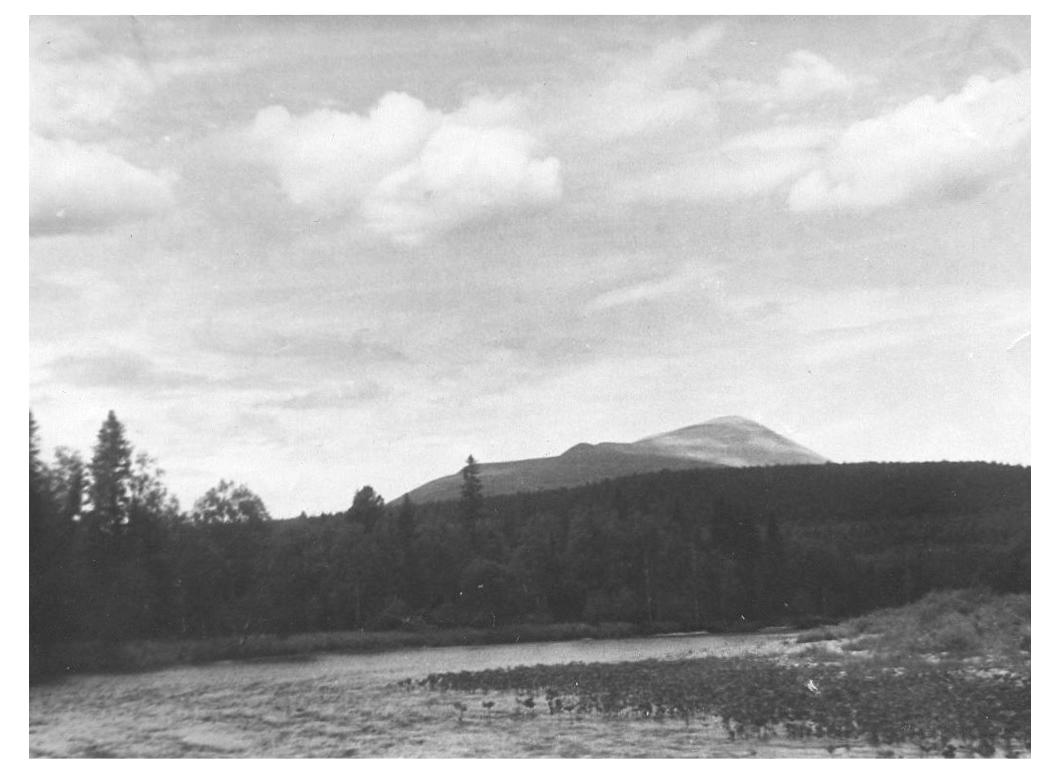

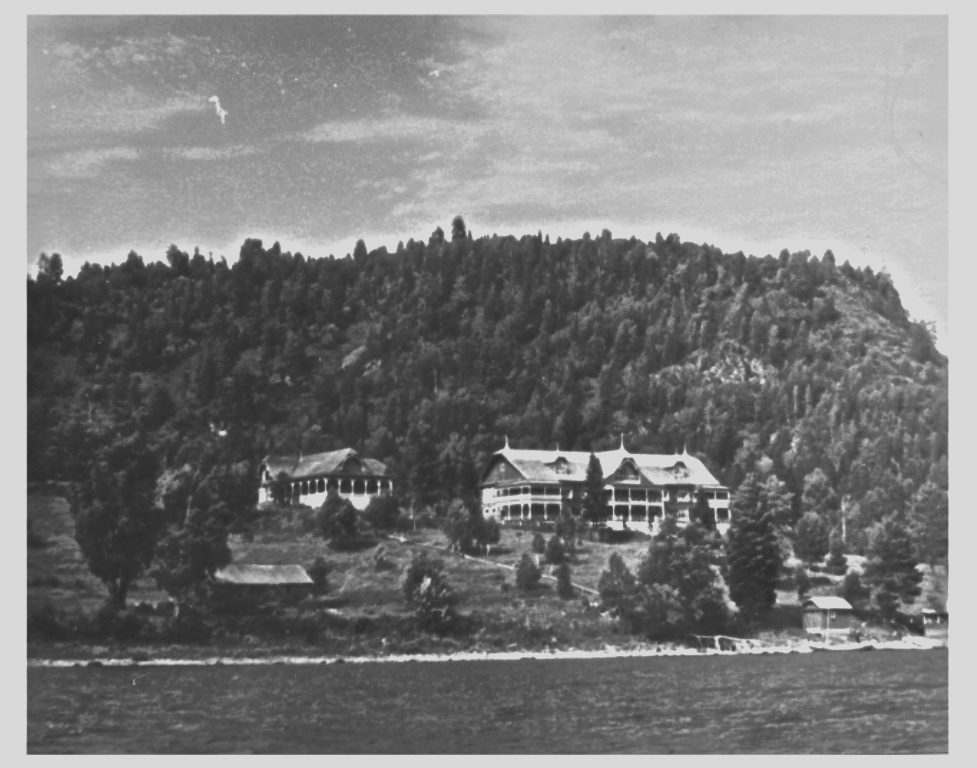

View of the Northern Urals along Gudkov group’s route

In those places (and we started from Vizhay) there were then many labor camps, and in the first days we were forced to stay in shifts at night with the only single-barreled hunting rifle we had. We heard that the local population (Mansi) received serious material incentives for helping to capture (was it only to capture?) fugitive prisoners. At that time, we vividly discussed the "camp" versions among ourselves. As you, of course, understand, it is difficult for me to remember all the details after 57 years, but it would be difficult not to experience disturbing sensations in the "zones" even without warnings from the authorities. That’s why we decided not to hunt in the first days, so as not to provoke the emergence of some undesirable situation with shots.

M.P.: I would like to clarify this question: when you were traveling to Vizhay, was your group stopped by inspection posts along the route and how many times? What were asked and noted? And when you arrived in Vizhay, were you supposed to report to the camp authorities and report the target dates for the hike? Do you remember the camp commander? Have you gone to the Vizhay forester to ask about the route?

B.G.: There were no checks from the "inspection posts" on the way to Vizhay. And in Vizhay itself (most likely, it was there) we, of course, had to make a mark with a seal in some official institution, just like at the end of the hike. This was a strict requirement of the route commission and generally a general rule. Unfortunately, I don’t remember where exactly we got the stamps. I don’t remember if we went to the head of the forced labor camp. Hardly. And we didn’t contact the forester. We tried to get out on the route as quickly as possible so as not to experience those same unpleasant sensations.

Lezhnevka Ivdel-Vizhay

Photo by Gennady Kusov, son of the head of the Vizhay labor camp, B.M. Kusov

M.P.: It turns out that posts, or zones, as they were also called, appeared on the road to Vizhay later than 1956. Local residents said that there was no checkpoint "on Vizhay"; they entered as usual, as into any village. And on the Ivdel-Vizhay road there were checkpoints, an operatives were on duty, they checked all the visitors, where, to whom, who was going. Well, in the village, hikers came into the "office", checked in, and notified the camp administration. They asked for help to get to a certain place, and they were assisted with this.

Boris Sergeevich, was it mandatory for each participant in the hike to have a passport? Or could you be content with a pass with a photo, or some other identification document? A library card, for example, with a photo? Did you sign up for a business trip for this hike and receive a travel certificate?

B.G.: Of course, we had passports with us, although I don’t remember any specific case when they were needed. However, no, I remembered: the money for the return journey was kept on our letter of credit, and it would have been impossible to receive it without a passport in Ukhta, from where we were leaving for Moscow. A passport was not required when purchasing train tickets then. It is quite possible that during the flight from the "Kurya airport" (you should have seen this airport!) to Troitsko-Pechersk they were not very interested in our passports. We were not issued any travel certificate, but there was a covering letter from the faculty asking for assistance. We showed it to the police at the station in Ukhta, when they woke us up, sleeping on our backpacks on the floor, and asked who we were. I don’t have this letter from the Ural trek, but I have a similar one from the Altai trek.

M.P.: Could this cover letter also be called a travel certificate? As I understand it, at that time you could easily travel without passports if you didn’t have letters of credit and carried all your cash with you. If anything, you could show a piece of paper from the institute and that’s it. Return tickets were not accepted then; there was no such system, as I understand it.

B.G.: I don’t know whether a cover letter can be called a travel certificate. Hardly. It is still necessary to make some official notes on travel certificates. We called it among ourselves a "safe conduct letter". As for passports, I’m afraid you didn’t understand me quite correctly. Do not forget that in 1956, only three years had passed since the death of the great leader of all peoples and the luminary of all sciences, and the fear of being found guilty without guilt in the face of the interested authorities had not yet evaporated. So it was necessary to have evidence of your loyalty with you. And when was it different in our country? Another thing is that ordinary people and lower management could see clearly who was in front of them, and they did not have to show their passport often. But you should have had it with you.

M.P.: Boris Sergeevich, how were the documents of the group members and money kept, with whom? Did everyone carry their passport with them, or did they give it to the leader? The general money was probably kept by the treasurer, or by the leader. Did you take personal money with you, or did you mainly use letters of credit?

B.G.: As far as I remember, everyone carried their passports in their own backpack, it was safer that way. In my opinion, there was no personal money, somehow it didn’t fit into the general system of relationships in the group, but there was, of course, some total amount in cash, and sometimes you had to pay on the spot (for example, for transportation by boat from Ust-Unya to Kurya or by plane from Kurya to Troitsko-Pechersk). I can’t say for sure who kept this money, maybe even me. The letter of credit could, of course, be used only where a savings bank existed, in our particular case - in Ukhta, and this money (the bulk of our funds) was intended for return tickets to Moscow.

M.P.: Rustem Slobodin’s passport was found in his breast pocket along with a certain amount of money. Didn’t all this get in the way during a hike when the straps of a heavy backpack chafed? After all, the passport could get wrinkled, and even dig into the body under such a load, it could get wet from sweat... What do you think? Have you personally or someone you know carried a passport in the breast pocket of a shirt or kacket on a hike?

- 8 -

B.G.: I’ll try to turn not so much to memory as to simple logic. Do not forget that the Dyatlov group walked in winter, and in these conditions it was quite natural to carry documents in their breast pockets. I don’t think the backpack straps, much less sweat, could have damaged them in any way. The straps of a properly assembled and packed backpack do not overlap the "chest pocket area", so to speak. It's a different matter in the summer. In the summer you often get caught in the rain; in the summer, the pocket of a shirt is usually not protected by the material of a windbreaker or sweater; in the summer, sweat sometimes pours out. It makes more sense, of course, to carry documents in the backpack, in some kind of waterproof container. There were no plastic bags in use in our times, and we most likely made do with oilcloth for this, as well as for storing matches. But this is not information from memory, but again simple logic. I don’t remember where or how I carried my passport. I think, depending on the circumstances, whatever was more appropriate.

M.P.: At the beginning of the route you noted the following episode: "In the evening the Sverdlovsk-Polunochnoe train dragged us further. Early in the morning we arrived in Serov. Here the cars heading to Polunochnoe stood the whole day: for some reasons traffic on this section is carried out only at night." Why at night, for what reasons?

B.G.: I am forced to refer to memory flaws that prevent me from answering the question about the reasons for the delay in Serov. It may not have been desirable for passengers to see too much on the way to Polunochnoe.

M.P.: I was struck by the entry in your hiking diary about the Mansi sites that your group encountered along the way. That there were empty bottles lying among the fire pits. In one of the photos of the Dyatlov group’s search, you can see a fire pit, charred trunks and some kind of bottle in the snow near the firelog.

Is this a bottle by the Cedar? |

Yuri Yudin puzzled over this photo about where the bottle came from. I considered this bottle to be important evidence of the presence of outsiders. Other researchers decided that it was not a bottle, but just a twig or fire log. Or the bottle was left behind by the searchers. I kept wondering why this photo of the remains of the fire pit and the bottle was taken, with investigator Ivanov himself standing in the background. The searchers couldn’t bring a bottle, drink it where they found two corpses near an extinguished fire, and then take a photo of the abandoned empty bottle against the backdrop of a fire log. I saw the answer in your diary - there were Mansi there! The fact that the Mansi had a resting spot near the Cedar is also confirmed by former searcher Valentin Yakimenko, and journalist Gennadiy Grigoriev, who also took part in the first days of the search, even dug up some skin in the snow near the Cedar, though now, he no longer remembers this episode, but the note about the skin remains in his notebooks. The skin was probably deerskin.

I asked Valentin Yakimenko if they had encountered traces of the Mansi in that place, the answer was affirmative. They found Mansi items in the area of the pass, near the outlier and on the slope of Otorten. These were out of use and therefore abandoned Mansi items. Vladimir Askinadzi noticed that the fire near the Cedar could only be called a fire "in quotation marks"; it was a slightly burnt birch trunk, a rotten tree that could not warm up in the cold. One inevitably comes to the conclusion that it was not the Dyatlov group who lit that fire, but that it was an old Mansi camp near a cedar tree, with the remains of a fire pit and an abandoned vodka bottle. Near this Mansi site, the burnt bodies of the Dyatlov group were placed by someone. With the den, it’s not so simple either. There was a trail from fresh spruce branches to the ravine. And the den itself, as can be seen from the photo, was mainly made of old crumbling fir branches, with smooth cut edges, and it was build in a place where, according to local hunters, it was possible to track wood grouse. As if someone wanted to lead the investigation to the trace of Mansi’s involvement in the death of the group.

I was also impressed by your message in your diary that at the top of height 1079 the group discovered a Mansi sacrificial sign with a bear skull. But the Mansi, all as one, said that the mountain is not considered sacred and is not visited.

B.G.: Unfortunately, I don’t have a photograph of the bear skull. As far as I remember, there were no poles there, and we didn’t look at how the bear’s skull was secured, because we didn’t come close to it, much less touch it with our hands. Out of respect for local shrines. I remember that we encountered similar signs in other places on the ridge, perhaps on Otorten. And the Mansi could well have left the bottle. As it was clear from a conversation with Mansi Nikolay, who accompanied us for a couple of kilometers at the very beginning of the hike, the topic of alcohol interested him very much. But on the ridge we often came across "Mansi" bottles.

Yudin seemed to me, including from your interview, a very modest and very decent person. Rest in peace! Alas, our generation is leaving, and this is happening very quickly...

- 9 -

M.P.: For me personally, it was important to finally resolve the question: where did the empty bottle come from there, by the fire? You have an entry in your diary that the same Nikolay, who is Mansi, kept asking you about where he can buy alcohol. "All the way he chatted incessantly, wondering mainly whether there was vodka in Vizhay, 1st Northern and other places...”

B.G.: I have to admit that I was too little interested in local people and everyday life in the places I visited.

M.P.: Another very interesting moment noted in the diary is that your group saw a silver plane suddenly appear from somewhere, which began circling above you when the group reached the western slope of height 1079. You even saw that it has two motors. For some reason you assumed that aerial photography was being carried out. I asked one former Ivdel pilot what kind of plane could have flown there, was it an aerial photograph? He said that the best aircraft for aerial photography at that time was the Il-14, which had an autopilot and automatic program turn. Judging by your diary entry, it could have been an Il-14 or Li-2 aircraft, since there were two engines and the aircraft was silver in color.

Ilyushin IL-14M. Photo by Rodion Nikolyan |

Lisunov Li-2 |

Aerial photography could well have been carried out from both aircraft; at that time, a lot of this work was carried out to create and update topographic maps. IL-14 could stay in the air for up to 9 hours. His only remark is this: the survey is carried out on parallel tacks, usually from west to east and back. And the diary said that the plane was circling over the group. This is more like search work, when the plane, having arrived at an object of interest, spins a spiral, expanding the search. Or maybe your group was being monitored.

An interesting point was that the plane suddenly appeared when you found yourself on the top of Kholat Syakhl, circled above you for two days, and suddenly disappeared when your group left the vicinity of Kholat Syakhl.

B.G.: The two engines of the circling plane were clearly visible. But I’m not sure whether he was circling above us. It probably had some other goal. Why did we think about aerial photography? What else could come to our minds? This was the most natural explanation. We, of course, did not know the rules of aerial photography.

M.P.: I read a very interesting passage on the topic of tragedy, which also echoes your expedition to Otorten. This applies to the very planes that circled above you for two days in a row while you were in the area of height 1079. The son of one of the witnesses in the Dyatlov group’s case, Lev Gordo, wrote: "My father turned to the pilots from the Uktus airport for help. They shook their heads and said right away that the area where the group disappeared was inaccessible for flights. Perhaps nuclear warheads were stored in those places at that time. I would like to add that there are such "bans" even in the Moscow region. The territory is fenced with barbed wire, and if you go further, you can see the inscription: "Forbidden zone - shooting without warning". As a result, the pilots said that they could not fly into these squares and they needed permission from the KGB. The father was between a rock and a hard place. On the one hand, the guys’ relatives demanded news. On another - there were KGB officers who strictly forbade the dissemination of any information about the Dyatlov group. A KGB officer boarded the plane to search. He immediately said that there was no need to send the guys to certain death. The Dyatlov group ended up in forbidden areas and, in fact, became state criminals. The places they wandered into were never visited by anyone. Who killed them is the second question and not so important. They became criminals - they were destroyed."

Did you ask anyone for permission to go to those places? That’s interesting, you probably went without any permits. And planes were circling above you....

Didn’t the relevant organizations control local sports tourist clubs? Didn’t they keep track of where the hikers were sent, to what areas? After all, in our country there has almost always been total control over everything and everyone...

B.G.: We really did not receive any permission to travel along our route, and it never even occurred to us to ask for such a thing, since our route lay very far from the border areas. And we didn’t attach much importance to airplanes, it was just nice to see evidence of civilization in wild places. You are absolutely right about total control, and that is why I think that all the talk about secret restricted areas in the Otorten area is complete nonsense. No matter how you feel about the activities of the "authorities", they still received some kind of professional training, and they probably could have prevented the appearance of unnecessary people in an unnecessary place without bloody incidents.

- 10 -

B.G.: The idea of storing nuclear warheads in those places seems quite ridiculous to me. To bring them there, and most importantly, to quickly take them out if necessary, you need at least reliable roads or at least a good airfield. You know much more about those parts than I do. Have you heard of anything like this? The Moscow region is a completely different matter. And who said "no one has ever walked in these places"? We went! Not counting the locals, in 1956 alone, as you know, at least two hiking groups trekked there.

M.P.: I asked the same Ivdel pilot whether it was true that in the Ivdel region there were squares into which it was forbidden to fly without KGB permission. And how will he comment on the story of Lev Gordo's son.

Here is his answer: 'Each flight is carried out strictly along the routes, and then the day before a preliminary flight plan is submitted for approval and obtaining permission. There were and still are forbidden and semi-forbidden regime zones. We knew many such areas where anti-aircraft firing training was carried out, or in the south they were shooting at thunderclouds. All of Moscow is a restricted area unless you fly along designated corridors. There was a complete ban on spaceports, military training grounds, and sensitive factories. Restricted over hydroelectric power stations and nuclear power plants. There were flights over the Chernobyl nuclear power plant and in the area of Zvartnots Erevan airport. KGB officers supervised the work of air traffic controllers when a special flight regime was established in their area of responsibility. And there really was order.

Military units, fenced with barbed wire, were everywhere, but these were, as a rule, units and towns with a developed network of access roads. It made no sense to store nuclear warheads, of which we clearly had few at that time in 1959, away from the launch pads. But getting all the construction facilities and intercontinental missiles there, having no roads, could only be done by helicopters, and even if observing the secrecy regime, it would hardly have been possible. I think there were no nuclear warheads there.

The KGB officer may have been in the search group, but he probably did not speak out so cynically. And hunters, geologists, and even hikers walked freely through those taiga places.'

M.P.: Boris Sergeevich, you describe very interesting details in your travel diary. On the slope of Otorten: "We walked all the time along Motya and soon came across a real road with many traces, not marked on our map. The road crossed the river valley and went east, to the ridge. Here the real taiga began, already familiar to us, and in Looking for an easier path, we climbed up."

Do you remember what kind of road it was? For some reason, all these unknown roads, unmarked on maps, and mysterious planes in that area, and even the periodic shaking of Mt Kholat Syakhl at that time, are very alarming to me.

B.G.: Memory is an unreliable thing, mine at least, and I don’t remember that road at all. I don’t think it was a somehow equipped route. I looked at the map again and still found the Motya River. This name is written by hand and is very hard to see, but if you look at the hypsometric map, you can see a stream flowing straight from the height with mark 1182 (Otorten) to the north (i.e. up) in the direction of Mount Koyp (1108) .

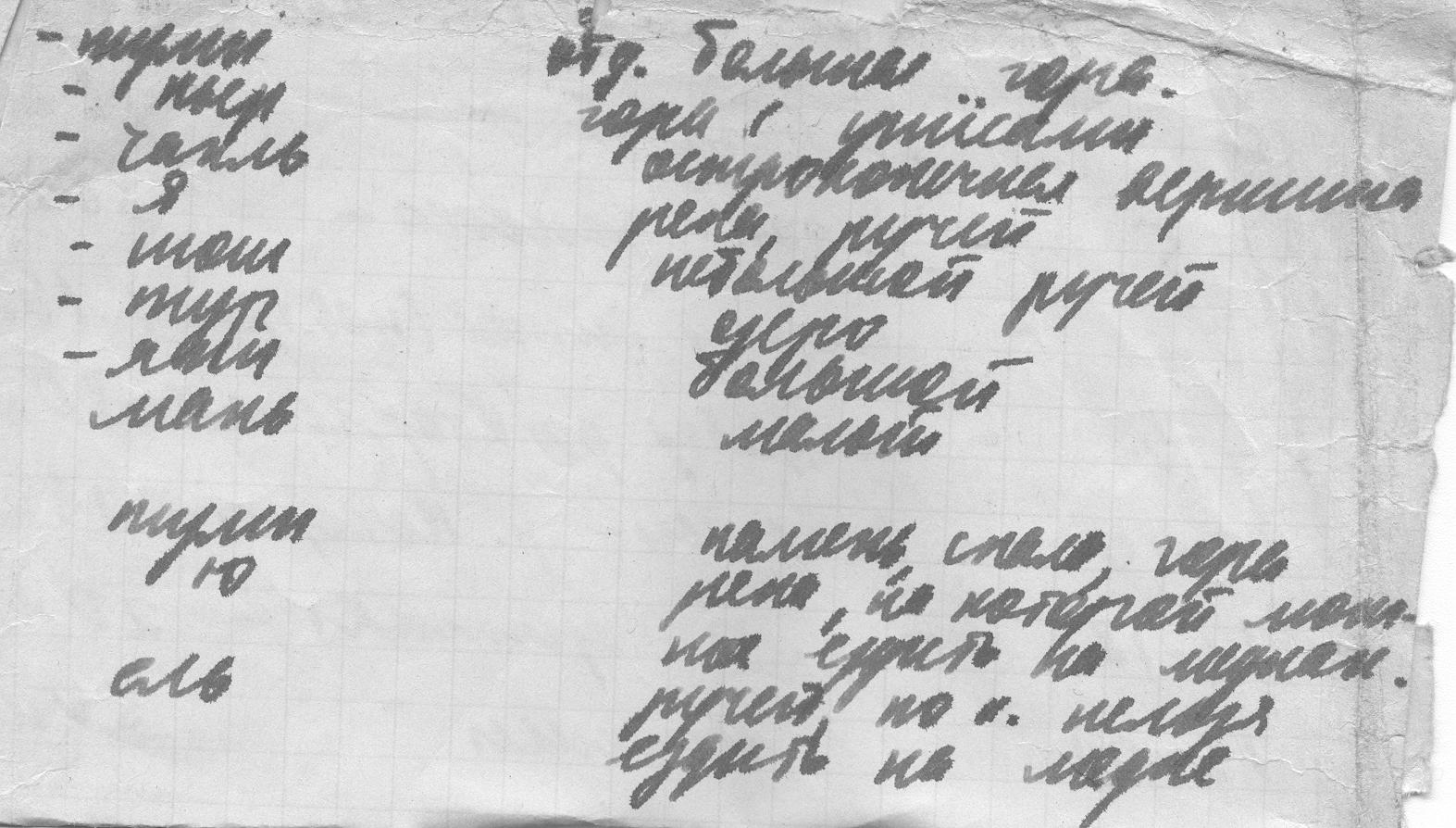

By the way, in the Mansi language "u" means "a river on which you can sail a boat".

A page from a camping dictionary of Mansi words taken from Hoffman’s book

I scanned the mini-dictionary of Mansi words that was with me on that trip. The words relate only to some geographical names; they were written down before the trek and were taken, it seems, from Hoffmann’s book. My handwriting was terrible; I couldn’t read everything myself.

- 11 -

It’s hard for me to imagine, judging by what I still remember, the very possibility of active military activity in those places, somehow it doesn’t seem like it. And the planes didn’t alarm us at all then. You never know what they could do there. What if it was a training flight? Now I'm almost sure that it was just an ordinary aerial photograph. What I described in my diary as circling above us could well have been the same back-and-forth tacks that the pilot was talking about. By the way, as far as I remember, the plane did not fly directly above us, but somewhat on the Asian side, and at a fairly high altitude. Its appearance at the moment of our approach to the ridge can also be explained simply. It was at this time that the weather cleared and the sun appeared, and before that there were clouds and it often rained. And we, being in the taiga, did not look at the sky very often.

M.P.: It turns out that I unwittingly pushed you to change your testimony about airplanes. You remembered new details. It's a pity how much intrigue there was. I liked it so much! But what can you do, the truth is more important. This is why I examine the evidence from all points of view in order to come to a definite conclusion. But I would like to add an addition to your words about the weather. The weather, judging by the diary entries, was sunny and hot already on July 23, and your group reached the slope of Kholat Syakhl on July 25 and climbed it on July 26 to continue the journey to Otorten. And it was on these two days that planes appeared and flew over you for a long time. Then the planes in the sky were no longer mentioned in the diary. Maybe it was an accident that they were flying over Kholat Syakhl when you passed there, or maybe not. You see, I don't give up.

B.G.: As for the plane, I don’t believe in its appearance there for our sake. No, I resolutely reject this intrigue. By the way, I noticed that you now know my diary much better than I do, for which you have honor and praise.

M.P.: Because I like it, very interesting!

Boris Sergeevich, you write that the group went down to spend the night and did not stay overnight on the slope. 'As already said, we spend the night at height 1079. Again we had to go deep down, but this time to Europe, to the sources of one of the tributaries of the Unya.' Why did you go down to the Unya, and not to the tributaries of the Lozva? Why couldn’t it be possible to spend the night on the slope, so as not to waste time climbing in the morning, but to immediately go further along the ridge?

B.G.: We went down to spend the night "in Europe" because it was more convenient and closer. Other times we set up camp "in Asia". Well, it’s just very simple: on the ridge there is no water or wood for a fire, so we had to go down to the edge of the forest.

M.P.: This seemingly obvious rule was violated in the case of the Dyatlov group, whose tent was set up on a windy slope in winter, not in summer! Without the necessary supply of firewood. At that time, when there was a forest below, it was warm, there was firewood. This oddity in choosing a place to pitch a tent is noted by some researchers familiar with hiking rules and practices. Either the Dyatlov group were forced to set up a tent on the slope for some unknown extreme reasons, or it was not the Dyatlov group who set up the tent.

Boris Sergeevich, have you gone on winter hikes? How did you set up your tent in winter? In a treeless area, did you set up a tent on skis with their bindings facing down?

B.G.: I’ve been on ski trips, but I’ve never had to pitch tents on skis, I’ve never even heard of this method. The spruce branches were always there, but we didn’t have the chance to spend the night in treeless places. But for a fire, we dug a hole in the snow right down to the ground, this created additional comfort and prevented the heat from dissipating too uselessly. That's how it seemed to us, anyway.

Maya Leonidovna, I would not attach special significance to this issue, much less look for a sinister meaning in it. Firstly, moving in winter, through deep snow, is much more difficult than in summer, and the guys could simply feel sorry for returning, "no one will take away the path we have traveled". Secondly, as far as I understand, they didn’t go that far from the edge of the forest, where they later ran in a panic, and could well have decided that they could send a couple of the strongest guys for firewood. Thirdly, once it was possible to give up hot food and get by with dry rations, because they found crusts of brisket or something like that in the tent.

M.P.: How about the weather there, on the slope of height 1079, strong winds? For some reason this is not mentioned in the diary.

B.G.: We did not encounter any special winds on the Ural ridge on that trip. But this was in the summer, in July, and journalist Gennadiy Grigoriev described what happens there in the winter.

- 12 -

M.P.: Boris Sergeevich, why do they decide to quit smoking during a hike? So the Dyatlov group also promised to quit smoking, and they found "Aromatic" cigarettes in their belongings. And your smokers suddenly bought cigarettes on the route, although they decided to quit smoking during the hike. How does smoking interfere?

B.G.: In 1956, I had not yet smoked, and it is difficult for me to answer why it is on hikes that people decide to quit smoking. Maybe because it’s not easy to get a smoke far from residential areas, and external circumstances seem to be pushing towards this difficult decision. But since I am now a smoker of over 40 years, I can confirm that it is very, very difficult. You, as a non-smoker, are unlikely to understand this.

M.P.: Boris Sergeevich, what does the group leader do if one of the hike participants suddenly gets sick along the route? Have you ever had such cases while hiking, what did you do in these cases? I want to understand why Igor Dyatlov let Yuri Yudin go alone, although there was a driver there, but the driver drove far ahead for a whole three hours, and Yudin walked alone all the way. What if something happened to him on the way back? There was no accompanying person with him. And the group did not stay at 2nd Northern for a day to wait for news whether Yudin reached the 41st district safely. Moreover, he was allowed, sick, to go with the group all day to the 2nd Northern. It seems to me that this was somehow an ill-considered decision.

B.G.: I think that in each specific case a specific decision can be made. I can’t know what kind of condition unfortunate Yudin was really in, what kind of person the driver was. If Dyatlov and his comrades left Yudin alone, it means that they did not consider the situation threatening. On another trip, in the Caucasus, one of the guys severely cut the skin on his head, there was a lot of blood. We sent him and another guy to the nearest medical center, and we ourselves waited for them on the spot for two days. Fortunately, it turned out to be nothing serious.

M.P.: In the same case, a certain irony of fate appeared: the sick Yuri Yudin returned from the trek alive and unharmed, and lived a long life. And the healthy members of the group died a few days later. A similar case of dividing a group into sick and healthy, when the healthy did not accompany the sick to the nearest settlement and soon died, while the sick and injured survived, occurred in the summer of 1961 in Transbaikalia, also with UPI students. There were seven people in the group, but three, including a girl with a broken leg and the leader, who was also injured on the descent from the Bear Pass (Kodar Range), returned, and the remaining four for some reason continued the route and died.

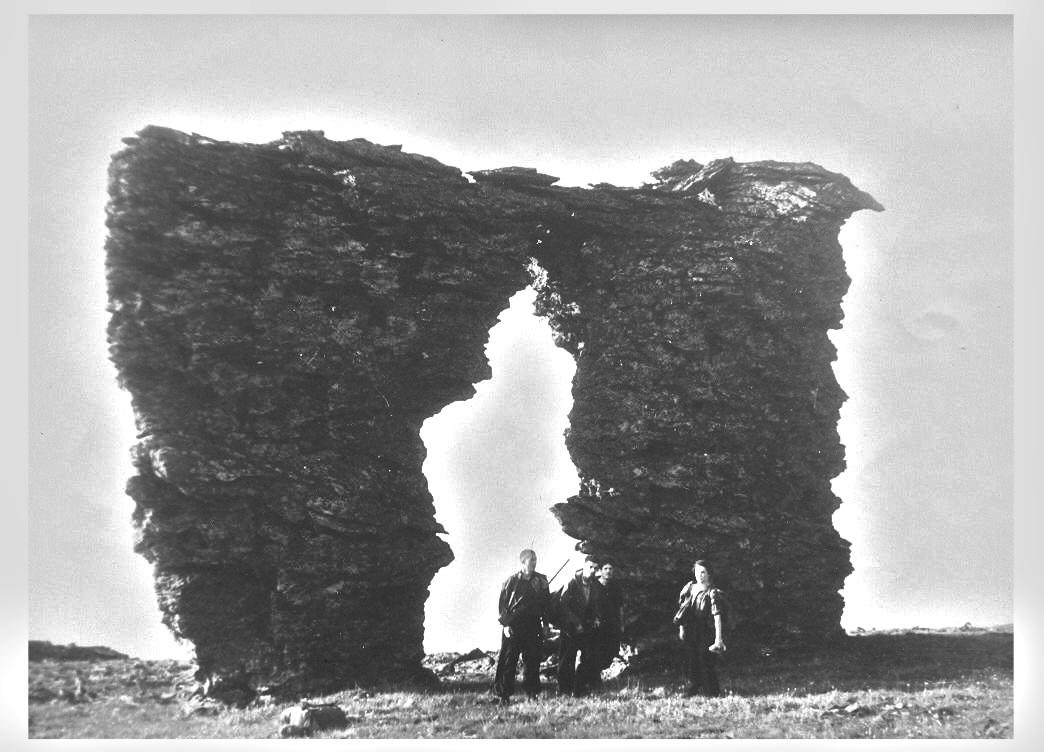

Boris Sergeevich, on that hike, did any places on the route influence you, instilling unconscious fear? I looked at the travel photos. The places are creepy and wild. Or, in my youth, such things were not noticed, were not recorded by the psyche?

B.G.: No, I didn’t experience any inexplicable anxious feelings on that hike. Such sensations arose as a result of the emergence of very specific situations, for example, due to the proximity of the labor camps. This happened during the 1956 trek, and especially during the earlier winter hike in the Middle Urals. And what you are asking about happened once during a winter hike in the Arkhangelsk region, when we came to a rather large, but abandoned, absolutely deserted village, where loggers once lived. Many completely intact empty houses, impossible silence, frost, a bright moon in a cloudless sky. For some reason I felt uneasy. But we spent the night there, and in the morning there was no trace left of the night’s fears.

M.P.: What happened during the winter hike in the Middle Urals?

B.G.: This trip to the Middle Urals was organized by the hiking department of the Faculty of Chemistry so that hikers who had already walked a lot could share their experience with such neophytes as we were. So the group was quite large.

Towards the end of the hike, our crowded group came to one of the camps, of which there were many in these places at that time. At night we were given a place in an empty barracks for unescorted prisoners, and in the morning they promised to send us by car to Kizil, since the presence of strangers was extremely disturbing to the labor camp authorities. In the morning, indeed, a truck arrived, which, by the way, ran not on gasoline, but on wooden blocks, and therefore had a high black column on each side of the cabin, in which a fire roared. Some serious argument broke out between the truck driver and the boss who sent him. Unfortunately, we understood its meaning too late: the prisoner driver insisted that he be allowed to stay overnight in Kizil, and the authorities demanded a return to the evening roll call. He was not permitted. As soon as we were settled in the back, the car took off, and a security guard, whose mouth was full of gold teeth, rushed after us, desperately swearing and waving a pistol. He jumped onto the step, the truck for some reason did not rush along the road to the city, but turned into the forest and soon stopped in a gloomy clearing, surrounded by tall pine trees. A huge fire was burning in the middle, and around it were blackened figures of prisoners who were quite unambiguously looking at our two suddenly quiet girls (one of them was, by the way, the daughter of film director Vasiliev and actress Myasnikova - Anka the Machine Gunner from Chapaev). It is true what they say that people on this side of the prison bars are close in spirit and live in the same world. The guard was clearly from this world and spoke the same language as the prisoners, but he still represented the law and was clearly feared. Under his supervision, pine logs were loaded into the car, and we finally got out onto the road leading into the city. The guard left us here. But we didn’t go far, getting stuck at the first small but rather steep climb. At first, the truck made it with a running start almost to the end of the climb, but then powerlessly rolled back. There were many new attempts to overcome the obstacle, we pushed the car together, put spruce branches under the wheels, but every time, almost at the very top, the engine suddenly stalled, and the truck rolled back, threatening to crush the guys pushing it. Then we finally realized that the problem was not the steepness of the climb or the malfunction of the machine. The driver did not intend to make this trip under unfavorable conditions for him.

- 13 -

Meanwhile, the short northern day was over, and we had no choice but to get on our skis and try to walk the remaining 25 kilometers to the city. At first we moved quite quickly along the well-worn road, but gradually fatigue began to take its toll, our legs began to move apart, we took off our skis and then simply pulled them along with us on a rope. In complete darkness we saw some strange barracks on the edge of the road, where we were allowed to warm up for a while. The warmth immediately melted the exhausted guys, our eyes closed involuntarily, and we would have willingly stayed here until the morning, despite all the suspicious conditions of the house, which resembled a den of robbers, if soon we had not been almost forcibly pushed back into the cold. We trudged on, literally falling asleep as we went. It was almost morning when we finally reached Kizil. Oddly enough, the guard of the school, on whose doors we had been desperately knocking for a long time, let us into the gym, where we finally collapsed on the mats covering the floor. No, perhaps it was not Kizil, but some village on the way to it, because it turned out that one of us needed to immediately go to the local car depot, where the working day was just beginning, in order to arrange a car, which would take us to the Kizil station. Although I didn’t have any such responsibility on this trip, the leader was a guy from my senior year, I still decided to show willpower and went with him. What a melancholy the snow-covered, God-forsaken village, illuminated only by the light of dim electric bulbs from the low windows of wooden houses, evokes! And here you can live your whole life? But everything comes to an end, and this test also ended. In the evening we were already sitting in the carriage of a fast train and were heading to Moscow. That's all those unsettling feelings from the hike that I mentioned.

M.P.: Yes, quite a creepy story.

Boris Sergeevich, reading reports on the hikes of other groups, I notice that they took on obligations to note, for example, the level of snow cover, observe nature, give lectures in the places where they travel, all this was included in the plan of their hike and approved by the route commission. They even took supporting documents on the spot, certificates stating that they had held such and such a lecture in such and such a locality. From the diaries of Igor Dyatlov’s group it is clear that they also performed at school in front of children, but it was not a planned performance, but rather spontaneous, because the group was allowed to rest in the school closest to the station. And they could ask the school management for a certificate that the Dyatlov group gave a lecture on hiking for reporting purposes. This was encouraged at the UPI hiking club.

Have you read the report of a group of Muscovite students from Moscow State University for 1954, a hike in the Northern Urals, led by Evgeniy Shuleshko? Do you know any of them personally? Were you required to prepare such reports? And in general, how was the report on the trek written, the same as a diary, or was it significantly different from a camp diary? Who was this report given to? And did you have to write it down, or could you just copy the travel diary and submit it to the relevant authorities?

B.G.: No, I don’t know the participants in that hike, they were several years older than us, and at 19-20 years old that’s a lot. Looking through their detailed and very practical report, I felt like a complete amateur in the face of professionals. We did not write such reports, and now I doubt whether we wrote them at all.

Unfortunately, we have never been assigned any responsibilities for observing nature. The same applies to lectures. And who could we read them to in deserted places? It’s a different matter on short, easy hikes. I remember we took part in the so-called "star" in the Kalinin region, when several groups converged from different places to one point in some regional center, I don’t remember which one, and organized an amateur concert there.

Reports on hikes were written with the aim of making it easier for followers to complete their routes, and contained descriptions of local features, recommendations, specific tips, and tips. These, of course, were not travel diaries. The reports were supposed to go to the library of the Tourist House, or whatever it was called (at least not “authorities”), but I don’t remember any fears of any sanctions for non-compliance. And we didn’t register our last couple of trips at all; we went without official documents.

M.P.: As Vladimir Askinadzi told me, the first copy of the report was always sent to Moscow and kept in the library of the All-Union Tourists Club, on the Sadovo-Kudrinskaya St. And a special section was highlighted in the report, which outlined relevant recommendations on how to navigate difficult and dangerous sections of the routes. Whether the leader adheres to them or not is his business, but there were recommendations. This library has accumulated so much unique hiking material. There were reports on all category hikes, above two, from all over the Union, on all types of tourism, hundreds a year! They say that when this mansion was taken away from tourists during Yeltsin's reign, everything from there was thrown into the street, and some enthusiasts saved some things and dismantled the library into their apartments.

M.P.: Returning to the question of the protocols of the route commission, as you did at that time with the organization of control of hiking traffic. Indeed, in the Dyatlov group, sports bosses of all ranks began to blame the unfortunate Igor Dyatlov for not submitting the protocol of the route commission to the UPI sports club, so they did not know where to look for them. In addition, the chairman of the UPI sports club Lev Gordo stated that the final goal of the route of Dyatlov’s group was Otorten, as if erasing other peaks from the route. Among the belongings of the Dyatlov group found in the tent, there suddenly turned out to be a copy of the protocol of the route commission. Why did Igor Dyatlov need to carry this piece of paper on a hike? What such a terrible thing could happen if the protocol was not submitted where it should be, i.e. to the UPI sports club? And Dyatlov had never seen anything like this before, so that he forgot to hand over the necessary papers somewhere. He, a sports activist, chairman of various hiking commissions at the UPI sports club, a future secret defense industry employee, himself clearly understood this and thought about his career. How he methodically prepared for the hike, what lists he made of things needed on the hike, and wrote down every little detail. And suddenly he forgot to hand over the protocol and took it with him on a hike. As Vladimir Askinadzi explained to me, "if the group had not died, and they would have been forced to rescue them, Dyatlov would definitely have been disqualified for this to zero! The rest of the trip would have been counted. Why didn’t he leave the necessary information for the controlling organization? Apparently, the reason is the ubiquitous Russian carelessness.

Yes, the fact that at the beginning of the search they did not know in which part of the route to look for him is carelessness. But the reason for the carelessness is not in him, but in the general situation with control over routes. Hiking, as a mass phenomenon at the institute, was quite young; by that time it was only five years old. Timid signs of organization were just beginning to emerge. There were no examples. They copied organizational structures from other sports where there was no reporting on the process of holding competitions. In Moscow, by that time, structures of an all-Union scale had not developed, although hiking itself (of local significance) existed. Both the routes and the leadership team were quite qualified. It was not for nothing that at the beginning of the search they invited Kirill Bardin, a Muscovite, Master of sports, as a consultant. Of course, before Dyatlov, both groups and individual hikers died. But there was no such resonant event in the Union; the Government itself contributed to this. The revision of norms and requirements, especially for routes of the highest category, began in the Union precisely with the death of the Dyatlov group. The situation was further aggravated by the fact that by 1959 there were no emergencies in the club, even on a small scale. Dyatlov did not leave any documents, since no one demanded them from him. Gordo and Slobodin did not know this specificity of hiking."

- 14 -

B.G.: Apparently, I became interested in hiking when the hiking structure was just taking shape, because I entered Moscow State University in the memorable 1953. Many of the features of the planning of treks that emerged a little later remained unknown to me. I don’t know what the protocols of the route commission look like. Maybe in our prehistoric times they did not yet exist, but I personally have not had to deal with this. The route book existed in one copy. They most likely received it (I may have already forgotten) from the city route commission (unlikely from the university) and submitted it there. It was needed not only on the hike itself, but also to obtain at the university the wretched equipment that we still received. I don’t remember any troubles related to the route book.

M.P.: As I understand it, despite the emergency, Sverdlovsk, in comparison with other hiking clubs in the country, even in the capital, was still "ahead of the rest" in organizing and controlling hiking. They required protocols of commissions, route books, and monitored the registration of ranks and the compliance of groups with the categorization of their future routes.

B.G.: We went on the last couple of trips without any registration, without route books, without cover letters, without the goal of obtaining a sports category. Why did we need this? A friendly group just got together, got what they could and prepared equipment, bought tickets and went on a trip. In 1957, on a kayak trip along the rivers of the Arkhangelsk region, including Onega, my friend and I immediately recovered from military training, taking, to the surprise of the military authorities, a military letter (the right to free travel) not to Moscow, but in the opposite direction, to Nyandoma station, where we reunited with the rest of the group. The next year, when most of the guys had already completed their university course (and I, as part of my special group, had to study for another six months), we went on a hike to the Caucasus. It was precisely because of the lack of official documents that we were forced to pass through the Klukhorsky pass, where there was a certain barrier outpost, in the shadow of the night, trying to step quietly so as not to disturb the guards. Everything worked out, however.

M.P.: You wrote in your diary that somehow you were carried quite far to the north, and you ended up on the upper reaches of Malaya Toshemka, crossing one of its sources and reaching the second. 'Apparently, we was in vain to go from the hut on the pass to the booth and further along the stream, thereby deviating to the north, and did not take into account the magnetic declination (17 degrees)."

How did you determine the magnetic declination?

B.G.: I can’t say anything about magnetic declination, I don’t remember. I notice that more and more often I have to answer "I don’t remember" to your questions; apparently, my memory resources are close to exhaustion. And these questions somehow move further and further away from the topic of the tragedy of the Dyatlov group.

M.P.: Boris Sergeevich, every detail matters. It’s not for nothing that I’m asking you about things that seem to have nothing to do with the tragedy of the Dyatlov group. In fact, I am looking for answers to my personal questions on the topic of tragedy. And I have already found many, thanks to you and your hiking diary.

Boris Sergeevich, here’s a question for you: what does it mean, a hikers-type campsite? How does it differ from another type of camp, non-hikers? Was the fire not that complicated or what? What remained there at the campsite, what could hikers or non-hikers know from these signs? Here you wrote about a campsite that you stumbled upon in the vicinity of Otorten: "We are standing on the site of someone’s camp, apparently abandoned not so long ago. It's strange who it could be. There have been no hikers here yet, and the camp is clearly of a hiking type. Maybe an expedition..."

B.G.: Why did we think that the camp was a hikers type? It’s just that the traces left were very similar to those we left. Tent marks are about the same size as ours, perhaps struts on which they lay down with a bucket or pot hung on it, maybe empty tin cans. This was clearly a one-night stop. From respectable people, geologists, for example, I think more lasting traces remain. However, we were unlikely to seriously analyze our impressions then. It looks like that's it.

M.P.: What songs did you sing in those years, in the late 50s? Did you always carry a guitar with you, or was the mandolin easier to take and was it more popular than the guitar? They told me that a mandolin was much more expensive than a guitar, it’s unclear why they would carry it on hikes, such an expensive thing.

B.G.: Of course, no one took a guitar, much less a mandolin, on serious hikes. This was possible on short, recreational hikes, for example, along the Seliger River or along the Seversky Donets; these also happened to me. Probably our main hiking group was not very musical, they didn’t sing very much, and they were usually very tired by the end of the day. What were we singing? I'm afraid to lie, songs from different times could be mixed in my memory. They sang "Along the Tundra, Along the Wide Road", "Globe", "Brigantine", "Harness up the horse" (this was after the military camps), songs by Gorodnitsky, Vizbor (this was apparently later), I don’t remember everything, although some things still pop up in my brain from time to time.

M.P.: Boris Sergeevich, you wrote in your diary that all three watches you took on the hike were already damaged in the middle of the hike. And this story happens every time. Why did your watch break during your hike? If I'm not mistaken, watches at that time were quite expensive, many did not have them at all.

- 15 -

B.G.: Who knows why they broke. It was indeed quite an expensive thing back then. My parents gave me my first watch after graduating from school, but already in my first year I lost it. It was simply removed from me in a dark place on a deserted street near the Danilovsky market in Moscow. I was very proud of the second watch; it had luminous hands and numbers and was considered shockproof. But upon impact, some kind of spiral simply twisted inside, and they continued to count down time at double speed. Any watchmaker could easily return them to their normal state, but in the conditions of a hike it was impossible to do this yourself.

M.P.: As you probably know, two pairs of watches with almost identical time readings were found on one of the bodies in the ravine: a sports watch that showed 8 hours 14 minutes 24 seconds. The Pobeda watch showed the time 8 hours 39 minutes.

In your opinion, why did the man have two watches? What are your thoughts? You have been on hikes, did you know exactly which watch belongs to whom? It was so important to find out the time on a hike, or you could easily do without a watch away from populated areas. They say that there was a custom among hikers when they were on duty to wear two watches so as not to oversleep. Is this true? How did you wind up the watch during the hike?

B.G.: On my hikes, I, of course, knew who had what watch, especially since, at least in the first hikes, there were never more than two, and more often just one. The time, of course, had to be known, at least in order to designate the moments of halts, overnight stops or morning rise. Our guys on duty never had two watches, and I usually woke them up, as the only keeper of the exact time. When they were on duty at night in shifts, I gave the watch to the first person on duty, and then it was passed on to the next one. I have already told you that sometimes we were left without a watch at all. Then we used a compass during the daytime and if there were at least some signs of the sun in the sky. After all, exactly at 12 o’clock in the afternoon, and taking into account the current time zone - at 13 o’clock (then, as now in Russia, there were no summer and winter time, but now the discrepancy with the astronomical time is 2 hours), the sun should be exactly in the south. You place some stem or stick vertically and see how many degrees the shadow deviates. Over the course of an hour, the position of the shadow should shift by 15 degrees. This is, in fact, how the sundial works. The method is not very accurate, but it is what it is. I personally am used to winding my watch in the evening before going to bed. I think this is what most people did and do if they use mechanical non-self-winding watches, which have already become a rarity, but somehow it never occurred to me to check this.

M.P.: Vladimir Askinadzi said that at that time "watches were not so much a luxury, although that was also the case, but, especially among students, an indicator of belonging to a non-poor class. It's like today, a diamond tie clip." Therefore, he assumes that both pairs of watches were taken from others, for example, from those who froze under the Cedar tree, which fact can be interpreted in another way: the guys in the stream did not expect to die when there were already dead people under the Cedar tree. Boris Sergeevich, I wanted to know, what do you think about the cause of the death of the Dyatlov group? What do you believe happened?

B.G.: You, of course, know that last summer near the city of Serov, i.e. all in the same area, a small AN-2 plane disappeared, the wreckage of which was found only this spring. There was a lot of hype about this again, again TV shows, again theories, one more fantastic than the other. I won’t talk about the details that are probably familiar to you, but this tragedy, like the tragedy of the Dyatlov group, occurred in the same local "Bermuda Triangle", and both events are naturally connected with each other. I absolutely do not accept most of the ridiculous explanations for the death of the Dyatlov group (avalanche, Bigfoot, Mansi revenge, elimination of unwanted witnesses, internal strife in the group, etc.), but one that can unite both events seems to me worthy of attention. This is an increased probability of occurrence of magnetic anomalies in places, and in the Urals, where the ground contains a lot of iron, such anomalies exist, so-called plasmoids, simply put, ball lightning. What they are capable of producing is not very well known, but they are capable of many things. This version seems promising to me, at least it is far from mystical and has a natural scientific basis. I used to think that if an explanation was found, which I am not entirely sure of (the optimistic statement that everything secret sooner or later becomes clear, alas, is not always justified), then this will happen only after all the archives are opened. Now I have doubts about this. What do they have to hide after more than 60 years?!

M.P.: Boris Sergeevich, you noted an interesting point when you pointed out the appearance of plasmoids in an anomalous area, and anomalous precisely because there are deposits of various metals, especially iron ores. But it’s not clear to me what size plasmoids can be, and whether they are capable of breaking skulls and ribs. It seems to me that all these anomalous phenomena have nothing to do with the cause of the tragedy; after all, human beings tried. It was simply murder. It is the murders that the authorities could and are still hiding. Moreover, for some reason, all the crimes committed by the state and the military are already known: the Totsky training ground, the executions in Novocherkassk, but this case remains a secret, despite the fact that the criminal case has been released to the public for review. The reason for the death of the group indicated in this case file can only satisfy a narrow-minded person.

In addition, rumors about the involvement of the military and their secret tests were skillfully spread in society in order to distract people from other thoughts about what happened. After all, the way we argue is that if you say that there were military tests of a secret weapon, then everyone will understand that it could have been hidden, and the reason why the authorities are hiding it is clear. Lately, ufologists have been in vogue with their own version, and they consider alien mechanisms to be the culprits in the death of the Dyatlov group.

- 16 -

B.G.: So, are you inclined to the point of view that the Dyatlov group were killed, and they were killed not at the state, but at the local level? This, to be honest, did not occur to me, and there is a lot of reason in this version. Although not everything fits completely in it, questions remain. First of all: who and why? Why did no one ever mention, no one saw outsiders? Why is a local crime still so carefully hidden? Or maybe all the documents, if they existed, were destroyed long ago? And could the local government be so unafraid of the central government (given the extreme hierarchy of the Soviet state system) that it was able to hide all the loose ends among its native aspens? And why then did the investigator go to Moscow? Or maybe several reasons came together?

I also don’t know much about plasmoids, but they can cause very serious destruction.

I would like to thank you for Makushkin’s materials, it was very interesting to me. I wish you had more such interlocutors - intelligent, modest, knowledgeable and responsible for their words.

M.P.: Thank you, Boris Sergeevich. As I expected, many did not understand anything at all in these materials. People are waiting for "fried" facts, ready-made conclusions. But for me personally, a picture has long begun to emerge that the way it was presented to us in the well-known case files was in fact different. Many materials were simply removed from the case. Many important examinations were not appointed, and those examinations that were forced to be appointed by law were incomplete due to the fact that important key questions were not posed to the experts. And the whole effect was adjusted to one cause - an overwhelming elemental force. This was also confirmed by the daughter of investigator Lev Ivanov, telling how her father collected the facts indicated to him, built a conclusion and closed the case, that he did as he was ordered. That in Soviet times nothing was said about this, especially at home. Only in the 90s, when it was already possible to start talking about this case, Lev Ivanov said that he was a communist, and he had a family, and he could not do anything other than classify the case. But investigator Ivanov did not dare to tell the truth about the Dyatlov group’s case, putting forward a harmless and fashionable version at the time that the Dyatlov group was killed by a UFO, although he himself did not believe in alien intelligence and was never interested in science fiction. Perhaps, when he said UFO, he meant a rocket of entirely terrestrial origin? May be. But Lev Ivanov’s daughter is convinced that her father specifically put forward the most fashionable version at that time, the UFO version, in order to somehow attract public attention to the forgotten case of the Dyatlov group.