"How we didn’t get to the moon"

Sergei Leskov "How we didn’t get to the moon", newspaper "Izvestiya" from August 19, 1989

Several years ago, K. Gatland's encyclopedia "Space Technology" was presented at the Moscow Book Fair. You could easily go to the stand and look through this colorful edition. The book probably suffered from the usual flaw in popular science literature: it was complicated for amateurs, too banal for specialists. Nevertheless, the encyclopedia caused a sensation in scientific circles. Many scientists, including the most qualified ones, specially came to the fair just to look through the encyclopedia.

Of course, it is naive to assume that Soviet specialists in space technology have to replenish their knowledge in such an unreliable way. Interest in the exhibition copy was caused by completely different reasons. In it, next to the huge American carrier Saturn-5, which brought the Apollo spacecraft to the lunar track, a similar Soviet H1 rocket was reproduced, the development of which was considered one of the strictest secrets of our space industry and which, of course, was never mentioned in our literature.

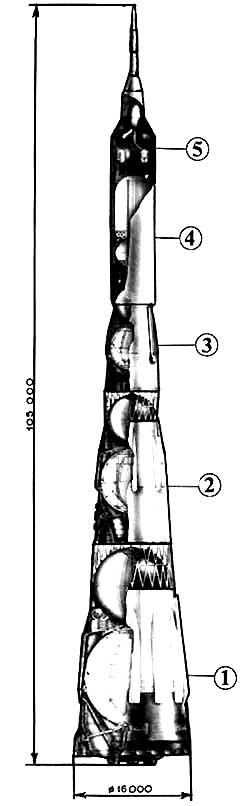

| N1-L3M rocket and space system:

|

Source Astronaut.ru

However, in the age of intelligence satellites, many secrets, no matter how much you keep them, come up. So it was no easier to hide H1 from prying eyes than, say, hiding a giraffe in a chicken coop. Several times in the 60-70s, the giant cigar H1 was taken to the launch sites of Baikonur, where it was photographed by all-seeing spacecraft.

About the origin of the exact, compartment-by-compartment, drawing of the H1 rocket, I, when visiting Baikonur, have often heard a curious legend. I do not presume to judge its authenticity, but the myths serve as a very characteristic illustration of strictly kept secrets. So, the old-timers of Baikonur whispered the story that a deeply embedded spy was working in one of the buildings next to the assembly and test building (MIC), from where the rocket is taken to launch on a special platform. His only task was to sketch the H1 rocket, and in order not to arouse suspicion, he worked hard for many years for the glory of Soviet cosmonautics, receiving red pennants and honorary diplomas for victories in the socialist competition. No one could have suspected this cunning man. The most ordinary engineer, without any oddities. Then, when the exact characteristics of H1 were discovered in the West, our counterintelligence officers caught on and somehow figured out from which window they were looking at H1 and who exactly was peeping. But it was too late — there were no traces of the spy left, he had left long ago. I repeat: I don't know if this is true or not, but myths are also quite characteristic of history.

By the way, "Space Technology" with the "necessary" abbreviations was reissued in the USSR, excluding from the text any mention of H1, not to mention the semi-criminal drawing. There is an empty space left on the sheet-guess what was there. The story was repeated with secrets that the whole world knows about, but which cannot be told at home. But that's not even the point right now. It seemed that H1 was destined to be forever persecuted. Even in 1989, when Glasnost no longer knew any barriers and forbidden zones, it cost me great effort to publish an essay in one of the central newspapers, where the story of H1 was first told. Surprisingly, not every specialist involved in the creation of a rocket that was written off to the archive a decade and a half ago agreed to share his memories. No, I was hardly mistaken for a foreign spy who tried on the mask of an ignorant journalist. But the notorious "nondisclosure agreement" weighed people down, even though it had long been clear that from a technical point of view, only a museum exhibit was behind the protected fence. Unfortunately, the arguments that distorting history and omitting information about real events would inevitably lead to new and much more cruel mistakes did not work for everyone. But many, not considering it possible for themselves to be cautious, helped to understand one of the most significant projects of Soviet cosmonautics. Despite all the differences in their assessments, they were united in one thing: the seal of secrecy does not benefit this industry. I would like to express my gratitude to those scientists who helped me collect this material: Academician V. Mishin, Corresponding Member of the USSR Academy of Sciences B. Chertok, Professor R. Anazov, Associate Professor M. Florianskiy.

I think not everyone knows that until recently, any materials on cosmonautics were subject to the strictest "space" censorship before publication. Needless to say, the most modest attempt at secrecy, any attempt to report something new, get to the problem or publish a sensation-all this was carefully suppressed by vigilant censors. In short, it is not surprising that the popularity of cosmonautics has sharply declined over the years — the promotion of its achievements was extremely clumsy, all the materials were like pawns from one set. Critical analysis and failure were out of the question. But how did you manage to "break through" the visa for the first publication on H1, which occurred in those years when departmental censorship was still alive, but its grip, apparently, weakened a little? Oh, that's a whole story!

- 2 -

I remember how carefully censors from various departments nodded at each other with mock despair, not wanting to take responsibility for resolving the issue. I remember how one distinguished general, radiating the most benevolence, shared his memories with me for an hour, and I patiently, as if in ambush, waited for the right moment to ask the only question that interested me — about the article visa. Finally, he cautiously inserted a word. The other man was taken aback — and, as if from the plague, ran away from me up the carpeted stairs. To be honest, I was in utter despair, I didn't see a way out of this situation. The" green light " was given by the Minister of General Mechanical Engineering of the USSR B. Shishkin. So, the powerful H1 launch vehicle was removed from special reserves — and now each new publication is no longer considered a crime and in some ways complements the dramatic and instructive story...

This preamble describes the atmosphere around the H1 rocket. But what is the reason for such a wary attitude to a powerful car? How to explain the undisguised desire to lower the veil of mystery over its history, when for more or less knowledgeable specialists, one glance at the dimensions of the rocket is enough to guess its purpose? Maybe H1 is to blame for something and they decided to punish it with oblivion, deleting it from the history of cosmonautics? This guess is partly true. Cosmonautics, according to official propaganda, developed in our country under the thunder of timpani, under victory marches. Remember, we even learned about the launch of astronauts when they were already comfortably settled in orbit. The failures, in order not to spoil the immaculate purity of the glorious chronicle, preferred not to mention at all.

Today, the "parade" cosmonautics, which has been smoking incense for so long, causes general distrust and generates many reproaches in their address. And the reproaches, by the way, are not only due to "closeness", they are largely fair-there were plenty of mistakes. But you can't help but wonder if it was worth classifying the dramatic, most instructive pages of the development of our cosmonautics as state secrets. Perhaps, by the way, there would be less drama and unnecessary drama if they solved complex, state tasks not in private, with a narrow circle of trusted persons, but after consulting with knowledgeable specialists who were "rejected" because they did not have the so-called "admission". However, for some, the cult of secrecy was convenient — as a guarantee against criticism.

H1 is called the" last love " of Korolev. From many biographies of the Chief Designer of Space Systems, we know that he dreamed not only of humanity going into space, but also of flying to other planets. We also know that unlike many visionaries, Korolev was able to "bring" his projects to life. The first, that is, a space launch, he achieved. And the second one? Did Sergey Pavlovich really ignore the nearest celestial body to Earth, modestly limiting himself to launching automatic vehicles to it?

In addition, the creator of the world's first spaceships was certainly ambitious. His ambition wasn't to win titles and awards. Circumstances did not contribute to this — being strictly classified all his life, Korolev was even forced to remove the stars of the Hero of Socialist Labor at receptions in the Kremlin, and signed a pseudonym in newspapers. Korolev's ambition is a passionate desire to make a unique car without fail first, to implement an unprecedented project before anyone else. Once Sergey Pavlovich was presented with a schedule with optimal launch dates for the Moon, Venus, Mars, and other planets. Korolev said: "It would be nice to go all over this front and be first everywhere." But the Americans made no secret that they were preparing a landing on the moon. Means...

It doesn't mean anything. Because space achievements are not made in laboratories: success requires money — and a lot of it. This is not the place to return to the now favorite topic about conversion, about the return of money invested in astronautics. All this is true, but at first, allocations for any scientific program are still needed. And you can get them first of all from the military. Ironically, all significant scientific and technical projects of the twentieth century-from the harmless Popov radio to the use of nuclear fission energy-received support and the right to practical implementation only if they were "betrothed" to the military-industrial complex. This fate was not spared by the creator of rocket technology Korolev, whose interests were incredibly far from the military sphere. Nevertheless, he worked hand in hand with the military all his life, and one of the first major assignments Korolev received in the field of rocket science was related to military equipment.

In 1945, Korolev and a group of specialists were sent to Germany to study German developments in the V-2. Sergei Pavlovich lived in Bleicherod in the abandoned villa of SS Sturmbannfuhrer Werner von Braun, a talented German engineer, creator of the first long-range combat missiles and at the same time organizer of the extermination of concentration camp prisoners who served his secret training ground. After the war, von Braun moved overseas and headed many American space projects. They had never met Korolev, but they always seemed to have an invisible rivalry. I would hardly be wrong to say that prior to the Saturn and Apollo missions, Korolev's vehicles were consistently superior in technical performance to von Braun's.

- 3 -

So where was the Korolev to get the funds? Calculations showed that a human flight to the moon would require a launch vehicle capable of launching a payload of 100 tons into a reference low-Earth orbit. But for the foreseeable future, to maintain parity in armaments, the power already achieved was quite enough. Various modifications of the legendary royal "seven" R-7 are still an important vehicle in cosmonautics, delivering from 5 to 7 tons of payload to orbit. But it was already clear to Korolev that the future of cosmonautics lay with much more powerful carriers. Apparently, it wasn't easy to prove it. I judge this by the fact that the very first draft design for a heavy launch vehicle involved putting 40-50 tons into orbit. This is significantly less than what is required for landing on the moon. Korolev had to approach the coveted 100 tons step by step, carefully increasing the rocket's power. V. P. Mishin, then Sergei Pavlovich's deputy, told me that in the early ' 60s Korolev submitted a note to the government detailing a possible scenario for a manned flight to the moon. The subsequent course of events, careful calculations and analyses confirmed that this scenario was the most rational.

On May 25, 1961, US President John F. Kennedy sent a historic message to Congress, where he set the" American nation " a high goal of landing on the moon. The United States, which had lost its primacy to the Soviet Union at the beginning of the space age, wanted a convincing revenge, and in the imagination of Americans it was connected with the conquest of the Earth's satellite. Hundreds of firms, private and public corporations worked together on the Apollo project, tens of billions of dollars were allocated, and the entire course of work was coordinated by a single think tank — NASA.

The USSR did not want to lose its space priorities. But there was no real analysis of the situation, no ability to draw up a single work plan for dozens of enterprises and institutes, to concentrate the necessary forces on the most difficult task, to give an accurate economic justification — this was not the case. On the contrary, each space design bureau worked on its own project. For a long time with the lunar expedition, they swayed, did not make a final decision, which is why Korolev had to finalize the project of his rocket more than once. It is well known how much Sergey Pavlovich was harassed in recent years by having to communicate with the more powerful staff members of the Brezhnev administration. You can imagine with what bitterness Korolev and other talented organizers of the domestic industry watched as our competitors gathered pace, and our best initiatives got bogged down in a bureaucratic quagmire. You can imagine another thing: what courage these people needed to keep up with their goals in an almost hopeless situation. Korolev, being a brilliant practitioner, could not help but understand that the overall victory in the moon race in the current situation of forces is unrealistic. Admitting defeat was not in his nature. Korolev fights to the last. At some stage, he puts forward the idea of flying around the Moon, accurately calculating that at this important intermediate finish, he can be the first, beating not only foreign competitors, but also breaking the resistance of his domestic opponents.

So, the chronicle of events. In 1960, a decree was issued on the creation of the H1 launch vehicle in 1963, designed for a payload of 40-50 tons. In 1961, the decision was revised, the creation of the car was postponed to 1965. 1962 - the plan was revised again. In July 1962, an expert commission chaired by Academician M. V. Keldysh, President of the USSR Academy of Sciences, approved the preliminary design and gave an opinion on the possibility of creating a 75-ton launch vehicle. But it wasn't until 1964 that the moon landing mission was officially launched for the first time. A new search for ways to improve the rocket has begun. In November 1966, an expert commission chaired by M. V. Keldysh gave a positive opinion on the draft design for a lunar expedition using a 95-ton launch vehicle, which made it possible to land one cosmonaut on the Moon, leaving the second crew member in lunar orbit. (The power of the American launch vehicle "Saturn-5" according to the project reached 130 tons, thanks to which two astronauts landed on the Moon.) February 1967 of the year, the decree on the schedule of work is dated, and the deadline for the start of flight tests of H1 is indicated-the third quarter of 1967. It was already known that the Americans will start in 1969. But our specialists, quite in the spirit of the times, were charged with the duty to ensure the priority of the USSR in the study of the Moon.

The seriousness of the intentions is indicated by the fact that a special group was formed at the Cosmonaut Training Center, which was engaged in the Luna program. The size of our cosmonaut squad is traditionally shrouded in mystery, apparently for the reason that this can serve as a good illustration of the significance of space programs. In this case, it is important to emphasize that the composition of the groups that were trained under the unrealized Luna program and the well-known Soyuz program was approximately the same. The lunar group included cosmonauts A. Leonov, V. Bykovsky, P. Popovich, who already had flight experience, as well as O. Makarov, N. Rukavishnikov, V. Sevastyanov, P. Klimuk, who were known only to specialists at that time, and military pilots A. Kuklin and V. Voloshin, who did not wait for their finest hour.

The implementation of the program, as already mentioned, involved two consecutive stages — a flyby of the Earth's satellite ("Luna-1") and landing on its surface ("Luna-3"). At the same time, the new H1 launch vehicle was needed only during the second stage. When flying over the Moon by a ship with a crew of two cosmonauts, the power of the Proton rocket, which puts 21 tons of payload into orbit, was enough. Since the Proton, created in the V. N. Chelomey Design Bureau, was a serial machine, already quite stable, S. P. Korolev thought it reasonable to use it, retrofitted with a special upper stage, to achieve his intermediate goal — a flyby of the Moon. The lack of weight, of course, imposed restrictions on the composition of the crew, the amount of equipment, and due to fuel economy, it imposed increased requirements on the accuracy of the trajectory along the entire expedition path. Many years later, when the Americans got acquainted with the proposed flyby trajectory, they were delighted with its economy and wondered why we didn't take out a patent for a ballistic study of the expedition. Ballistics solutions that managed to find a flight path in conditions of an unthinkable fuel shortage were universal for many space tasks.

- 4 -

Star City was bustling with activity. Excellent simulators were created, and astronauts mastered the technique of controlling the lunar module and the return vehicle. The planetarium studied the surface of the Moon, its relief. For the first time, we had to move away from the usual near — Earth routes-and therefore a lot of time was devoted to studying the starry sky. It was necessary to know not only the northern hemisphere, but also the southern one, for this reason we went several times to the south, to the famous Abastuman Observatory. For the first time, the crews studied the course of space navigation, learned how to use the astroorientator. As the head of the cosmonaut group A. Leonov recalls, the volume of training under the Luna program significantly exceeded the usual limits.

The spacecraft itself, designed to fly to the Moon, looked little different from the Soyuz, but it had equipment on board that was much ahead of its time and found application in domestic cosmonautics only after two decades. Among the most significant elements are the gyroscopes necessary for maintaining spatial orientation and only recently installed on the Mir orbital complex, as well as the onboard computing complex that is currently equipped with the Soyuz TM spacecraft. Once again, the intersection of the Soviet and American space programs. The chief designer of the lunar spacecraft was V. D. Bushuev, later technical director of the Soyuz-Apollo project. Apparently, it is wrong to consider it a mere coincidence that one of the leading designers of the lunar spacecraft, a machine that was far ahead of its time, was the current general designer of Soviet manned systems, Yu.P. Semenov. The most talented people worked for Luna-this is evident from the selection of both cosmonauts and designers.

All maneuvers along the lunar expedition route had to be calculated by the onboard computer system. But, as always in cosmonautics, what is assigned to the machine must be perfectly mastered by the crew — everything happens to equipment in extreme conditions. When preparing for the lunar expedition, working on earth simulators was basically different from anything that astronauts had mastered before. Because at least that all operations with the lunar ship should have been carried out not at the first, "near-Earth", but at the second space speed, that is, almost one and a half times faster, And not only in the speed of the matter — since the flight path is not circular, not cyclical, then the opportunity to correct the erroneous maneuver could no longer be presented.

The most dramatic moment of the lunar expedition A. Leonov calls maneuvers when returning the lander to Earth. Fuel (due to the initial weight restrictions) is already running out. Ballistics maneuvers were unique, never practiced in space flight again. The ship, rushing at a speed of 11 kilometers per second, was slowed down by a double "dive" into the atmosphere. The first time he entered it over Antarctica, emerged from the air shell back into space and, once over Africa, again, at a lower speed, headed for Earth. At the same time, after the first dive, the crew (for the on-board computer of that generation, the task was too complicated) in a matter of seconds, calling on intuition to help, determined the angle of attack for the second dive. If the angle of attack had been less than the required angle, the ship could have slid through the atmosphere like a skimmer and gone into space for at least two more days. With an increase in the angle of attack, already significant overloads increased (five times during landing) , and landing in a given area would then be disrupted. However, even this most complex operation was successfully mastered by astronauts, in total, about 70 tests were conducted in the spacecraft simulator in various modes. The cosmonauts graduated from the helicopter pilot school, mastered landing with the engines turned off on the MI-9 — this was the only way to simulate the landing of the device on the lunar surface.

Based on the results of the exams, Soviet lunar crews were formed. The main crew consists of Alexey Leonov and Oleg Makarov, the backup crew consists of Valery Bykovsky and Nikolai Rukavishnikov, and the third crew consists of Pavel Popovich and Vitaly Sevastyanov. None of them had a chance to launch in the direction of the Moon, but the work on preparing for the flight was huge. But who knew about it? The lunar expedition remained a closely guarded secret, and there was a strong public perception of the cosmonaut squad as a kind of sinecure, where candidates for a flight spend years almost in a lethargic state.

In 1968, the Soviet automatic vehicles Zond-5 and Zond-6 circumnavigated the Moon and successfully returned to Earth. These overflights were hailed as a major success, and they were, but there was still a considerable element of guile in the jubilation. After all, the Probe expedition, repeating in many technical and managerial details the manned project, was not the final, but only a preparatory step for new flights. After the success of the test launches, well-founded proposals were put forward about the appropriateness of a human launch to the moon. But S. P. Korolev was no longer there, and someone had to take responsibility. While they were weighing it up, while they were delaying the decision in the usual bureaucratic style and sending new "Probes" around the Moon, the expedition was carried out by Apollo 8 under the command of F. P. Blavatsky.Bormann. But Soviet cosmonauts — say, A. Leonov and O. Makarov-could have been the first to look at the far side of the Moon. The point is not even in priorities per se, but in their stimulating effect on our entire lives. And it is no coincidence that during the period of stagnation, bold technical projects, including in space exploration, so rarely came to a successful conclusion.

But is it fair to draw parallels between time and the people who are destined to live in this time? I had to talk about the lunar expedition with many engineers — for all of them it was one of the happiest periods of their lives. If one of the leading developers left work on time, he felt almost like a moral criminal, a person who evaded his official duties. M. S. Floriansky, then a very young engineer, told how readily his colleagues grasped each task of the Main One: "Think about it in a week-how is this option?" Literally all the elements for a powerful space complex had to be actually created anew — the launch complex, the refueling system, the control systems, tracking the rocket, production facilities, test stands, not to mention the spacecraft itself.

- 5 -

But the issue of the delayed development of the powerful H1 launch vehicle remained fundamental for the flight and landing on the moon. The problem was much more complicated than flying around the Moon, and there was no need to hurry in such a matter, but the schedule of work was feverish with an unnecessary race with the Americans...

Academician V. P. Mishin, who after the death of S. P. Korolev in January 1966 was appointed chief designer of space systems, has preserved a transcript of one of the meetings held by D. F. Ustinov:

— In two months, a holiday, and the United States will fly again, and we? What did we do? And imagine the picture of October 67. And I ask you to understand this! Everything personal and addictions must be clamped down!

Grandeur, the desire to report on success, to speed up the case, even to the detriment of the case itself, are unacceptable in any field, but especially in cosmonautics, which is associated with high risk and large material investments.

In such an atmosphere, the preparation of the lunar expedition and the construction of the H1 rocket continued. But subjective difficulties have also gained no less weight. As America raced to success at full speed, Korolev found himself without an engine for the H1. The engine is the heart of the rocket. If it is well-established, then many other missile systems "breathe" freely. If it's not working properly, hundreds of blocks and nodes complain about their "health". Create a new engine that would be stronger than the previous one by a dozen and a half times, could at that time in the only design bureau in the whole country, which was headed by Academician V. P. Glushko. This name is famous in the history of Russian science and technology. Back in the early 1930s, Valentin Petrovich was one of the leaders of the Gas — Dynamic Laboratory in Leningrad, developed many widely used rocket engines, and in 1974-1989 headed the Royal Design Bureau, was the chief designer of space systems. Academician V. P. Glushko, like S. P. Korolev, did a great deal for Soviet cosmonautics, but if we want to draw a true picture of its development, rather than a triumphant one, then we cannot avoid those clashes and disputes that cannot be avoided between major characters who are looking for unknown paths in science. Every scientist who is able to have a say in science and technology inevitably faces misunderstanding and opposition from some part of his colleagues, among whom there may be not only retrogrades, but also outstanding specialists. In the end, Hertz did not believe in the practical use of electric current, Rutherford-in the reality of "taming" the internal energy of the atom.

In this case, everything was complicated by the personal rivalry of the two Main Designers. Both Korolev and Glushko could claim to be pioneers of practical rocket science: one in the early 1930s organized a Jet Propulsion Research Group in Moscow, the other at the same time in Leningrad-a gas — dynamic laboratory. Each of them was not only a romantic, in love with his business, but also quite firmly oriented in the earthly realities, was a major organizer of the industry. The main ones did not neglect advertising their projects, did not disdain — for the sake of the goal! - maintaining your personal image. People who knew Korolev and Glushko closely recall that there was a funny competition between them, even in terms of official cars. One has a Seagull ,but the other has a Chevrolet Caprice! Major scientists, they, I repeat, did not need guides when organizational issues were being resolved. Cosmonautics, which was in the center of public attention, was the focus of political games in the country's top leadership. The main ones (one more outstanding designer, V. N. Chelomey, should be added to Korolev and Glushko) they tried to enlist support at the very top, and the outcome of technical disputes in this "triangle" was often determined not by scientific expediency, but by the sympathies of political leaders. Favor not only from Khrushchev, Brezhnev, or Ustinov, but even from some now-forgotten instructor of the Central Committee, could determine the prospects for the development of a complex industry for years to come. It would be instructive to see how the funding of space programs changed dramatically depending on the reshuffle of the party and state elites. It is known, for example, how things went down for the talented Chelomey after the overthrow of Khrushchev. Against their will, every major organizer of science in our country also had to work as a courtier. The lack of talent in this area among some brilliant researchers could put an end to promising projects.

So, there was intense competition, and the potential of Russian cosmonautics was largely reduced due to the fact that no one wanted to recognize the achievements of the other and rely on them. A single independent and coordinating body like the American NASA did not exist in Soviet cosmonautics (and now it does not exist). Hence, the lack of objective expertise and the inevitability of mistakes. But let's be fair and not go overboard in our criticism. For the scale of a scientist is not determined by his lack of mistakes. On the contrary, the mistakes made characterize the scale of the scientist.

So, Korolev and Glushko at that time held opposite views on the prospects of rocket engines. It was clear to both of them that the kerosene and liquefied oxygen used at that time would not be able to meet the growing needs of the space industry. Higher power was provided by engines running on liquefied hydrogen and oxygen, but since their efficiency was sharply reduced in the atmosphere, Korolev did not intend to deviate from traditional fuel at the first stage, achieving its maximum thrust. It would be good to put hydrogen engines on the second and third stages, and Korolev began searching for developers of a new direction. In this he was supported by Keldysh (Korolev and Keldysh were generally allies, like-minded people on most fundamental issues, and this largely predetermined the decisive breakthrough of Soviet cosmonautics at that time). Talented designers A. M. Lyulka and A. M. Isaev were given instructions on the hydrogen ,but they could not make it to the right time. The Americans on their Apollo went exactly the same way and managed to brilliantly justify their plan in practice.

- 6 -

Glushko's concept at that time was exactly the opposite. It seemed to him that the best fuel components in rocket engineering would be fluorine, nitric acid, dimethylhydrazine (otherwise heptyl). Yes, their technical characteristics during combustion are quite high, but they are extremely toxic and dangerous substances for humans. Heptyl, for example, is much more toxic than mustard gas, known as one of the most powerful toxic substances. In the 60s, Glushko repeatedly stressed that hydrogen is unpromising in rocket technology. (Later, at Energia ,he had to refute the previous misconceptions himself.) Distrust of hydrogen can be attributed to inertia, conservatism. But Glushko had a certain logic: the low density of hydrogen requires large tanks, worsens the weight characteristics of the rocket. Glushko could not foresee a revolution in cryogenic technology. Glushko engines with toxic components were by no means bad, they went into production, they were installed on a number of combat missiles that ensured the security of the country. But Korolev strongly objected to their use in manned space exploration. The death of Marshal Nedelin during the testing of one of the Yangel rockets, although not directly related to the problem of toxicity, emphasized the importance of error-free handling of fuel and the accuracy of its selection. Apparently, with a different fuel, there would have been fewer victims in the largest tragedy in the history of cosmonautics.

Here I must make a reservation: some readers may find the following descriptions of technical disputes boring and dry, but people who are at least somewhat close to technology and science will probably find our story light and unreliable without such details. So in advance, I ask some readers to be patient and try to explain the essence of the technical differences around H1 as briefly as possible, without omitting what is still necessary.

Irreconcilable differences between the luminaries of Russian cosmonautics concerned not only fuel. Refusing the proposed cooperation, but not wanting to stay away from the prestigious project, Glushko suggested starting the development of an intermediate-type carrier. In the 60s, in one of his letters, he addressed the Korolev: "It seems extremely timely to immediately start developing a carrier based on a modified R-7 rocket. A different decision threatens the priority and prestige of the Soviet Union in the conquest of space." (R-7 is an intercontinental ballistic missile designed by Korolev, equipped with Glushko engines, on the basis of which the famous Vostok and Soyuz spacecraft carriers were created — S. L.) Korolev replied to this: "It is impractical to make any intermediate version of a heavy carrier instead of the H1, as this will distract forces from the main task. The most important task of expanding space research is to create the H1 object as soon as possible, and we should not be distracted from this task." It was not possible to find a common language, and Glushko offered cooperation to Chelomey, who was also going through hard times at that moment. As a result, the Proton rocket was created, which is still used to launch orbital stations and interplanetary vehicles. Thus, it would be a clear injustice to reproach someone for avoiding work, in search of an easy life. But everyone tried to go their own way. The dispersion of forces has significantly weakened the intellectual and industrial potential of H1.

In short, Glushko boycotted the H1 system, putting in a difficult position not only Korolev — the entire project of the lunar expedition. Whatever he was guided by, the entire long-term plan for the development of domestic cosmonautics was under attack. This is the subject of a different story, but the H1 rocket was also used for other remaining unfulfilled space projects. The situation is deadlocked. As is well known, both Korolev and Glushko were subjected to reprisals at one time (although less severely). So, during the period of acute and hopeless disagreements between the Main Designers, as eyewitnesses of the events testify, many people remembered Stalin with regret, under which it was impossible to flinch. However, both anarchy and despotism are not the best options.

Korolev had to urgently look for other engine specialists...

In the early 60s, as you know, there was a reduction in aviation, many factories were deprived of orders. Thus, helping each other out, the S. P. Korolev Design Bureau and the N. D. Kuznetsov Design Bureau in Kuibyshev* began to cooperate, where engines were developed for many types of domestic aircraft, including the famous TU. In a short time, thanks largely to the chairman of the Kuibyshev Council of People's Commissars V. Y. Litvinov and the secretary of the regional party Committee V. I. Vorotnikov, the necessary production facilities were allocated. 28 enterprises worked for the space order. Many of them underwent radical technical re-equipment, a number of factories were built specifically to provide all the necessary H1. Since then, Kuibyshev has become one of our space capitals.

* in 1991, the old name of Samara was returned to the city.

But since the Kuznetsov Design Bureau, in principle, could not "pull" on a large rocket engine, and time was already running out, it was decided to design the H1 propulsion system from a large number, a "package" of medium engines. This, however, posed a new challenge: to achieve complete synchronicity in the work of three dozen engines. For this purpose, a special "Kord" system was developed, which was supposed to turn off the stalled engines in a timely manner. The design power of the propulsion system assumed that out of 30 engines, any three pairs could be switched off painlessly for the start. But if the plan on paper could be implemented... For comparison, it is interesting to note that the Americans on Saturn 5 equipped the first stage with five powerful oxygen and kerosene engines, and on the next stages for the first time used liquid hydrogen, so disliked at that time by V. P. Glushko.

So, what was the new launch vehicle like? In essence, it implemented the idea once expressed by S. P. Korolev about the layout of "rocket trains" in orbit for flight to distant planets. Only this time the train was made right in the factory floor. The starting weight of H1 is 3000 tons. The first stage consists of 24 liquid jet engines around the perimeter and 6 more in the center (i.e. 30 in total), each with a thrust of 150 tons. The thrust of each of the five Saturn-5 first-stage engines was 700 tons, and Glushko was able to create an engine of at least 500 tons at that time. The already mentioned "Kord" controlled the H1 propulsion system, three pairs of which were reserved, so that with the" silence " of six engines, the rocket, according to the plan, could successfully launch. The second stage of H1 — 8 hollow liquid propellant engines (liquid jet engines) of 175 tons, the third stage-4 liquid propellant engines of 45 tons. The Americans ' second and third stages, let me remind you, were made up of more efficient hydrogen-oxygen engines. The first three stages put 95 tons of payload into low-Earth orbit. Then there were blocks D, D, lunar orbiter, lunar lander-the total weight of these stages reached 95 tons.

- 7 -

The H1 launch vehicle was created a quarter of a century ago, but even today, as many designers who designed it admit, they are not ashamed of their creation. Control systems, measuring equipment, and many design solutions... A number of developers especially highlight the possibility found for the first time in rocket technology to produce light but strong spherical fuel compartments and also for the first time to abandon many of the power elements of the structure. There is, however, evidence that Korolev expressed doubts about these very spherical fuel tanks, which, by tying the hands of designers, excluded the possibility of increasing their capacity, and together with it, the payload capacity of the rocket. Namely, the payload capacity of the rocket, which depends on the power of the first stage propulsion system, despite many ingenious engineering finds, remained the most "raw" part of the H1. It was difficult, almost impossible, for the Kuznetsov Design Bureau, which did not have sufficient experience, to immediately create a synchronously working engine complex without errors, which the world rocket science did not know. Nevertheless, losing to the Saturn-5 in the engine part, H1 made up for the loss at the expense of other systems. As a result, the weight characteristics, the most important indicator of the "survivability" of the design, still remain among the highest in rocket science.

Looking back, you realize today that not all conceptual issues were then subjected to a thorough analysis. This is at least the most important point: where to assemble the rocket — at the spaceport or at the factory? The dimensions of H1 must be such that it cannot be reached by land to Baikonur. When creating the previous rockets, Korolev found an original and brilliantly justified solution: large blocks made at the factory were delivered to Baikonur and here they were docked and checked. This scheme has repeatedly proved itself in the future. But it was not accepted for H1 — you will have to carry a lot of large blocks. Directly at the cosmodrome, where it is difficult with personnel, with everyday life, it was necessary to build the main parts of the rocket at a specially created production facility, where engineers and workers who had left their families were seconded from all over the country... And again, for comparison: the Saturn 5 was built in the interior of the country, and it was transported to Cape Canaveral on barges along a specially dug canal, and then along the Mississippi and by sea. And these costs were justified by the end result.

Now it is already clear that in the engineering part of H1, in addition to useful finds, there were also innovations that cannot be bragged about. In order to save time and money (again this argument! How the rush, the desire to be "ahead of the whole planet" at all costs, still hurt!) the first stage bench tests were abandoned. "If the rocket will fly, and instead of the second and third stages put pieces of iron, with what eyes will I come out of the bunker?" — said Korolev. In short, they decided to test the rocket all at once. But "Kord" did not meet expectations, it did not provide the required synchronicity, did not have time to turn off the defective engine, which affected the entire H1 system.

Again, over the ocean, the stages were worked out sequentially, and in the end it turned out to be much more reliable — the Saturn started from the first approach. Of the $ 25 billion spent on the Apollo project, more than $ 18 billion was spent on a ground-based test base and on testing the design in ground conditions. By the way, when N. S. Khrushchev released the first 500 million rubles for the lunar program, the head of the ground-based test complex L. A. Voskresensky said that to solve the problem, it is necessary to receive ten times more funds. S. P. Korolev replied that if he named such a huge sum to the government, the work would be stopped altogether.

Creating engines for the H1, the designers neglected another previously strictly observed rule. At that time, the reliability of the LRE was checked by one of two methods. At the first stage, each engine was tested on a bench and, after eliminating defects, installed on the product. In the second method, only selected engines from the series were tested. If the test was successful, the tested engine was written off, and the entire series was accepted without further testing. Starting with Yuri Gagarin's flight, all the rockets were tested using the first method. This time, in an effort to speed up the course of events, they preferred the second way. The situation was aggravated by the fact that, as already mentioned, the entire H1 propulsion system was not previously tested on the ground. The history of creating engines for the H1 is full of drama. One of the main lessons of this story for rocket technology is that even the high reliability of a single engine does not mean the corresponding reliability of the entire propulsion system, which necessarily requires careful ground testing.

Today it is easy to throw a rock at Korolev, but let's not forget that he was not a novice in cosmonautics, he understood the whole risk of refusing bench tests and went to it consciously. The ideology of H1 was determined by two factors: the shortest time frame and scanty funds. Let us recall in this connection the attempt of Korolev, who was not at all deceived about the real balance of power, to excel at least at the intermediate finish...

Flight tests of the H1 rocket began on February 21, 1969. 70 seconds after launch, the flight stopped due to a fire in the tail section of the first stage. On July 3, 1970, during the second launch attempt, a large explosion occurred due to a malfunction of the oxygen pump, which destroyed the launch complex. It took a long time to restore it and prepare a new rocket, and only on July 27, 1971, a new attempt was made. The rocket rose slightly above the ground, but due to the loss of control over the rotation channel, the further flight was disrupted and the launch pad was damaged again. According to one of the test managers, V. A. Dorofeev, such major accidents made a depressing impression on the entire staff. But there was no thought that H1 was doomed, that its defects were chronic. People worked hard, many asked to extend their business trip at the test site, and it was felt that the rocket was "growing up" and success was not far away.

Finally, the fourth launch was on November 23, 1972. All systems of the enchanted first stage, all engines worked normally, the flight lasted 112 seconds, but at the end of the active section in the tail section there was a malfunction, and the flight stopped. Nevertheless, the designers and all the services of the cosmodrome were unspeakably happy. Now it's clear-half a step to victory.

- 8 -

— Even if you are present at the Soyuz launches dozens of times, you can't help but worry, — recalls one of Korolev's oldest assistants, corresponding member of the USSR Academy of Sciences B. E. Chertok, who was appointed technical director of the last launch. — But the picture of the launch of H1 is not comparable to anything else. The whole neighborhood is shaken, a barrage of fire — only an insensitive person can remain calm at these moments. All thoughts and feelings are tense. I just want to help the rocket:

"Go, go higher, fly up." It seems that all the neurons of the brain are working hard, trying to guess what is happening inside the rocket. But just as no surgeon can know what is going on in the patient's body during the operation, so we were not allowed to accurately predict the behavior of the rocket after the refusal of bench tests.

Four or five test launches during tests of rocket and space technology are common. Even the "seven" (R-7), incommensurable in complexity with the H1, flew only from the fourth time. How, for example, was it possible to foresee a fundamentally new effect - resistance to calculated acceleration due to bottom pressure, which disrupted the third launch? Now it is taken into account in the design of each rocket. The next two vehicles were already ready for launch in the Baikonur assembly and testing building. In August 1974, the fifth start was to take place, and at the end of the year — the sixth. The sixth, and according to the designers, the last one before the H1 launch vehicle was put into operation. Even the most cautious minds called 1976 as the deadline when the new machine will be fully debugged.

It was a complete surprise for everyone when work on the H1 was first frozen, and after the change in May 1974 of the chief designer-V. P. Glushko was appointed instead of V. P. Mishin-and completely stopped. On the first day, the new head of the Royal Design Bureau declared H1 a mistake, said that he came "not with an empty briefcase" and proposed a new concept, which in more than ten years led to the creation of a reusable Buran spacecraft and an Energia launch vehicle with almost the same power as the rejected H1. Without any doubt, we can be proud of both Buran and Energia, but isn't it a shame to write off an almost finished car to the landfill? However, the new chief designer V. P. Glushko did not have any warm feelings for the H1, because, as we remember, he was initially against this project. And then there's "holding out" on someone else's car — you won't earn fame on it.

"Incompleteness" has become a common occurrence in many areas of the national economy, and this misfortune has not spared cosmonautics. Designers who visited Baikonur in the late 70s still painfully recall the once swarming people and now abandoned cyclopean bulk of the launch and installation and testing facilities H1. From their stories, one can imagine that the picture somewhat resembled Tarkovsky's "zone". The billions spent went into the sand, and it turned out to be possible to close work on the largest project without a thorough analysis, without taking into account the opinion of specialists — it was enough to use the subjective judgment of individuals.

However, emotions are unreliable. Maybe it was really impossible to "finish" H1 and the work reached a dead end? Just one fact: in 1976, N. D. Kuznetsov, obviously concerned about the prestige of his design Bureau, conducted bench tests of the engine for the H1. The engine worked without stopping... 14 thousand seconds, while it took only 114 — 140 seconds to launch the rocket into the required orbit.

This is the end of the history of the H1 launch vehicle. The last," swan " song of the Korolev turned out to be unsung. Of course, it would be unfair to write off the entire N1 at a loss. Factory equipment, assembly and testing facilities, and launch complexes were later used for Energia. No doubt, the experience of designing and "finishing" a powerful rocket was also useful — Energia, in fact, started from the first time. In addition, some stages of the "rocket train" still successfully run in separate "trailers", delivering" Salyuts"," Probes " to orbit, and helping other spacecraft. A lot of engineering findings found in the process of working on H1 are reliably registered in the arsenal of rocket science.

Still, let's not sugar-coat the pill. The termination of work on H1 deprived our cosmonautics industry of its natural, progressive development, and disrupted Korolev's general line of moving the industry forward. Some experts believe that it is since then that the space industry has been living without a long-term program, content with scattered projects. Was it not at that moment that the first grounds were laid for the widespread critical campaign that has recently unfolded against cosmonautics? In technology, as in living nature, there are unshakable laws of evolution, which no one can break without consequences. In fact, for 30 years we have been limited to a payload of 20 tons, so what significant impact can we talk about from orbital stations? A powerful launch vehicle, the need for which Korolev brilliantly foresaw, opened up the widest prospects for cosmonautics: from the creation of large orbital complexes to the launch of automatic vehicles to other planets.

And in the early 70s, there were specialists who understood that the closure of the H1 topic would adversely affect our cosmonautics. V. P. Mishin went to high offices, B. A. Dorofeev wrote letters to the XXV Congress of the CPSU, V. N. Chelomey saw the prospect of using Kuznetsov engines on their cars, and a number of specialists asked for "small things" — to allow testing of at least two ready-made missiles in the ocean... It was all useless, and other opinions were lost in the silence of the high offices. The fate of H1 was not decided by specialists — the logic of scientific development was dictated by political leaders. So it was with the approval of the lunar project and, to a greater extent, with its closure. Not a single meeting of the Academic Council, not a single meeting with specialists, not a single meeting of the Council of Chief Designers... What influenced the fate of H1? In any case, considerations are far removed from the interests of science, from the true interests of the country. In the absence of an official version, I will express my assumptions. Work on H1 was delayed for a number of reasons, and those responsible for cosmonautics (first of all D. F. Ustinov) made promises for so long, first to N. S. Khrushchev, then to L. I. Brezhnev, that they were already beginning to feel uneasy about their own situation. It was safer to shift the responsibility onto someone else's shoulders, to declare H1 a mistake. The President of the USSR Academy of Sciences, M. V. Keldysh, one of Korolev's brightest associates, who together with him was burning with the idea of creating the H1, was seriously and terminally ill at that time and could no longer find the purely physical strength to resist the attacks on the rocket.

- 9 -

In addition, the Americans had already successfully landed on the moon six times. It was finally clear that we were behind them. Ideologists who thought they were protecting the interests of the state came up with a saving guess: wouldn't it be better to declare the manned exploration of the Moon an unnecessary undertaking, and the fact that we ourselves had been going in the same direction for a long time — to keep it more strictly classified? It is curious in this regard that the first landing of people on the moon was not shown on television only the USSR and China.

Political leaders did not understand that a heavy launch vehicle was needed not only for the moon. Those who were responsible for space exploration could explain this to them, but they were often concerned about something completely different. As a result, a unique Martian program based on a heavy launch vehicle was disrupted. Well, about such a "trifle" as the honest work of thousands of people who gave their best years to H1, they simply did not think. Not only were people not consulted, they didn't even explain anything. It turns out that together with the" guilty "H1 was written off to the "dump" and its builders, many of whom, I am sure, received such a psychological blow that they could not create anything of equal value. But these were the best "royal" shots...

There was a third reason, which probably outweighed all the others. The United States, having completed the Apollo program and last used Saturn 5 to launch the Skylab space station, has begun developing reusable systems. We also completed our lunar program-but with a different result-and once again started chasing. This time we succeeded, made "Buran". But is it good for the cause that the strategy for the development of cosmonautics is now dictated not by the USSR, which gave the world the pioneers of space? It was from that time that we almost for the first time chased after the Americans, repeating their mistakes and not really thinking about the expediency of our own actions. Little by little, copying the American experience became an unkind tradition in other areas, condemning the USSR to the position of forever catching up. With a great delay, voices are now being heard: do you really need reusable systems that are extremely expensive and difficult to operate? But if they are still useful, then H1, as many reputable experts are convinced, could have been adapted to launch a domestic Shuttle into orbit. And then the huge funds spent on the development of Energia would have been saved.

By the way, I don't have any official data on the cost of H1. But V. P. Mishin and B. E. Chertok said that the cost of it for all these years amounted to about 4.5 billion rubles. If you compare it with the US spending on Apollo — 25 billion, then the results of the "moon race" are not surprising. All the more remarkable is the ability of Korolev and his colleagues to make a powerful competitive car out of "nothing".

History does not know the subjunctive mood. What was, was. Still, it is difficult to avoid asking: if Korolev had lived for a few more years, would he have been able to bring H1 to the operational stage? However, this question may not be entirely accurate. The design of the heavy launch vehicle itself contained errors that largely determined the four failed launches. But the mistakes were gradually eliminated and it is more correct to ask: would Korolev have been able to convince the country's leadership of the need to continue working on H1? Sergey Pavlovich had a hypnotic gift of persuasion, he had great authority, but the idea that the Chief Designer was invulnerable is incorrect. It is known how enthusiastic he was about Khrushchev, in whom, apparently, he felt a kindred spirit, and how wary of his successor, who was distinguished by high-ranking incompetence and did as his confidants whispered. However, at the funeral of the Korolev, Leonid Ilyich cried and in the obituary allowed for the first time to name the creator of Soviet rocket technology...

Summing up all the circumstances that thwarted the creation of a powerful Soviet launch vehicle and prevented the implementation of the lunar expedition, one inevitably comes to a sad question. Was the bar set too high? Didn't the complexity of the tasks that had to be solved during the lunar expedition exceed the industrial and technological potential of our economy, which was then entering a prolonged period of stagnation? How bitterly ironic are the stories of participants in those events about how factories and design bureaus almost in full force went to harvest, disrupting all the work schedules for the lunar program. And at the same time, in high offices, formal scolding was arranged: no excuses for lagging, at any cost-by the deadline! And in the end-a space "unfinished", accidents that turned into serious accidents. Attempts by specialists, project managers to explain to officials that it is impossible to work like this, could not change the situation. Therefore, the statements of those skeptics who claim that the implementation of such a grandiose project required not only a fundamentally different level of technology, but also a different economic mechanism, a qualitatively new approach to the management of science, industry, and the whole country are not without reason.

The fate of the failed lunar expedition and the failed H1 rocket, as in the fate of any project of such a grand scale, reflects the painful problems of the entire society. These are excessive politicization of science, substitution of real goals for imaginary ones, voluntarism, lack of collegiality in making responsible decisions, unacceptably high importance of personal relationships between industry leaders, indifference to the fate of" cogs", that is, those people who multiply the power of the state with their own hands. Perhaps the most important thing is the inability to foresee the prospects for the development of science, to look into the future, excessive credulity to other people's experience to the detriment of common sense.

In conclusion, we will add that we may still see analogs of H1 in the sky. The Americans, having flown a lot on the "Shuttle", came to the conclusion that they could not do without heavy disposable rockets in cosmonautics. Recently, NASA considered 12 alternative options for the development of rocket technology — one of them provides for the transformation of the Shuttle into an analog of H1. But just beware, finally, of blind copying. I do not call for automatic restoration of H1, and it is certainly not for journalists to solve this global issue.

...When I visited Baikonur, I often noticed a strange-shaped canopy installed in the park above the dance floor. I recently found out: indeed, there is no such canopy anywhere in the world. It was made by the famous Academician Paton using argon-arc welding with X-ray control. A unique item! Only the canopy was not intended for musicians — it is part of a heavy-duty fuel tank for the H1 launch vehicle. They say they didn't know what to do with it for a long time...

Source: Airbase.ru

Further reads

The Soviet Reach For The Moon by Nicholas L. Johnson (1995)

Dividing the Glory of the Fathers by Sergei Leskov (1993)

Lies and incompetence by Sergei Leskov (1993)