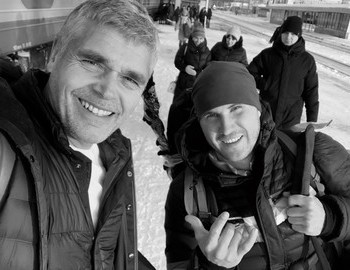

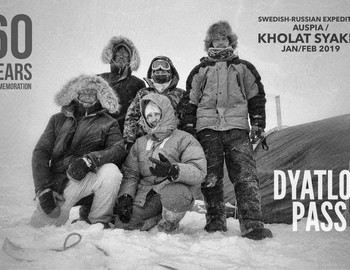

The Swedish-Russian Dyatlov Expedition 2019

The 2019 tour

During the summer in 2018, me and my friend and expedition partner Andreas Liljegren, started to plan for our Dyatlov Expedition 2019. Andreas had his own personal questions and expectations from such an undertaking. Myself, working as an archaeologist, I naturally came to approach the case through matters that were familiar to me. Even though the Dyatlov accident could be considered somewhat recent for an archaeological undertaking - not the least in the absence of field artefacts - it in many ways shared the same prerequisites. The historical event could perhaps be understood through indirect artefacts and other circumstantial evidence. Of course the local and indigenous people - the Mansi - which lifestyle and history fascinates me, have to be put aside for the moment in order to avoid detours from the main subject. This, even if the Mansi presence intersected with the Dyatlov group and still plays an inseparable part of the region.

1) The characteristic tilting trees along the Lozva river drew attention already in early depictions from the 19th century. In the far right, a hand colored print of the local Mansi people of the region. Photo: Richard Holmgren

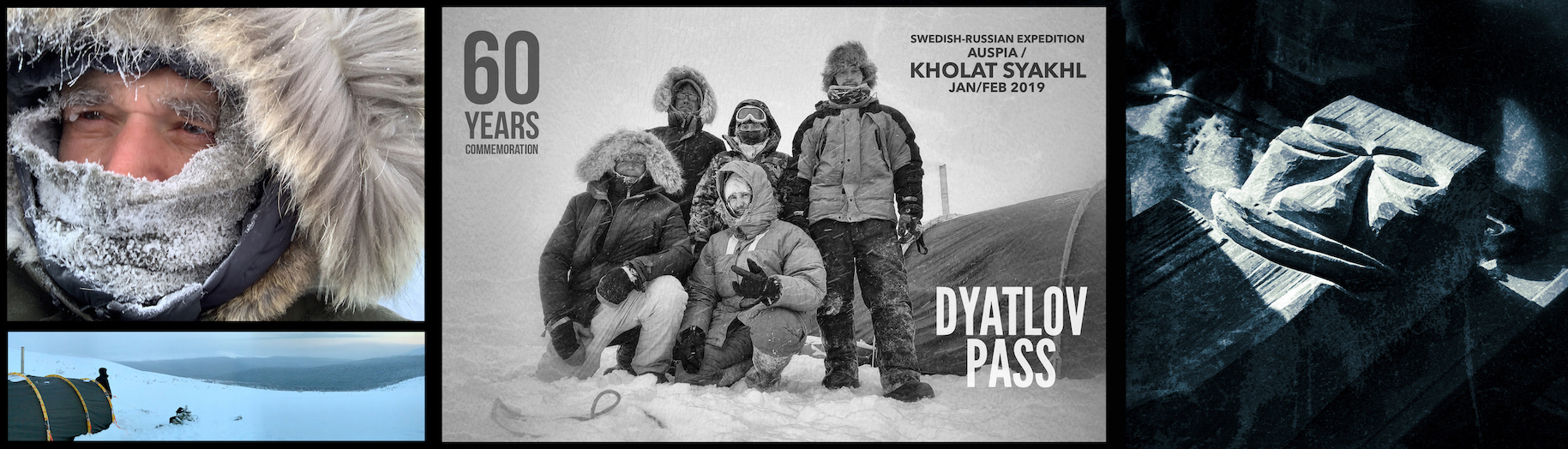

Our approach to the Northern Ural and the Dyatlov pass had two main purposes. Firstly, we wanted to come as close as possible to the historical event by experiencing night camps during the same days of the year as the group in question – this in a tent with a stove, including at least one night on the slope of Kholat Syakhl. Before getting to the position on the mountain we also wanted, likewise to the group in 1959, try to ski through the Auspiya valley in pristine snow and to set up camps in the estimated positions of 1959. In experiencing the same preconditions, we hoped to get a sober idea of what the group went through before their last night. With unthought of details, we could then apply those to our personal theories. Secondly, the reason we went to the region during a week in early 2019 - the transition between January and February, was a kind of homage to the events of 1959 and the 60-years anniversary of the groups passing.

2) The place of an ex-labour camp “2nd Northern”, during the Dyatlov tour, compared to a photo from today. It was here that the group departed from their tenth group member, Yuri Yudin. The photo depicts Z. Kolmogorova taking farewell of Yuri, with Sasha looking over his shoulder. Photos: Dyatlov Foundation / Richard Holmgren

Through the Auspiya valley, southeast of the pass, we were in total four people – me, Andreas Liljegren and our experienced Russian colleagues, Ekaterina Zimina and Artem Domogirov from Yekaterinburg. They were likewise eager to experience parts of the Auspiya route and camping at the specific places of the Dyatlov group, such as the slope of Kholat Syakhl. They met our anticipations greatly and provided us with tent, stove and other larger camping equipment – but most of all they found our hearts through their great strength and extremely joyful humor and spirit. The hardest to deal with during the trip was undoubtedly skiing through pristine snow with backpacks. Unlike the group in 1959 we had half of our equipment filled into individual sledges. We believed that this would ease the weight from the skis and thus prevent us from sinking too deep into the snow - which fortunately also became the case. We know that the Dyatlov group occasionally used the trails of the Mansi hunters, but also that they shifted their front-skier, who without backpack made tracks and later moved to a last-in-line position. In any case we had a hard time keeping up with the Dyatlov pace. For us it was an impossible task and considering that we only skied during one fourth of their total planned time-route, yet a remaining mystery surrounding the Dyatlov group must undoubtedly be their exceptional stamina.

3) Expedition team member, Artem Domogirov, pushing through pristine snow in the Auspiya valley. Photo: Richard Holmgren

The second heaviest task regarded the low temperatures in general. As Swedes we are not completely unexperienced with cold weather, but the brutal temperatures around the pass could be really challenging. With temperatures below 50 degrees Celsius at the day of arrival to Vizhay and additionally on the day after having left the area, we were fortunate. We “only” had to endure minus 43 degrees Celsius during the night in the pass – this on the site where the Dyatlov group pitched their tent their last night. In the Auspiya valley the temperature fluctuated between minus 20 and 35 degrees Celsius, with an average temperature of around minus 25 during the days and slightly below minus 30 during the nights. As Andreas and I are heavy drinkers (water), it was hard to get sufficient with liquid. Water in bottles freezes quite fast, despite continuous movement and a cup of tea didn’t always satisfy our needs in the same way. Along the Auspiya river it was easy to puncture the ice near the shoreline. In fact, sometimes the ice was so thin due to the underlying movement of the water, that it was a danger to use the open river for skiing. This was also noticed by the group in 1959.

4) The author, Richard Holmgren, wondering how he ended up here. Photo: Andreas Liljegren

Other than the issue of drinking water, the cold temperatures affected the food and the snacks in the backpacks. Without cooking, almost nothing could be eaten during the trip - such as the brought about dried fruits, which were frozen into lumps of ice. Certain zippers also malfunctioned and the soft but strong G-1000 cloth in our jackets and trousers (the classic Swedish brand of Fjällräven) simply turned into crispbread. The sleeping bags that could endure temperatures to minus 35 degrees Celsius, delivered satisfactory. The only problem in this case involved the practice of packing down the daily clothing into the sleeping bags during the nights in order to have warm clothes in the morning. This prevented warm air to circulate inside and created far too cold sleeping bags. Thus, this lead to an uneasy feeling when crawling out of the sleeping bag, having to put certain cold clothes on before the morning routines. The stove provided good warmth during the nights – but mainly to a level of not making equipment and food to freeze. In a photograph from 1959, Slobodin can be seen posing with a burnt jacket. Obviously it was left to close to their stove. When we ourselves were drying any wet clothes in the tent, we tried to do so during the evening hours while still awake. A pile of freshly cut firewood was furthermore stacked around our stove in order to both dry the wood and to prevent things like sleeping bags to accidentally make contact with the heater during the night.

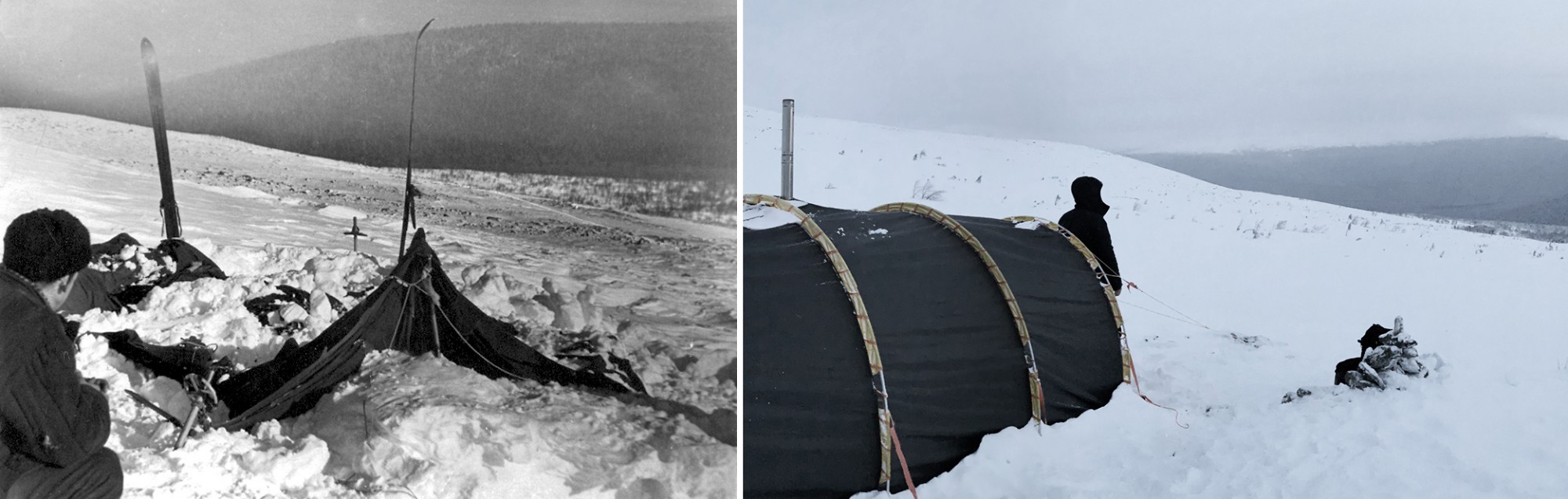

5) The Dyatlov group’s tent with its specially constructed stove – crafted by Igor Dyatlov himself. To the right our own tent with its stove in action, here seen halfway into the Auspiya valley, somewhere afore the groups Jan 30 camp in 1959. Photos: Dyatlov Foundation / Richard Holmgren

Many people have asked us, predominantly in popular media, how the night on the pass underwent and if “we were scared”. Well, the one who reads the concluding theory below, of what I really think killed the group, he or she will understand that we really had a big reason to be frightened. However, difficult skiing through the day, pitching of the tent, cooking, sawing and chopping wood, made each evening into a sleeping pill itself. Before the trip we actually asked ourselves how it would be possible to spend 14 hour inside a tent – we can assure the reader that we never touched any of the game boards brought along. Only some vodka.

6) A view from the Dyatlov pass looking down over the frozen western part of the Auspiya valley. Photo: Richard Holmgren

Foreword and remarks on the new theory

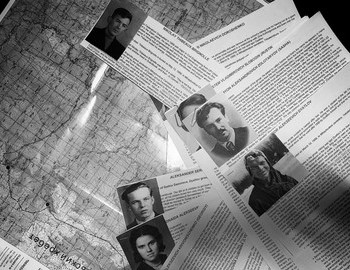

The new theory to the causes of the accident at the Dyatlov pass in 1959, put forward below, assumes that the reader is already acquainted with the story at large, the events in the pass, its various theories, group composition and other details. For the Swedish reading audience, a summary of the Dyatlov pass incident and the planning of our trip can be found here. If not - an excellent source of information is the comprehensive website containing almost everything surrounding the Dyatlov pass, found at Dyatlovpass.com. There are also some well researched books out there presenting various theories, the personalities of the group and the pass itself - this sometimes with great commitment and sensitivity to the people involved. Saying this, I must add that I never understood TV documentaries, podcasts and other articles putting emphasize in cryptozoology and flying saucers as alternative explanations to the group's death. Think again – if an extraterrestrial civilization appeared in the pass or if a surviving ape from the past is roaming the taiga, then the mystery of the Dyatlov accident fades in comparison. This is furthermore not the kind of respect the Dyatlov group deserves - or their surviving relatives for that matter. Thus, I believe that a rational approach is the best way to pay respect to the members of the group – all of them personalities that likely wanted nothing else than letting us know how they might have spent their last hours in life. This with dignity.

My outline to the theory of the Dyatlov pass incident is rather pragmatic and will probably disappoint those seeking a cryptic mystery. By comparing the events with a case from my home country Sweden, I think that a new approach with interesting details of comparison could be very illuminating. In this context I want to apologize to the people having presented a similar theory up to date – a presentation that I might have missed, not the least among all excellent Russian productions that are hidden to me behind picturesque Cyrillic letters.

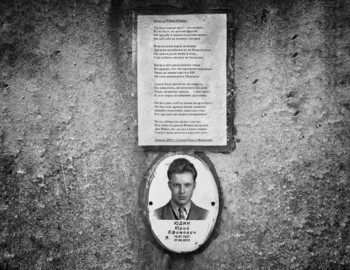

7) Ekaterina Zimina visiting the graves of the Dyatlov group at the Mikhailovskoe cemetery in Yekaterinburg. To the far right the grave of Z. Kolmogorova decorated with flowers. Photo: Richard Holmgren

7) Ekaterina Zimina visiting the graves of the Dyatlov group at the Mikhailovskoe cemetery in Yekaterinburg. To the far right the grave of Z. Kolmogorova decorated with flowers. Photo: Richard Holmgren

A new theory on the Dyatlov pass incident - an outline

The theory is based on the experiences from our Dyatlov expedition during Jan/Feb 2019 and the accident that occured at the Anaris mountains in Sweden 1978.

Almost twenty years after the accident in the Dyatlov pass, an interesting parallel occurred in north-central Sweden. More than any other theory on the Dyatlov pass incident, that I have taken part of, I believe the Swedish disaster can hold an answer to the now 60 year old mystery. In Sweden the tragedy which killed eight people, is often referred to as the “Anarisolyckan”, which in Swedish can be translated to “the accident at Anaris”. The latter place is the name of a rolling terrain that bear much resemblance to the passes south of Otorten in the Urals.

8) The snow covered mountains of Anaris in Sweden

So, what was it then that happened at Anaris that unfortunate day of February the 24th in 1978? Actually and as an ironical coincidence, the Anaris accident likewise involved nine people, two young women and seven men of which one of the latter barely survived. Initially, during the daytime, the Anaris skiing trip included only six people. They had brought with them food for a day’s tour, but also rescue packs in the form of wind sacks, radio equipment and shovels. The first stage of their skiing tour involved an undertaking uphill of about three kilometers - this over a ridge which made them sweaty and tired. It very much resembled the Dyatlov-group’s approach from the Auspiya valley and up to the ridge next west of the now named Dyatlov pass. The Swedish group were probably not nearly as fit as the Russian team of nine, but we currently don’t know if some in the Dyatlov group got sweaty. Considering that this was the Dyatlov group's first larger uphill challenge during their tour, carrying heavy backpacks alongside a possible time pressure to reach beyond the pass, the question might be pertinent - considering details such as their light dressing in the tent during the last evening. As well acknowledged, the combination of extremely cold environments and sweaty clothes, can be devastating in keeping the body warm and fit.

9) Andreas Liljegren taking a well deserved break from tough skiing through the woods. Photo: Richard Holmgren

When the Anaris-group started the trip, they encountered an outside temperature of around minus 15 degrees Celsius (5 degrees Fahrenheit) with a wind speed of around 6 m/s. This particular day the wind accelerated and the physical situation of the group gradually affected their condition. The weather then unexpectedly changed to the worse and an enjoyable skiing tour rapidly turned into an tormented state of survival. Soon the temperature dropped even further, but the situation really turned devastating due to the sudden acceleration of the wind - this with wind speeds up to at least 20 m/s. The cooling effect was then around minus 50 degrees Celsius (-58 degrees Fahrenheit). The group hastily tried to seek protection – which they did in an immediate dug out ditch along the trail. The shelter that was only 0,8 meters in depth (c. 2.5 feet), had its top cover repeatedly blown off.

Yet another three people, also surprised by the sudden storm, tried to join the shelter. In all there were now nine people with four wind sacks and sleeping bags, fighting for survival. However, the sacks and bags were never used since they failed to open any of their backpacks alongside an overall chaotic situation. The last joining people that requested shelter together with the other six, repeatedly tried to fix the constantly failing uppermost part of the bivouac, this from the outside - but had to give up. Unable to fit inside the crowded and by snow blocked entrance, they eventually wandered out apathetic in the storm. Only one of them survived since he was in constant movement and was fortunate to be saved by two people later on - although losing all his extremities. Inevitably and as we shall see, I believe that this last portion of the event can give us an idea of what Slobodin, Kolmogorova and Dyatlov went through after being unable to save their friends. This with one big exception though - the Dyatlov pass was far from any helping hands. Let us return to this later.

10) The chilling temperatures on the 1st of February 2019, between the Dyatlov pass and Kholat Syakhl. Photo: Richard Holmgren

Learning from the event in Anaris, the decision to seek shelter was made way to late and their hastily constructed bivouac was much too shallow. If only they had dug 15 meters further away they would have found a sufficient snow depth of about five meters. For the Dyatlov group the snow depth of their made bivouac(s) was well chosen considering the forceful conditions, but as we shall see, with another devastating effect. The Anaris group’s warming equipment stayed in their backpacks which were not reachable due to their numb hands. Their clothing was sufficient, but the sudden compelling force at Anaris was far greater. The rescuers arriving to the scene, described the place as the worst they had ever encountered. The snow was all covered with blood from open wounds as a result of digging in the snow with frozen hands.

Then - what kind of sudden "blizzard" killed the Anaris group?

11) One of the last photos taken by the Dyatlov group - approaching their final campsite on Kholat Syakhl. Strong wind is already present. Photo: Dyatlov foundation

11) One of the last photos taken by the Dyatlov group - approaching their final campsite on Kholat Syakhl. Strong wind is already present. Photo: Dyatlov foundation

The understanding of the sudden strong winds that surprised and killed the people at Anaris, can be defined as a katabatic wind (from the Greek's katabatikos, meaning "descending"). It is a wind that by gravity carries air of higher density down a slope. This specific wind is also known as a fall wind, a downslope wind or a gravity wind. The katabatic wind can occur over glacier or mountain areas as the air is cooled and thus increases in density. When the air is set in motion and begins to run down along a gradient, very strong wind speeds can occur. A Swedish wind record is for example 81 m/s which was documented on December 20, 1992 at the Tarfala research station. According to estimates in 1959, the temperature that the Dyatlov group experienced in the late afternoon and in the evening on the first of February, was between minus 25 and 30 degrees Celsius. A sudden change from strong winds into a fall wind on the slope of Kholat Syakhl, could reasonably have reached wind speeds of about 25 m/s. The cooling effect would then have been around minus 65 degrees Celsius, or minus 85 degrees Fahrenheit. In a brief period of time such temperatures can be deadly, let alone the wind that in itself would make it hard to stand upright.

12) Looking down from the ridge near the Dyatlov pass over the slopes leading to the western area of the Auspiya valley. It was there that the Dyatlov group started to experience a steady airstream - compared to a jet engine. It is likely somewhere in this upper area tha the photo above was taken. Photo: Richard Holmgren

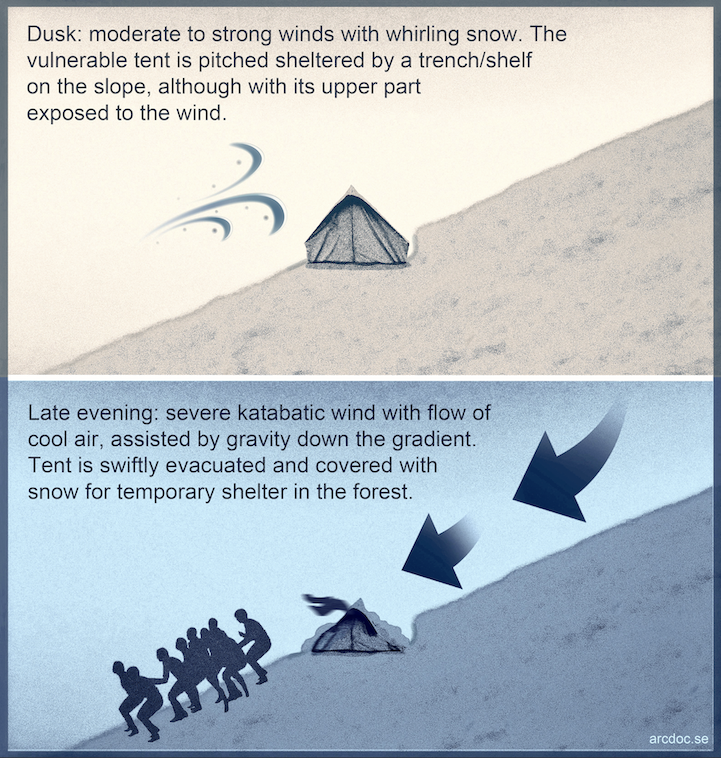

Let us now apply the scenario of a katabatic wind affecting the Dyatlov hikers in 1959. From their group diary we know that around noon, on the day before their last campsite on the slopes of Kholat Syakhl, the wind escalated. We also know that the wind was compared to a “blow fryer” – according the group it was associated with the steady airstream of a jet engine. A remark in the diary also clarifies that snow was whirling in the air but not coming from any clouds since the sky was blue. Obviously and as presumed by the group, the snow came from the trees in the valley below, blowing its way up along the peaks. In line with the local topography and one of the last entries in the group diary, the wind was blowing from the west and as such pushed its way up the “back” of Kholat Syakhl. This had a potential to turn dangerous since the air interacting with the highlands was cooled – thus becoming denser than the air at the same elevation but away from the slope. A large-scale gravity wind, descending too fast to warm up, could then have exhibited itself as an extremely strong wind flowing downhill and replacing the gap of the warmer air masses. In the middle of this scenario stood a very vulnerable tent.

In other words, the conditions described in the group’s last entries had the prerequisites for the buildup of a katabatic wind with devastating effects. Little did they know - and little are we still today prepared for any analogous and local occurrences. These small changes in air pressure are barely noticeable on the meteorologists' weather maps and could still easily lead to the devastating effects that we have seen in the Anaris accident - for that matter, even during our own night on the slopes of Kholat Syakhl. We packed down our tent the 2nd of February 2019 during the 60 years anniversary of the Dyatlov event, but later learned from EMERCOM (Ministry of Emergency Situations in Russia) that during the upcoming night the temperature fell from our minus 43 degrees Celsius down to near minus 50. This low temperature was furthermore complemented by an immense storm - although not being a katabatic wind, it still would have had a force enough to put us in an extremely hazardous situation.

13) The last views of the Dyatlov group alive. The winds on Kholat Syakhl are still strong, but seemingly under control. Photo: Unknown

We know for a fact, from the series of last photos taken by the Dyatlov group, that their weather conditions worsened. On the photograph showing them mounting the tent for the last time, winds are obviously battering the slopes of Kholat Syakhl, creating snow covered clothing and poor visibility. Considering the seemingly dim light (?), we can assume that they were somewhat late in pitching their tent – perhaps due to a rather exhausting climb, but still felt in control regardless of the weather. After all – winds on the slope of Kholat Syakhl are more or less ever present during this time of the year. Igor Dyatlov would have been well acquainted with this, since he spent time in the area the previous year. What they didn’t anticipate during the evening of February 1st, was that a moderate wind with stronger gusts could rather swiftly turn into 25 m/s – or even much above that.

Thus, my theory to the group´s death is based on the sudden event of a katabatic wind. Presumably the wind was already significant but rather stable during the late afternoon and early evening. This gave the group time to settle, remove any wet clothes and eat leftovers - since the stove was stowed away, probably due to lack of enough firewood which was not present on the slopes. Their shoes were nicely stacked against one side of the tent and their sleeping bags placed in a row - close to each other to keep warm. There wouldn’t have been an option to sleep in larger gaps due the size of the tent. The tent was a converted single tent that was stitched together with a second length of canvas. We can for example learn from their journals that the construction needed overall and constant small repairs. Even though the tent never seemed to have been ripped apart in its seams, it’s construction must have been a constant reminder of its vulnerability in the event of a storm. Since the tent was fastened with standing skis (?), rather than being anchored into the ground or attached to heavy stones on the slope, we can assume that the wind at the time of pitching wasn’t too strong. However, such solution required even faster actions if the wind somehow accelerated and became threatening to the tent.

One thing that I want to mention in this circumstance, regards the angle of the pitched Dyatlov tent. This is not forwarded as any criticism to the professional hikers, but something that might have helped them temporarily under any possible turbulent event involving strong winds. Obviously they raised their tent laterally on the slope. Aware of the dangers of conceivable falling winds, we instead pitched the tent with the least largest area facing the gradient (photo no. 15). This is not a wise choice for creating a suitable sleeping surface, but vital to succumb impending winds from above.

14) Fighting an outside temperature of -43 degrees Celsius from Inside our tent on the slope of Kholat Sayakhl. The photo was taken during the late evening, February the 1st - perhaps at the time when heavy falling winds started to roll down the slopes exactly 60 years ago. Photo: Richard Holmgren

14) Fighting an outside temperature of -43 degrees Celsius from Inside our tent on the slope of Kholat Sayakhl. The photo was taken during the late evening, February the 1st - perhaps at the time when heavy falling winds started to roll down the slopes exactly 60 years ago. Photo: Richard Holmgren

One thing that I want to mention in this circumstance, regards the angle of the pitched Dyatlov tent. This is not forwarded as any criticism to the professional hikers, but something that might have helped them temporarily under any possible turbulent event involving strong winds. Obviously they raised their tent laterally on the slope. Aware of the dangers of conceivable falling winds, we instead pitched the tent with the least largest area facing the gradient (see photos below). This is not a wise choice for creating a suitable sleeping surface, but vital to succumb impending winds from above.

What happens next on the slope could perhaps be described as a rumbling noise of a wind rapidly escalating from above. In the next minute or even seconds, the wind got so strong that any tent would have blown away or into pieces. Now, any person that haven’t experienced falling winds, would probably argue that no wind in the world can blow up this fast and with such a great force, that there would at least be time to put on clothes or shoes. They´re wrong. Any such wind as described above, would completely take anyone off guard - such in the case of Anaris with its following consequences. I have personally experienced weaker but similar circumstances on the glacier of Mt Ararat some years ago. The canvas of my anorak almost teared apart because of the ripping effect caused by the wind. The large canvas of the Dyatlov tent would have started to flutter in an exceptionally violent self-destructing way, much so - that the only way to save it would be to cut it open from the inside in order to rush outside for measures of saving it. This, unless it accidentally teared itself apart by any item pushed against the canvas to keep it stretched. In any case, there wouldn't have been any time to dress in the dark or to unbutton the tent before exiting. The only way to save the situation would be to throw oneself out and quickly cover the canvas along with its content with the surrounding snow masses - this in order to prevent the tent with its content to sail away and to disperse in the dark. This would explain the snow that was covering the central part of the tent when found. Again, from the photos available there is simply no traces of an avalanche in the surrounding snow pattern. The gradient of Kholat Syakhl is furthermore far to gentle and the distance to the top much too short to create momentum. I had the perfect occasion to study this long gnawing question of mine during our stay on the slope.

In the case of the Dyatlov group and as indicated, a flashlight was left to shine on top of the snow pile – likely in order for the group to reposess the tent as soon as the sudden and chaotic situation got under control. The best they could hope for was that the Chinese flashlight would stay in place albeit the strong wind, this due to its relatively heavy and small size. One of the photos showing the abandoned tent from the west, clearly demonstrates patterns of heavily wind swept snow - where vortexes of wind have hollowed out scoop-shaped cavities. Snow affected by strong wind is also evident in the photos of the three bodies that were buried in the lower part of the slope. Densely packed snow was here surrounding them in tight layers. If examined correctly, this would also indicate that these three people, Kolmogorova, Slobodin and Dyatlov died when the wind was still battering from above. Perhaps the branch that Igor Dyatlov was still hanging on to when found, was a result of such conditions?

15) The Dyatlov group's tent was found the 26th of February partly covered by snow. To the right Andreas Liljegren is seen standing outside our tent, near the position of the 1959 campsite. Photos: Dyatlov Foundation / Richard Holmgren

15) The Dyatlov group's tent was found the 26th of February partly covered by snow. To the right Andreas Liljegren is seen standing outside our tent, near the position of the 1959 campsite. Photos: Dyatlov Foundation / Richard Holmgren

Crawling back under the snow covered tent, if possible at all due to the conditions involving a gravity wind, wouldn’t have helped them - which they wisely and obviously realized. Yes, the tent would have been better secured with the group inside, but the cooling effect under a gravity wind would eventually have killed them. Furthermore the torn tent was already made unsuitable for this option. In fact - it was exactly this that killed the Anaris group, where the only survivor escaping the shelter, was the only survivor. He was in constant movement and ventured elsewhere, while the rest froze to death.

I would argue that the group likely acted in the best possible way under the prevailing circumstances - nothing irrational at all and totally in line with their experience and professionality. Running out in their socks or in their valenki, was obviously insufficient in the long run, but a wise decision considering the explosive event. With the extremely low temperatures at hand, their socks wouldn’t immediately turn wet as long as they moved quickly down to the forest to seek a temporary shelter. The people wearing valenki (felt boots), like the ones found on Zolotaryov, would have last much longer. That Dyatlov and his friends followed the natural groove on the slope, all the way down to the edge and into the woodland, points to the fact that they were well aware of the fastest way to an alternative place of "safety". Probably and as their footsteps vaguely demonstrate, they went as tight as possible in order to keep together – sometimes venturing apart, likely due to extremely strong winds battering their shoulders. I would even suggest that if the gusts exceeded 25-30 m/s (or much more), some of them could occasionally even have tumbled down exposed parts of the incline. The stone belt below the tent would even have had the potential to cause fractures and open wounds. Projectile-like flakes of ice from the snow cover is another dangerous effect of such forceful winds - although, no exact information on the conditions of the snow during the time is at hand. The broken ribs of Zolotaryov and Dubinina is a different case though. We shall return to that shortly.

After arriving to the forest and eventually into the area of the large cedar tree, the winds would have still been very strong, but the best possible shelter for waiting out the ordeal away from the slope. I think these actions are important, because many would argue that fleeing from the tent and warm equipment in such conditions, would mean certain death. In line with their outdoor experiences I'm sure they knew that such winds were unfortunate and rare, but hopefully wouldn't last all night. Their tent and equipment, if still in place, would be within grasp as long as they stayed alive elsewhere. It is important to note though that as time passed, irrational behaviour should be expected. In this instance it might explain peculiarities in decisions and behaviour. Hypothermia means that the body core temperature sinks below 35 degrees Celsius. This usually gives symptoms of fatigue, impaired coordination ability, confusion and hallucinations. Eventually, apathy usually kicks in. With a body temperature of around 30 degrees Celsius, most become unconscious.

16) Pedestal footprints preserved on the lower part of the slope. Photo: Dyatlov Foundation

16) Pedestal footprints preserved on the lower part of the slope. Photo: Dyatlov Foundation

When touching upon the footprints left in the snow, there are reports of prints mentioned by the first rescuers arriving to the abandoned tent. These rescuers belonged to the Slobtsov group. One of these UPI-students, Yuri Koptelov, reported footprints as if people were positioned shoulder to shoulder. Depending on the exact location of these prints, it could perhaps reveal the last actions of the group before leaving the tent - how a hurried team spread out alongside the tent in order to effectively bury the wind battered canvas with snow? The preserved footprints on the slope are in large a bit peculiar, but so is a gravity wind. In some places prints are preserved and in some cases gone with the wind. The pedestal prints could be a result of a warm foot creating a harder icy surfuce on the snow - or simply the compressing power from the body weight, where the wind later cleaned the surrounding area (photo no. 16). Obviously, this would have been very effective in strong winds as long as the occurrence was momentary. How warm any foot needed to be, if at all, is very hard say. The perhaps best example of a warm body having melted the snow is the layer found beneath Slobodin which shows that his slowly decreasing body temperature affected the snow below him.

The footprints seen near the tent were on the other hand reported as hollowed. In this case the laying tent could perhaps have steered away most of the wind - this protected by the snow dugout that also sheltered the folded canvas. I would suggest that if the prints were preserved or not, was highly random and that the wind vortexes affected various spots rather unsystematically. Again, the uneven and scooped surface of the snow is very evident in the photo next below (no. 17). Therefore I would like to make a statement to the contrary - that if the weather would have been calm, then any appearing and suddenly disappearing footprints would really have posed a problem.

17) A scattered search team seen below clear patterns of heavily wind swept snow in the direction of the abandoned tent. Photo: Dyatlov Foundation.

The next series of important events are harder to fully comprehend, but likely the experienced group purposely split apart temporarily for survival procedures in the forest. As long as they were in constant movement, the better. While Doroshenko and Krivonischenko took responsibility for making a fire, the others started to dig out two bivouacs, one which was retrieved empty in May and likely meant for Slobodin, Dyatlov and Kolmogorova (photo below). The other bivouac that was retrieved on May 5th was less evident, but contained the four lastly recovered bodies. The young men at the fire must have struggled hard to get a fire going, which was also evident from their unsuccessful attempts. The two men must have fought the worst since the making of a bonfire (as a backup to the bivouac solution) would have been a tremendous challenge in the cold strong wind. In the end - exhausted and looking for a last solution, perhaps they tried to climb the cedar with frozen limbs in trying to get a glimpse of the tent with its glowing flashlight. Was perchance the tent still in position? Possibly it was the courageous Doroshenko himself, as the tallest member in the group, that climbed the tree. This must have been a real tough attempt considering stun hands and feet. A wound in his armpit is perhaps a revealing sign of slipping down against branches. According to the groups dressing sequences and the use of Doroshenko’s and Krivonischenko’s clothing, we must assume that they died first. The others eventually managed to get the two bivouacs ready for use.

Studying the body positions of Kolevatov, Zolotaryov and Thibeaux-Brignolle, it seems as if they were lying snugly behind each other to keep warm. Zolotaryov even had a pen and a paper in his hands which gives the impression of being rather in control. This is in stark contrast to his massive chest wounds that many believe made him inoperable. The same is to say about Dubinina, laying close but in a different angle. She is the second person having unexplainable and crushing chest wounds. We should remember though that she had Krivonischenko’s trousers wrapped around her feet. As in the case of Zolotaryov, these actions does not rhyme with deadly wounds caused early during the ongoing events. I would rather suggest that a bivouac housing the four people, collapsed and trapped them inside. Perhaps the position of Dubinini froze her in a position of entering the shelter or that she simply slipped away with the underlying stream during spring from a previous position near Zolotaryov and Thibeaux-Brignolle. No fir bedding was found beneath the four due to the shelters position over the stream. By the 5th of May, such bedding would have vanished from its position, rather to be found downstream.

18) The retrieved empty bivouac, prepared with branches of fir. Photo: Dyatlov Foundation

Needless to mention regarding the four bodies found in the assumed collapsed bivouac, are the missing eyes and a tongue, which should be considered a natural cause of decomposition. In fact, eyes are reported as being still in place by the pathologist, but shriveled into the back of the eye cavities. Possible traces of radioactivity in some clothing, may also be explained through for example Kolevatovs earlier commitments in the industry, where such excesses in the clothing were a likely side effect. I would also suggest that the punctured chests of Zolotaryov and Dubinini were caused by the weight of the collapsing den – that is, a gradual compression and process over time. In the case of Lyuda, it could have been due to her position over a stone shelf and with Sasha taking most of the weight in his central position of the shelter. The autopsy even makes clear that it was hard to estimate if certain wounds were ante- or postmortem. One should also keep in mind that Sasha and Lyuda could have acquired survivable fractures in their chest that eventually led to their symptomatic postmortem compressions when laying below heavy layers of snow. Lyuda for example, like Doroshenko, had wounds in her armpit which could indicate a fall from a tree or similar, which at the same time might have fractured her ribs - later to cause compression of her thorax.

Furthermore, it is often stated that Lyudmila had blood in her stomach and that this would suggest that she was alive when her tongue was injured - or perhaps even removed by any ill-meaning force. This is however not a case of what’s ante- or postmortem, but a result of wishful thinking. The pathologist never wrote that it was blood in her stomach, but simply mentioned the presence of a red substance. This could be anything from her last meal to any other substance finding its way down her throat whilst she was positioned with her face against running water for many days. Furthermore, if it perchance was blood in her stomach, it could be a result of many other circumstances. One shall also remember that hypothermia-related deaths are still among the most difficult cases for postmortem diagnosis in forensic medicine. There are several cases where changes in gastric mucosa have been seen in hypothermia-related deaths. Ulcers and multiple bleedings in the stomach as a result of severe hypothermia are quite normal. Even if the pathologist in the Dyatlov case only mentioned a “red substance,” we can presume that it in fact was blood as a result of hypothermia. Although not as a result of Lyudmila’s tongue being detached while still being alive.

I also want to mention another problematic occurrence that is not raised very often. This regards the damage to some bodies as caused by the searching sticks when punching the snow - probing for the lost members of the group. We know for example that Ludmila’s body tissue was damaged by such sticks, which was not mentioned in the autopsy report. This might be another shortcoming when separating wounds as ante- or postmortem. Usually everything should be accounted for in any pathological report, but the description of her body shows that no difference to the type of wounds was made when analyzed.

Thus, my hypothesis of the subsequent events is that the rest of the team, Slobodin, Dytlov and Kolmogorova never settled in the nearby bivouac for long – that is, in the bivouac that was retrieved empty in May and still prepared with branches of fir (photo no. 18). Perhaps the chocking experience of this potential death trap, collapsing over their friends and with insufficient strength to help out, gave them only one last option - that of trying to get back to the tent. They never succeeded, but knew exactly the direction to the tent. Biting her numb knuckles, Kolmogorova along with her two friends, finally fell asleep from one of natures many sinister occurrences - a somewhat rare but otherwise well documented, katabatic wind.

19) The Village of Vizhay. Sixty years have passed since the terrible events in the Dyatlov pass. Many things have changed - some things stays the same. Photos: Dyatlov Foundation / Richard Holmgren

The conclusions presented here can obviously be broaden much further. But hopefully the ideas can provide a general outline of a perhaps rather rational theory. The series of events can off course be rethought and modified, but my take despite some perchance hastily concluded details, is that the driving "unknown compelling force" was in fact an unforeseen and strong gravity wind. Humbly, I consider this as a straight forward and rather uncomplicated solution to a 60 year long mystery.

Many thanks to my friend and Dyatlov-expedition partner Andreas Liljegren, for input, sober ideas and awakening thoughts. And - a sincere apology to all offended yetis lurking around in the forests of Ural.

Richard Holmgren, February 10 - 2019

ARCDOC, Archaeological Documentation

Link to Richard’s continuously updated webpage:

https://www.arcdoc.se/se/blogg/dyatlov-expedition-new-theory-41712449

20) Many thanks to Vladimir and Vladislav for their great hospitality when repacking in the village of Vizhay. Merits to a great team and kudos to my little Milou for being patient when adventure looms.

20) Many thanks to Vladimir and Vladislav for their great hospitality when repacking in the village of Vizhay. Merits to a great team and kudos to my little Milou for being patient when adventure looms.

21) ... and thanks to the inhabitants of Yekaterinburg for a welcoming stay - what a lovely town and people!

The katabatic wind - in short

What is important to realize regarding falling winds, is that they appear quickly as opposed to a storm. A storm would give you time to dress and secure or dismantle a tent properly. A tent that is not built for extreme winds, would rather swiftly tear to pieces if confronted with falling winds - this unless it was saved in seconds. In the case of the Dyatlov group the only survivable scenario would be to run out, conceal the tent and to wait out the ordeal elsewhere, later to regain the buried equipment. If the event would continue for a longer time or if the outside temperature is far too low, the consequence would be deadly without suitable shelters or helping hands. One fast way to save a tent from disappearing in the wind, would be too cover it with the adjacent snow masses – this in turn sheltered behind an already prepared snow wall/shelf. In fact, collapsing a tent to reduce the chances of wind damage, followed by a shielding of snow to hold the tent down, is expected in such situations. In the event of a katabatic wind, the Dyatlov team acted skillfully by shadowing the steps above. This could in fact explain why the tent was located with a protective snow cover and a flashlight - likely used as a beacon for relocating the position. Such scenario with subsequent outcomes, was presented by the Swedish-Russian Dyatlov Expedition of January/February 2019, as the causes to the incident in 1959. See above.

In the photos taken by the rescue team, clear traces of snow affected by strong wind can be seen pointing towards the tent from the peak of Kholat Syakhl. The actual pattern demonstrates heavily wind swept snow, where vortexes have hollowed out scoop-shaped cavities. These are comparable to so called zastrugi or in Russian, заструги. Extremely high winds would furthermore make it hard to stand upright. Any possible ice sheet or other flying light objects, besides extremely low temperatures generated through the cooling effect, could theoretically create austere body trauma. However, the severe injuries found on the last four recovered bodies should in the case of a katabatic event, be tied to other circumstantial evidence - such as pressure from a collapsed snow shelter and natural decomposition due to three months of exposure in the prevailing environment. The same can be expected from traces of radioactivity in selected clothes, associated to earlier commitment in the industry by members in the group. Possible light phenomena or spheres reported in the sky thereafter, cannot be associated with a katabatic wind. However and with regard to the sky, katabatic winds could indeed explain sudden plane crashes in the region, were falling winds are one of the most unpredictable and dangerous occurrences associated to such ventures.

Richard Holmgren, February 22, 2019

ARCDOC, Archaeological Documentation

The 2019 expedition narrated by Bedtime Stories

Richard Holmgren and Andreas Liljegren, Dyatlov Pass 2019. Illustration: courtesy of Bedtime Stories 2019

The team behind the celebrated YouTube series “Bedtime Stories”, have a real passion for the unexplained. Their productions combine stunning illustrations with well researched and spellbinding narration. In their recent episode “Return to Dead Mountain” (The Dyatlov Pass Incident - Part 3), their video and Podcast depicts our expedition and new theory of 2019. Kudos to a great production team for presenting our effort in this thrilling manner - not the least for being cartoonized, which really felt awarding.

Gallery