The route not traveled

The mystery of Oleg Vavilov's death - the son of the famous Soviet geneticist

Author Taisiya Belousova

A couple of months ago, employees of the Lebedev Physical Institute (LPI) Yuri Vavilov and Boris Altshuler asked me to investigate the death of the eldest son of academician N.I. Vavilov - Oleg, which happened on February 4, 1946 in Dombay and to recognize the ins and outs of a person whom they considered the culprit of this tragedy. According to them, the The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD) introduced into a skiers group from Moscow a mountaineering instructor, a graduate student of the Institute of Philosophy Boris Schneider. He allegedly led an inexperienced Vavilov to dangerous rocks, where he died. In the evening, another participant in the expedition Igor Shafarevich discouraged skiers from looking for the missing comrade. The next day they did not search for the body, and their leader Nemytskiy shamefully fled to Teberda. The All-Union Committee for Physical Culture and Sports (VKFS) addressed the Prosecutor General's Office with a request to bring Schneider and Nemytskiy to criminal responsibility, but whether they were convicted is unknown.

Rokityanskiy’s answers clearly contradicted the documents I studied. What did really happen?

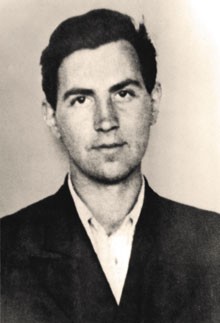

Oleg Nikolaevich Vavilov in 1938

(7.XI.1918 - 4.II.1946)

Having studied the provided archival materials, I wanted to refuse. But then I saw an article "Dropped On Orders From Above", ("MK", 24.VII.2007). O. Boguslavskaya writes about the short but vibrant life of Oleg Vavilov - after graduating from Moscow State University, he was hired at the LPI to work on secret developments during the war, defended his candidate dissertation brilliantly in the 45th, and then the historian Yakov Rokityanskiy answered her questions. He told how Schneider insisted on climbing to Semenov-Bashi. In order not to cause concern in Oleg, he included Sayasov as a student in the group. Later, getting rid of the witness, he advised him to ski on the slopes. And he himself led Oleg to the cliff, where, stealing unnoticed, allegedly hit him in the right temple with an ice ax, and he fell into the abyss. In the hope that the beginning snowfall would hide his tracks, he was in no hurry for help. Schneider was protected from criminal liability by "an organization whose task he so flawlessly carried out".

Nikolay Ivanovich Vavilov with Oleg

(25.XI.1887 – 26.I.1943)

Nikolay Ivanovich Vavilov was a prominent Russian and Soviet agronomist, botanist and geneticist best known for having identified the centers of origin of cultivated plants. He devoted his life to the study and improvement of wheat, corn, and other cereal crops that sustain the global population. Vavilov's work was criticized by Trofim Lysenko, whose anti-Mendelian concepts of plant biology had won favor with Joseph Stalin. As a result, in July 1941 Vavilov was arrested and subsequently sentenced to death on charges of belonging to the anti-Soviet organization "Labor Peasant Party", as well as sabotage and espionage. Although his sentence was commuted to twenty years' imprisonment, he died of starvation in Saratov prison in 1943.

– 2 –

The way to Semenov-Bashi

The initiator of the ski trip to Dombay, members of the Alpsection Volunteer Sport Society "Science" was Professor of Moscow State University V.V. Nemytskiy, organizer and leader of a number of mountain expeditions. 15 people enrolled in the group, but a couple of days before departure the people dropped out, seven remained: Nemytskiy, his wife, professor of Moscow State University N. Bari, associate professor and graduate students of Moscow State University O. Vorobyev, E. Krasilshchikova and Y. Sayasov, doctoral student of the USSR Academy of Sciences I. Shafarevich and O. Vavilov. In order to secure the trip, Nemytskiy included in the group a mountaineering instructor, engineer A. Belyaev. As for Schneider, then, according to the practice of those times, the group needed to be "strengthened" by a member of the CPSU, and so the professor remembered Boris. They had known each other since the pre-war era, and Nemytskiy highly appreciated Boris as a climber and reliable companion. In May of 1945, he applied for the assignment of the All-Union category in mountaineering, and in July-September, at the invitation of the professor, he participated in the first post-war scientific-climbing expedition to the Tien Shan.

According to the testimonies of Belyaev, Krasilshchikova, Vorobyeva and Nemytskiy, someone came up with the idea for a winter ascent to Semenov-Bashi on the train. Vavilov, who had been to the summit twice in the summer, and Sayasov took it "with a bang". Nemytskiy cooled their hot heads with the consideration that for a winter ascent they need to get permission from the VKFS and equipment is necessary. Vavilov and Sayasov never dropped the discussion.

The first two days, skiers (except Belyaev, who fell ill with a bout of malaria) walked around the Dombay glade, visited the Chuchurskiy waterfall. February 2, when the group skied on the slopes of Semenov-Bashi, Vavilov disappeared. He returned to Dombay late at night and said that he had carried out a reconnaissance and under favorable conditions, you can reach on ski the summit ridge of Semenov-Bashi. He was supported by Schneider. Nemytskiy allows Schneider and Vavilov to go to the summit on ski. Sayasov is only allowed to ski on the slopes of Semenov-Bashi. And although Schneider is appointed the leader of the group, Belyaev for some reason tells everything that he knows about the summit, not to him, but to Oleg. On February 3, Schneider, Vavilov and Sayasov spend the night on the upper kosh (summer Caucasus shepherds' camp), and on February 4 at 8 am they leave for Semenov-Bashi.

After climbing 600-700 m (2000-2300 ft), Schneider and Vavilov leave Sayasov to ski, promising to return at 5 pm. According to the latter, "Schneider was not leading the ascent. Vavilov took over his role. Vavilov forbade me to go further when we approached the ridge."

– 3 –

Drama by the big gendarme

After some time, Schneider and Vavilov, leaving their skis, go to the southern buttress of Semenov-Bashi. They tied with a rope and climbed light cliffs for about an hour. To reach the southeastern ridge, you need to go around difficult cliffs along a snowy couloir (a depression on the side of a mountain that widens after going down). But walking in the snow, which is "very soft", is impossible. According to Schneider, "Vavilov insisted on going out onto the rocks. Vavilov was the first, he was much stronger, I didn't feel well bad that day."

By 3 pm the climbers reached the large gendarme (a rocky ledge on the ridge blocking the path). Climbing it, Vavilov saw that further on the cliffs are difficult. During the break they decided to go west. Going down the light cliffs 10-15 m (30-50 ft), Boris caught himself that he had forgotten his ice ax stuck in the snow where he left it during the break. Having warned Vavilov, he untied himself and went back to the gendarme. And on his return he saw that Oleg, having unwound the rope, was walking along the rocks to the west. On the offer of Schneider to tie themselves again, he refused. Schneider began to look for an easier way to climb. Climbing a few meters, he noticed that Oleg had reached difficult icy cliffs and suggested that he went his way. Vavilov tried to do this, but 5-6 m (15-20 ft) before reaching the end of the rocks he slipped. Hearing the rustle, Schneider immediately turned around, and witnessed a horrible sight: "Vavilov first slid one and a half or two feet down, then cried out and, leaning his body away from the rocks, fell on a rocky ledge with his back and then fell down from stone to stone, hitting his head several times. The first blow was at 4 m (13 ft), then at 20-30 m (65-100 ft) down, he fell on a snowy couloir (ed. - a steep, narrow gully on a mountainside) and rolled, turning from side to side about a hundred meters (328 ft). "Having caused an avalanche, by inertia he went away from the avalanche, and the avalanche dragged his rope a hundred meters (328 ft)." Boris later told Belyaev that Vavilov was rolling along the couloir, "like a log", a bloody streak stretched from his broken head in the snow.

Schneider is in shock. He cannot move, sits and does not take his eyes off Vavilov. "The nature of the fall, the position of the body, the absence of any signs of life for one and a half to two hours then led me to conclude that Vavilov was dead. I didn't dare to go down to him on the rocks, for fear of falling," he will later explain.

Already at dusk, Boris forces himself to climb and go out onto the snowy couloir, on which he descends. On the way, he several times saw Vavilov lying in the same position, which finally convinced him: Oleg was dead.

Perhaps Boris intended to lower Vavilov with the help of Sayasov in the morning. But Yuri had a sprained ankle and was helpless. Going to Dombay in total darkness (there was a new moon) when they were totally exhausted was pure madness. Schneider decides to stay in the kosh and wait for his teammates here. They did not sleep all night. They fell asleep at dawn. Around 10 am, Boris still decides to go to Dombay. Yuri waddles along with him.

Shafarevich could not have discouraged anyone from going to Oleg’s help on the evening of February 4, since the deadline for returning of the climbers expired was February 5 at 10:30 am. On that day, the morning was beautiful, sunny. When the comrades did not return on time, everyone thought that the guys had just overslept. Therefore, rescuers (Nemytskiy, who had no experience in rescue work, Shafarevich in crumbling boots and Belyaev, weakened after illness), equipped only with a rope and an ice ax, left Dombay at 11.30 am. They met with Schneider and Sayasov at 1 pm. Learning about the tragedy and seeing the terrible state of Schneider, they began to think what to do. Belyaev called immediately to rise to Vavilov. But Schneider refused to go to Semenov-Bashi: he was tired, did not sleep all night, did not eat for more than a day, and it would take 8-9 hours to get to Vavilov. Nemytskiy decided that Shafarevich and Belyaev would remain in the Alibek camp, where they would wait for Schneider and other rescuers.

In order to warn the local authorities about the tragedy and agree on the transportation of the body, Nemytskiy, together with Bari and Vorobyeva (there is little use of 45-year-old women who had no experience in rescue work) goes skiing from Dombay to Teberda. In Gonachkhir, when he fell, he dislocated his shoulder. I had to quit skiing and continue walking. Due to this injury, Nemytskiy was never able to return to Dombay. And there events developed as follows.

In Dombay a snowstorm with a snowfall began on the evening of February 5. This was the reason why rescuers did not leave on the evening of February 6. Although the weather did not improve by dawn, Schneider, the forester Panchenko and Krasilshchikova nevertheless went to Alibek, where they arrived by 2 pm. At the same time, Schneider was limping with a sprained ankle joint. According to Belyaev, by this time visibility dropped to 10-15 m (30-50 ft), the thickness of the snow cover reached 30-40 cm (1-1.3 ft) with incessant snowfall. Avalanches were grumbling the mountains.

By the morning of February 7, a meter (3.2 ft) had snowed, the snowfall did not stop, which made the rescuers descend to Dombay. On February 8, the group left for Teberda, where they arrive only the next day. Schneider and Belyaev wanted to stay in order to start the search after the snowfall. They had neither money nor products. They went with the rest.

– 4 –

The "climbing society" court of justice

February 14, the day skiers return to the capital, Oleg's unnle, the President of the USSR Academy of Sciences S.I. Vavilov allocated 10 thousand rubles for the search operation. All-Union Committee on Physical Education and Sport formed a search party from experienced and famous climbers: A. Sidorenko, M. Anufrikov, P. Zakharov, V. Tikhonravov, V. Bergyallo, P. Bukov. It included A. Belyaev, B. Schneider and Oleg's widow Lidiya Kurnosova.

Schneider behaved strangely in Dombay. In 2004, in an interview with Y. Rokityanskiy, Kurnosova said: “Schneider was reluctant to search, sometimes he was literally dragged. Sidorenko asked: "Where did you last see Oleg?" He was always silent." If Lidiya Vasilyevna had talked kindly with Boris, perhaps he would have pulled himself together. But then she suspected that Schneider was involved in the death of her husband. As for the "fellow climbers", they behaved like tipsy drunks. According to Kurnosova’s memoirs, "he (Schneider) was scolded, grabbed by the chest, they used profanity against him, sometimes even rushed to beat him, accusing him of Oleg’s death".

On the first of March, when the group reached the rocks, Schneider was able to explain in detail which way they went, where they had a rest, showed the place where Oleg slipped and fell, where he himself stand. The next day there was unrest in the group: climbers were indignant at the poor nutrition, they said that because of 6-meter (20 ft) snow they would not find anything, searches should be carried out when the snow begins to melt.

On March 4, the team leader Sidorenko drew up an act on the work done. According to his description, the scene of the accident was a rock wall with a steepness of 70-65 degrees, a height of 60-70 m (200-230 ft). According to the members of the group, a mid-skilled climber could go down the rocks to Vavilov in 30-40 minutes. Schneider did not sign the act. Experienced climbers explained to me why.

Arguing that one can go down from rocks 20-story high, Sidorenko and Co "forgot to add" that for such a descent Schneider should have: a) a partner; b) a rope; c) climbing boots with hobnails. He had only an ice ax. If Schneider tried to go down in slippery ski boots, he would have ended in an accident.

On March 12, 25 "representatives of the mountaineering community" dismantled this accident at the Volunteers Sport Society "Nauka". All skiers made excuses and repented, except for Schneider, who understood that as an experienced climber, as a senior in the two, he was to blame for the death of Oleg.

Sidorenko's act was not presented to the "climbing society" on April 4, he didn’t tell what the cliffs were, he only stated: "We came to the conclusion that Schneider could certainly go down to Vavilov. He had no desire to do this. He also considered it unnecessary to warn the rescue group as soon as possible... Such behavior is shameful for a climber... such a person does not belong in the ranks of Soviet climbers".

The word of the famous climber was believed. Then the saga began, the subsequent dismantling, everyone vied for denouncing Schneider saying that: he left his comrade in trouble, he has no conscience... The suggestion of the famous climber Letavet that Schneider’s behavior might be explained by shock drowned in the riot of loud accusations.

On April 1, at a meeting of the presidium of the mountaineering section of the VKFS, where 72 people gathered, the commission, which examined the accident, released its findings and offered to punish the group members.

Nemytskiy was removed from the Presidium of the Alpsection, he was forbidden to lead mountaineering and hiking events, to participate in events of All-Union significance and record setting groups. Schneider was disqualified by banning participation in events of sports societies. Belyaev was forbidden to lead any ascents in 1946, Krasilshchikova was reprimanded; the rest were publicly rebuked by the VKFS "for their unworthy behavior of climbers and Soviet people".

– 5 –

The ice ax

In April, VKVF allocates 20 thousand rubles to search for Vavilov. Letters are sent to the secretary of the Kluhor District Party Committee and the district prosecutor asking them to send a surgeon and investigator to Dombay to determine whether Vavilov died immediately or if he was alive for some time and could be helped. A search expedition has not yet left Moscow, when Nikiforov, deputy chairman of the VKFS, addresses the Prosecutor General KP Gorshenin with a request to prosecute Nemytskiy and Schneider. The reason for this haste was explained to me by an veteran climber: “If a relative of a high-ranking person died, sports officials always tried to initiate a criminal case. However, no one was convicted in these cases."

I found the report on the work of the second expedition in the State Archive of the Russian Federation (GARF).

On April 21, Zaharov, Gusak, Sidorenko, Anufrikov, Maleinov, Bergyallo, Kurnosova arrived in Teberda. Since the relatives decided to bury Vavilov in the Caucasus, Zaharov agreed that after the discovery of the body, it would be photographed from all sides and lowered to Dombay, where a medical expert and investigator would arrive. Due to heavy rains, the demolition of the bridge over the Alibek river and the fall of 15 avalanches, they reached the place of the search only on May 1. After a thorough study of the area, the group concludes that "Schneider’s testimony about the path of climbing the wall, the place of Vavilov’s slip, his fall, a stop on the couloir, and Schneider’s finding an easier way to the ridge after Vavilov’s fall is quite possible."

Since Kurnosova was still in doubt, that Schneider was still somehow to blame for Oleg’s accident, climbers went along the Vavilov-Schneider path on May 7 to refute or confirm these doubts. After which Sidorenko writes "Conclusion: The wall along which Schneider and Vavilov climbed is above 60 m (200 ft) with inclination of 70-75 degrees. The total denivelation of Vavilov’s fall from where he slipped to the beginning of the couloir is 50-55 m (164-180 ft). The horizontal distance of Schneider from the place of Vavilov’s fall is 30-35 m (100-115 ft). The "bottom" of the couloir where Vavilov’s body ended after the fall is not visible from any of the sections located nearby the approximate location of Schneider on the ridge. Thus, Kurnosova was convinced that Schneider could not throw her husband into the abyss. But she was tormented by another question: what if Oleg was still alive after the fall?

The search was long. In June, Zaharov and Anufrikov left for Moscow for family reasons, then Gusak and Maleinov left on official business. They were replaced by the head and instructor of the "Nauka" alpine camp Nazarov and Nikitin, as well as the instructor from the "Molniya" alpine camp Orobinskiy. On June 10, when clearing the couloir of snow with controlled avalanches, Kurnosova found her husband’s body.

In the article by Y. Rokityanskiy “The Son of a Genius” Kurnosova is telling the following story. After the discovery of the body, she brought from Teberda two police officers who wrote her a "death certificate", which stated that Oleg "has a mark from the ice ax blow in the temporal region to the right". She brought two copies of the document to Moscow; one handed over to the LPI, from where it disappeared. However, for the article, a death certificate was faxed, which stated that Oleg Vavilov died while climbing Semenov-Bashi. There was no mention of a wound in it. What document did Kurnosova refer to?

From the telegram of the rescuers, it was known that they were taking the expert opinion to Moscow. But I did not find this document in the GARF. I found that in 1946-47 in Dombay, acts were drawn up on the death of climbers. If the death was suspicious, the body was examined by the forensic expert from the city of Kluhori (now Karachayevsk) S.G. Zhgenti and the head physician of a Teberda hospital. After that, a "Burial Act" was drawn up with a description of the injuries. And therefore, it can be assumed that doctors arrived in Dombay with Kurnosova, and she brought to Moscow not only a death certificate, but also a "Burial Act". In search of the latter, I turn to the second husband Kurnosova Fradkin. Moisey Iosifovich is familiar with the document, but cannot find it. I asked him if he can remember whether there was the mention of a blow with an ice ax in it. Fradkin was indignant: “Lidiya Vasiliyevna could not say that. The document spoke of the wound with "the size of an ice ax shovel"!

(Ed. - the ice ax opposite end of the pick is called adze)

Most likely, the expert did not have a measurement ruler handy in Dombay, but nearby there was an ice ax with which climbers went in the search.

Despite the results of my research, Yuri Vavilov is still convinced that Oleg was killed, and that a criminal case existed. I asked him why then Kurnosova was not interested in the course of the investigation? "She was not to be upset."

I can’t believe that Kurnosova, thanks to the persistence of whom two search expeditions took place, which did not give up even when the search party members started to run away, ceased to be interested in the circumstances of her husband’s death. And therefore I can assume that the doctors in Dombay explained to her that Oleg had suffered injuries incompatible with life during the fall, and a lifeless body was rolling along the couloir. Therefore, no criminal case has been instituted.

It seemed that you could put an end to this story. But I was haunted by an essential detail - Schneider’s behavior on that ill-fated day.

Schneider (41), good skier, was a very experienced climber. He had 11 ascents to the eastern and western peaks of Elbrus, the conquest of three peaks (Lyalver, Gestola and Katyn-Tau) of the famous Bezengi, traverse Bzhuduh and Zamok, the first winter ascent to the peak Molodaya Gvardiya, first ascent (traverse) of the three peaks of the Belaya Shapka, etc. He was the leader of the groups in most cases. Since 1937, he participated in rescue operations, including transporting victims from Elbrus, and he was the head of the Misses-Kosh rescue station. Why did such an experienced man on February 4 so flagrantly violate the rules of mountain climbing, and acted so inadequately?

– 6 –

Who are you, comrade Schneider?

I’ve been going over Schneider’s documents for the umpteenth time — official and sports biographies, questionnaires, certificates of employment and studies, statements, etc. He was unusual and outstanding as a person. In 1924 he entered the Physics and Mathematics Department of Moscow State University. After the 2nd year at the request of the Komsomol, he went to the factory, where he worked as a turner, was the secretary of the Komsomol organization. In the 30th year he entered the IPH (Institute of Philosophy and History, created on the basis of the humanitarian faculties of Moscow State University). After 2 courses, he left for family reasons, worked as chairman of the factory committee and taught Marxism-Leninism in courses at the party district committee. In the 1938 he entered the elite MIPLH (Moscow Institute of Philosophy, Literature and History), where the competition was almost 20 people for the place where A. Tvardovskiy, K. Simonov, D. Samoilov, A. Solzhenitsyn studied. In the 1941 the institute merged with Moscow State University. In 1942, according to the shortened program, Schneider graduated from Moscow State University. In the years 1942-1944 he was the political editor in Glavlit, then in 1944-945 the political editor at Mosoblgorlit.

Well, I think everything is clear: during the war, Moscow State University was evacuated to Ashgabat, where Glavlit went too, so he got in. Or maybe he was not taken to the front due to illness? But if he had serious health problems, how then in the 1945 he was able to make the most difficult ascents on the Tien Shan? It is strange.

While going over Schneider’s documents again, I suddenly noticed something. In the questionnaire, which lists ascents by years, and in a sports biography for 1943, are listed the Sella, Abaya, Tuyuk-Su passes and the peaks of Abaya, Tuyuk-Su, Molodaya Gvardiya, Komsomolets, Amangeldy, Molodezhny are indicated ... I opened a map: Sella pass is the Caucasus and Abay, Tuyuk-Su and Young Guard, etc. are in Zailiyskiy Alatau (Kazakhstan).

I can guess how Schneider came to the Caucasus. He did not evacuate from Moscow, as his father remained here, who was in charge of transportation at the People's Commissariat for Textile Industry. He was hardly sitting in the audience. Either he got, like other MIPLH students, into a fighter battalion that destroyed saboteurs in the frontline and then defended Moscow, or, among other athletes, enlisted in the NKVD Separate Motorized Rifle Special Purpose Battalion (OMSBON) and fought behind the front line. The second one is most likely, for he was fluent in German. As I established, Schneider was not Russian, as indicated in the documents, but German. And until the age of 14 he lived in the village of Bulganak, Simferopol district of Crimea - the former German colony of Kronental, founded under Alexander I.

In the summer of 1942, Schneider could get to the Caucasus either with the OMSBON, which was engaged in the fight against German saboteurs and gangs of deserters, or among those 150 climbers whom Pavel Sudoplatov sent to Transcaucasia on the instructions of Beria. The latter prepared the Red Army for military operations in the mountains, evacuated local residents, mined the passes and participated in their defense, were scouts and guides. Schneider, who hiked the Central Caucasus up and down, could be very useful here.

And how did he get to Kazakhstan? I re-read the questionnaire. Here it is! Answering the question: where and when did you work as an instructor, Schneider at the very end writes: "1943. school in Alma-Ata."

I am looking online for a school of instructors in Alma-Ata. Bingo! At that time, when Boris was to sort Glavlit’s pieces of paper, at the famous Gorelnik school (which was subordinate to the VKFS and the People’s Commissariat of Defense of the USSR), he trained mountain shooters, or rather mountain scouts-saboteurs.

The only person who happened to work with school documents stored in the Central State Archive of the Republic of Kazakhstan is Pavel Belan, a doctor of historical sciences from Alma-Ata. But in his article "Mountain shooters from the Gorelnik" there is no instructor Schneider. Lyudmila Varshavskaya from Alma-Ata wrote in 2005 about Gorelnik. She managed to talk with the holder of the Order of the Red Star, three orders of the Great Patriotic War, Yuri Menzhulin. Yuri Nikolaevich is a legend. In 1943 after being wounded, he headed the school, in the spring of the 1944 he went to the front, fought heroically in reconnaissance and even managed with his fighters to take the Russian pass behind the Germans. After the war, Varshavskaya and her friends found the phone number of Menzhulin, but they warn me that he is seriously ill.

Hearing his weak voice, I am in seventh heaven. I explain about my research and ask if he remembers Schneider.

- Of course, I remember, - Menzhulin answers, and his voice grows stronger. - A tall, thin, shaggy, groomed philosopher. He was a calm man, a good teacher, he explained everything to the cadets intelligibly. At work - meticulous, accurate and easy going. He prepared cadets not only theoretically, but went with them to mountain tactical exercises, practiced tactics of military operations. He was good with firearms. I remember he courted a pretty instructor Galya Sivitskaya, and saw more than once how they cooed. But then she married Misha Grudzinskiy, the chief of staff of the school.

– 7 –

- Could Schneider come to Gorelnik from the Caucasus?

- Yes, although he did not talk about it. We accidentally learned that one of our instructors fought in the Caucasus. But he also did not say anything: either he signed a nondisclosure, or there was an order from the command.

- Could Schneider be an agent of the NKVD?

- "Sneaker"? No way! We knew all the "sneakers". If he worked for the NKVD, we would easily figure it out and try to get rid of him.

I tell Menzhulin about the tragedy at Semenov-Bashi and the showdown.

- To judge Schneider, you have to be in his place, - he says. - In the 1943, in front of me and the adjutant, Colonel Gorin flew from the summit and fell to his death. We were in shock for a long time. They could not evacuate the body through two passes. They blamed us, too, they said we were careless, but everything was quickly forgotten because of the war. And the body was taken out only after a month, when a large group was sent for him.

- Could Boris kill Vavilov as a result of a quarrel?

- Impossible! This is completely ruled out because he was a kind and intelligent person.

In a sports biography, Schneider indicated that he spent 4 months at school. Pavel Belan, who nevertheless managed to get in touch with, immediately reported: he met the name of Schneider in the book of orders for school. On August 2, 1943, Schneider was appointed commander and instructor of the 3rd Division. Gratitude was given to him on August 15, September 27, and October 2 for conducting the Alpiniade and climbing to the top Shkolnik with 38 recovering officers and soldiers "in difficult weather conditions", "for honest fulfillment of assigned duties" during the mountain tactical campaign of cadets, and "for excellent teaching work".

After October 2, the name of Schneider does not appear in the documents, there is reason to believe that in early October he left Gorelnik with the first graduates of the school. 60 people (48 graduates, the rest - instructor commanders) were in the camp at the foot of Elbrus. 13 people remained in the camp as instructors, the rest were assigned to the Arctic, Karelia, Svalbard, and Iran. It was rumored that most of the cadets of the first and second graduations fought behind the front line, including in the Carpathians, the mountains of Yugoslavia and the Sudeten Alps. The operations in which they participated are classified today. According to Menzhulin, he hasn't met any of these 102 cadets after the war...

I don't know where was Schneider sent. In Moscow, he appeared in April 1944. It seems to be working as a censor in the Mosgoroblit (another cover?), and part-time he taught at the Moscow Institute of Contemporary Art, from where he quit under the pretext of employment at courses of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks. In November, having passed exams for graduate school, he again disappears and appears in the capital only in May of the 1945, while at the age of 39 he is discharged. Is it because of mental problems? Today they often talk about the Afghan and Chechen syndrome. But about how the Great Patriotic War affected the psyche of people, we know almost nothing.

In the summer of the 1945, Schneider leaves for an expedition to the Tien Shan. Upon returning, he learns that he was expelled from postgraduate studies. It is possible that then he decides to change his life and become a professional instructor in the climber. The tragedy on Semenov-Bashi destroyed all his plans.

In July of the same 1946, he wanted to go to the mountains with a group, for which he took a certificate from the VKFS from a personal file at the Institute of Philosophy, where his participation in the Chatkal expedition was highly appreciated. But because of the ban from the VKFS he was refused. He left for the Caucasus alone and went to the "Shelter of the Eleven", where he wrote a suicide note: "No one is to blame for my death, I’m leaving for the Elbrus pass."

There is no better place to commit suicide. One has only to sit down, unfasten the jacket, and then a frost of 30-50 degrees (-20-58F) will quickly do its job, the wind (up to 50 mps) will carry the body through the icy desert to the nearest crack. But some climbers found the note and went to the pass. Cursing and slapping Schneider on the face, they brought him to his senses and forced him to go down. The famous mountaineer Boris Rukodelnikov, a member of that rescue expedition, told Yuri Vavilov about this story. At a gathering with friends climbers in his house, scientist Rukodelnikov recalled Schneider as a modest and delicate person. He had a chance to talk with him back in the shelter.

I tried to find out what happened with Schneider. It is useless to look for his descendants since he was not married. The house in which he lived in the 1940 was evicted back in the 60s. I tried to set the date of his death by the time of redemption of the party ticket. Here the staff of the Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History helped. It turned out that Boris Ivanovich was getting his party membership cards renewed in 1953 and 1974. But his account card remained outstanding. This meant that Schneider lived to see the liquidation of the CPSU, when the district and party committees ceased to regularly transfer documents to the archives. Only after 1946 did he not go climbing. He could only envy those, "others with peaks still ahead".

Further read › Stalin vs. Science: The Life and Murder of Nikolai Vavilov