Notes of a Geologist

Subpolar Urals. Saranpaul expedition. Book 2.

Preface.

This period of my life and work brought me many joys and sorrows, gave me a huge experience in organizing work in hard-to-reach areas in conditions of complete impassability. It would seem better to sit in a quiet Severouralsk expedition after a major shake-up of the body in Yeniseisk, and gain experience. However, it is not for nothing that experienced people say - the North always attracts those who have been there. The same thing happened to me - I found myself in the North again.

Chapter 1. Karpinsky party. Transfer to Tyumen. Saranpaul expedition. Work area. Leadership.

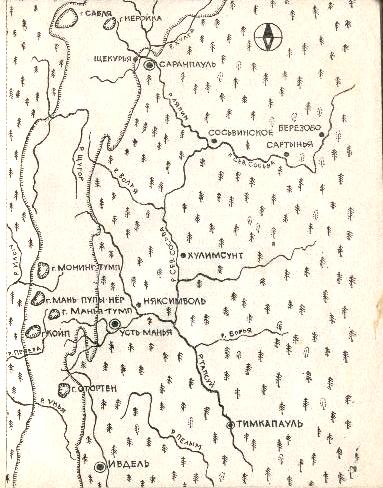

Scheme of the expedition's work area

Arriving from Yeniseisk, I went to ask for a job with V.A. Rivkina, the head of the Severouralsk expedition. The expedition had excellent performance until 1960, i.e. until it was engaged only in exploration of bauxite deposits. In 1960, during another reorganization, two parties were transferred to its subordination - Karpinskaya and Sosvinskaya, which had previously been managed from the city of Ivdel by the Northern Expedition. The results of these parties' work were not impressive, since they worked in remote taiga areas. And in order to somehow improve their work, the expedition had to provide them with significant assistance - both material and personnel. It should be noted, however, that the personnel from Severouralsk did not stay there and a year later they returned to the prosperous bauxite parties.

I have long noticed that people who come to ask for work "from the street", initiative people, are sent to work in the most difficult and unprestigious places. True, this is not only because the person is "from the street", but to a greater extent because people do not leave good places and there is no personnel shortage there. Vacancies remain only in "bad" places.

In this case, this is what they did with me. Vera Abramovna did not leave me in Severouralsk, but said that I needed to go to "strengthen" the Karpinsky party. The party was based in the settlement of Sosnovka, where loggers lived, but after six months it moved to the settlement of Veselovka, 7 km away. from Karpinsk.

For six months I led a drilling team, and in the spring I asked to work as a mining foreman, and I traveled with a detachment of miners around three districts, digging shafts. The work and life of the people in the party and at the sites was organized well. Compared to Yeniseysk - nothing like it. In winter, everyone lived in warm, well-renovated old houses. The stoves were regularly heated by technicians. Water for drilling was delivered by water trucks from a pre-drilled water well. People worked 4 days, then a shift change. They transported by car. I established good relations with the mining inspection, passed an additional exam and received a "Unified Blasting Book" for open and underground work. I got good practice in obtaining permits for the right to carry out blasting operations, as well as police permits for the right to transport explosives. I practiced a lot myself in shafts during the direct production of blasting operations. I myself received explosives at the Vorontsovsky mine. The knowledge I gained from these jobs turned out to be very useful.

In the fall, soon after my arrival, I bought myself an M1M motorcycle and drove from Severouralsk to Sosnovka several times in the winter, overcoming the off-road conditions in the area of the village of Berezovka. Sometimes I had to drive on the same track as the ZIL-157. In the summer, a group of 3-4 people rode several times on a pioneer car with a motorcycle engine along the narrow-gauge railway from Sosnovka to the upper reaches of the Vagran. True, this event was not at all safe. It was necessary to notice an oncoming train in time, everyone jump off and manually remove the pioneer car from the rails, dragging it to a safe distance.

Once, completely by chance, I heard a program on the radio about the head of the Yamalo-Nenets geological exploration expedition, Vadim Bovanenko. The program was well-structured and I listened to it with great interest. His story was told - how he studied in Moscow, how he played basketball (he was about 1.9 meters tall), how he ended up in the North, in Salekhard, and what he did there. It somehow sank into my soul - after all, the Tyumen region is very close.

In addition, Nikolay Ivanovich Polshchikov worked as a tractor driver for us, still relatively young, but a war veteran. He received his first baptism of fire at the age of 18 in the famous tank battle near Prokhorovka in 1943, where he was a mechanic-driver of a T-34 tank. He joined the Karpinsky Party in 1957, having arrived from the Tolyinsky Party, which at that time was located in the Tyumen Region, but subordinated to the Northern Expedition, the Ural Geological Administration.

- 2 -

When in 1957 N. Khrushchev formed territorial governing bodies - economic councils, then geological organizations located on their territory were transferred to their subordination. Thus, the Tyumen economic council ousted geologists of the Ural Geological Administration in Sverdlovsk from the territory of the Subpolar and Polar Urals (geographically this was the Tyumen region). In my opinion, this was a gross mistake. The Ural Mountains and the territory closely adjacent to them are in fact a single geological province and the search for mineral deposits should have been coordinated from a single Ural center, which Sverdlovsk has always been. In 1958, the Ural Geological Administration partially liquidated and partially transferred to the Tyumen Geological Administration its organizations in those areas - the Polar-Ural Expedition in the Polar Urals, the Nyaksimbol Geophysical and several parties in the Subpolar, including Tolyinskaya and Ust-Maninskaya.

However, let's return to Polshchikov N.I. We often talked about hunting and fishing. He always recalled these things when he lived in Tolye. His stories about the amount of game and fish there, their size, caused, at the very least, surprise, and often mistrust. Reality overturned his stories - he saw only a small part of what was really there.

I knew nothing about the geologists of Tyumen - there was no information anywhere. True, two events from radio and newspaper broadcasts have remained in my memory - the discovery of gas in Berezovo in 1953 and the oil obtained in 1960 at one of the wells of the Shaim expedition. I was again drawn to the North after these stories of Polshchikov and the already mentioned radio broadcast. And I decided to go to Tyumen to the geological department.

For two days off, I asked the party chief for 3 more days and left. Communication with Tyumen was not very convenient - it took 4 days to get there and back. I arrived at the geological department. It was located in the city center next to the regional party committee on Vodoprovodnaya Street, 36. It occupied one entrance of an apartment building - 4 floors. From the personnel department, they sent me to the office of the chief geologist.

There the door was open and a short man with a round face - it was the chief geologist of the department, L.I. Rovnin. - asked me who I was and where I was from, what I did and what I could do. There was another relatively young man in the office with him. As it turned out later, it was the senior geologist for solid minerals, A. I. Podsosov. They consulted for a while and said that they agreed to take me and send me to the disposal of the head of the Polar-Ural expedition, S. G. Karachentsev. It was clear from the name that it was located in the Polar Urals, at the station 106th km of the Seida-Labytnangi railway. I agreed. In the personnel department, they quickly wrote me a letter to Rivkina asking her to let me go and transfer me to Tyumen.

In addition to the pure attraction to the North, I wanted to get some independent section of work, because I felt that I had the strength, knowledge and desire for such work - I had already outgrown the position of an ordinary performer. Of course, I still lacked experience, but it could only be obtained on the job. After several years of work in the Severouralsk expedition, I would have been entrusted with greater responsibility, but I intuitively felt that my knowledge could be in demand now, but only in the North.

The party chief, having learned why I was going, immediately said that if he had learned about this matter earlier, he would not have given me such an opportunity. Rivkina V.A. at first persuaded me to stay, but then, having understood my firm intention to leave, she signed the transfer.

The preparations were short-lived and in early November 1961 I left for Tyumen. I came to the personnel department, and there they told me that I should meet with the head of the newly organized Saranpaul expedition, Chepkasov V.A. I had never heard of such a name or expedition before.

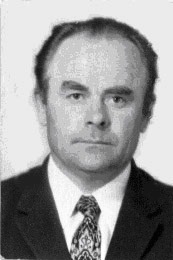

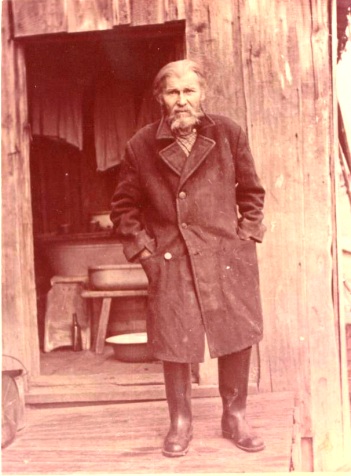

Chepkasov V.A.

We met. He was a relatively young man, somewhere under 35, below average height, but broad-shouldered and stocky, with extremely thick, overhanging eyebrows. They made him look gloomy and taciturn (which was not confirmed later). The manner of his conversation with me was largely evaluative, and the result satisfied him to some extent. He told me that an order had been signed a week ago to organize this new expedition, and he offered me to start working in it as a drilling engineer, though with the prefix acting. Such a prefix gave the manager the right to remove a person from the position at any time without explanation or to fire him. But it also gave the right to frequently transfer a person to other jobs at the discretion of the manager. As it turned out later, all newly hired as heads of geological survey parties, their senior geologists - all young guys, also had the prefix acting. It was a management style, although I still don’t know whose.

- 3 -

A week after my fairly intensive work, the head of the expedition promoted me to senior engineer, but the prefix "acting" remained. My salary was 150 rubles, plus a belt coefficient of 30%, plus field allowance of 3.5 rubles per day. In addition, Saranpaul belonged to the regions equated to the Far North and had the corresponding benefits. When I noticed that at first I was sent to the Polar Urals, Veniamin Aleksandrovich did not react clearly.

Chepkasov V.A. was already an experienced leader. He worked in the North for more than 10 years. He began working at "Dalstroy" in Kolyma, then moved to the Polar Urals, where he held all the positions up to the head of the Polar-Ural expedition.

The second person enrolled in the expedition was the deputy. Chief of General Affairs Ilyashevich Mikhail Vasilyevich. He was quite a colorful figure in many ways. A tall man over 50 years old, with a completely curly head, thick lips and a wide flattened nose. This appearance suggested that he could have African roots in his genealogy. In the early 1950s, he moved from the position of regional prosecutor in Kazakhstan to work as the chief of the Turgai geophysical expedition, after which he was transferred to the position of chief of the Nyaksimbol geophysical expedition as part of the Ural Geological Directorate. Many knew him and told how he always walked around the village with a pistol on his stomach, behind his belt. After the Ural geologists left these places, he came to work for the Tyumen geologists - he was deputy chief of the Sartyninskaya oil exploration expedition, in the Berezovsky district on the Severnaya Sosva River. After Sartinya's lack of prospects became clear, she was demoted to a party, and Ilyashevich was transferred to Saranpaul. In Sverdlovsk, he managed to get an apartment on Gagarin Street, to the left of UPI, towards Pionersky Settlement. Thus, after the chief and his deputy, I was accepted as the third person, i.e., I started work from scratch.

One unusual incident gave impetus to organize a whole new expedition. A geological survey party led by G.G. Efimov dug several pits in the floodplain in the 1961 season in the upper reaches of the Khobeyu River. When washing sand in one of them, N92, they washed out gold by weight, which, when converted to volume, gave a content of about 30 grams per cubic meter of sand. One gold nugget had a decent, oblong size, close to a "cockroach". When the Geological Department learned about this, they ordered the sample to be urgently delivered to Tyumen.

A.I. Podsosov immediately flew to Moscow with it and showed these golden "cockroaches" in many ministerial offices. This made an indelible impression on some. I also noticed later that some, even very high-ranking ministerial officials, took at face value the artist's well-done and colorful pictures, which had nothing in common with reality.

The end of this story looked like this: after the spring flood in 1962, they found this pit and laid 4 new ones on four sides - not one of them showed gold in the samples. Then they gave the order to clear pit N92 and take samples directly at its face - and there was no more gold there. Here is such an unusual story.

Of course, the question of creating a new expedition here had matured even without this incident with gold - the huge region of the Subpolar Urals remained without systematic geological research after 1957.

The expedition was organized with the purpose of expanding the scope of geological surveys on scales of 1:50,000 and 1:200,000, organizing the search and exploration of placer and bedrock gold deposits, building materials, coal, as well as geophysical studies - aeromagnetic and gravity. An aeromagnetic party under the leadership of Latypov A.A. with a base in the village of Nyaksimvol, the already mentioned party of Efimov G.G. and one drilling team for one survey party, for some reason called a drilling party under the leadership of Sidoryak I.M., were already working here. All of them were subordinate to the Salekhard Geological Exploration Expedition. Since November 1961, they have been subordinated to the new leadership of the Saranpaul Complex Geological Exploration Expedition.

The area of work was very large and was located on the territory of the Berezovsky District, Khanty-Mansiysk National Okrug. From south to north - from the borders of the Sverdlovsk Region to the upper reaches of the Khulga River - about 600 km. From the west - from the axial part of the Ural ridge to the east more than 100 km. The entire territory of the expedition's activities in the summer was absolutely impassable for conventional land transport - cars, tractors, tracked tractors. Only 2 special tracked amphibious transporters K-61 along the river bed, which appeared in 1963 - in some places by swimming, and in others on tracks, could reach individual areas of work. In winter, after the swamps, lakes and rivers froze, it was possible to deliver cargo by land transport with high cross-country ability along winter roads. In the mountains, the only transport was pack horses and people. And in general, the entire work area was simply penetrated by countless rivers, streams, lakes, swamps. Forests were located, as a rule, along the rivers.

The main rivers were the Severnaya Sosva and its tributary Lyapin, practically navigable in any summer. Lyapin in the Saranpaul area merged from many rivers - Manya, Khulga, Shchekurya, Polya, Yatriya. Manya was navigable even 60 km higher than Saranpaul. The width of Lyapin is about 400 meters. In addition to the named rivers, there were dozens of smaller ones.

In addition to water transport, aviation was used. From Tyumen to Berezovo there were IL-14s, and from Berezovo to Saranpaul there was an AN-2, and in the summer there was a float version that landed directly on Lyapin. For the AN-2 there were land airfields in Tolye, Nyaksimvol, Ust-Manye and Ivdel. But from Ivdel there were only our special flights, there were no passenger flights.

The first batch of heavy type with the sinking of deep pits in search of placer gold in the valley of the Khobeyu River was supposed to start working in the winter in January 1962 - such was the task set by the Geological Administration. No one cared that at that moment there was no material and technical support. What we were immediately given were tents, axes, picks, shovels, chainsaws and other small things. With this tool it was possible to pass pits up to 3.5 meters deep, and dry ones. But it was necessary to make pits up to 10 meters and with a very decent water inflow. For which powerful pumps were needed, and iron for working with winches - buckets, special hooks, ratchets, winches. For washing the rock mass issued from the pits, valleys and washing trays were needed.

- 4 -

During a discussion with Chepkasov about the problem of drainage during the excavation of pits for placer gold, I told him that the Sosvin party in the Severouralsk expedition uses piston pumps of the "Letestyu" type for this purpose, which are manufactured in the expedition's mechanical workshop, including worm gearboxes RM-250. He showed interest in this matter, but ordered me to go through the entire material base of the department and look for something suitable for these purposes. In the supply department, they offered me hand pumps "Garo" for pumping fuel from a barrel to a tractor tank - they had absolutely no idea what we needed. We needed pumps with an autonomous drive and a capacity of up to 70 cubic meters per hour - this is the usual inflow in gold pits, and it should be on the surface. I also went through all the warehouses and did not find anything close. The thing is that our industry did not produce such pumps.

Then Chepkasov V. told me to get ready for a long journey - first to Severouralsk, on an expedition, to get technical documentation for the pumps there, from there go to Ivdel, to the transfer base. From there, together with Ilyashevich M., fly on a special flight to Saranpaul, get acquainted with the area and return to Tyumen.

Before leaving, I went into a fish store - I wanted to take something with me. At that time, all the stores were literally bursting with fish. Sturgeon cost 2.9 rubles, sterlet 2.6 rubles, muksun 1.6 rubles, cheese 1.1 rubles per 1 kg. All kinds of trash - like pike, crucian carp, chebak - are generally pennies. I saw several hanging golden fish weighing up to 4 kg - these were cold-smoked nelma at 5 rubles per kg. I weighed an 8 kg sturgeon and asked them to put it aside until half an hour before the train departed (otherwise it would have thawed in my hands). The sellers did not undertake to leave it until I arrived. They told me to pick it up right away. I decided to buy a ticket and come again. There was a delay with the ticket because of the queue at the ticket office and I was late for the store.

In the morning I was already in Sverdlovsk. I decided to buy myself a good winter coat. I stopped at the passage - nothing decent. Then I went at random to a second-hand store on Vainer. I saw a magnificent coat, exactly my size - a very expensive dark brown drape and a chic astrakhan collar. Absolutely no signs of wear and expensive - more than 200 rubles. I bought it right away. In the afternoon I went to see my classmates who came to work at NIPIGORMASH. I saw about 6 people. They came out and talked about our graduating class. According to their data, only about 10 people from the entire graduating class remained to work in geological exploration. The rest went to work in various research and design institutes, and the vast majority changed their specialties.

The next day I was already in Severouralsk and showed up at the expedition office. They treated my requests with understanding and promised to prepare sets of drawings of the mechanisms I needed. The next day I went to the Sosvinskaya party, in Pokrovsk-Uralsky. I talked with the head of the party, Krupnov P.A. and senior geologist Ushakov S.A. For me, organizing the excavation of gold pits was a completely new matter, and conversations with them and their advice were extremely valuable to me. They suggested many more details that I had not even suspected. By the way, we continued to contact them on various issues for many years.

The next day, the expedition's technical department printed out all the necessary blueprints for me and I went to Ivdel. There was no direct route there and I had to go first by train to Serov, and from there by another train to Ivdel. Although it is near Severouralsk, I was there for the first time. A small, all-wooden town. I found a pass base, which was located in one of the private houses and was used by Latypov A.A. for the needs of his party. There I met the deputy head of the expedition Ilyashevich M.V., who was already in the house. And looking at my "rich" winter coat, he took me for the chief engineer of the expedition and began to ask me about important topics, although I was a kid half his age compared to him. When I told him that such information was not within my competence, since I was a senior engineer, he calmed down. We spent the night and went to the airfield in the morning. Their plane with aeromagnetic equipment and operators was already there. They loaded up with the accompanying cargo and headed to Saranpaul.

Under the wing there was a fairly diverse landscape. Ribbon pine forests along strongly meandering river beds alternated with marshy undergrowth. Numerous oxbow lakes were clearly visible near large rivers. Residential settlements ended after 20 minutes of flight - this was the north of the Ivdelsky district. Further, no signs of housing were observed for almost 2 hours.

Soon after a two-hour flight, houses of a fairly large village appeared - this was Saranpaul. The plane made a semicircle and landed at the very outskirts, taxied to some house and turned off the engine. The house turned out to be the only one with all its faces - the airport building, the weather station, the chief's residence. We got out and walked to the village - it turned out to be not far from the building of the expedition office. Here is a little background.

Saranpaul is a fairly large village by northern standards and almost everything is stretched along the bank of the navigable Lyapin River. It was conventionally divided into three villages - the first, second and third. Between them there were low-lying areas that were flooded with spring water in high-water springs.

Until recently, Expedition No. 105 of the 6th Main Directorate of the USSR Ministry of Geology was based in Saranpaul, which was engaged in the search, exploration and extraction of piezo-optical raw materials and graphite throughout the country. In general, these expeditions had a very solid material basis everywhere, good labor organization. Yes, apparently, it could not have been otherwise, since these raw materials were of great importance for the country's defense capability. This expedition had 4 mining parties located almost in the axial part of the Ural Mountains, two of them - Neroika and another one on the eastern slope, and Pelingichi and Naroda - on the western. A year ago, the Main Directorate decided to move the expedition base to the Moscow-Vorkuta railway at the Kozhim station - this is the western slope. They assigned it N118. And in Saranpaul they left only part of the warehouses, a small mechanical workshop, transport equipment for supplying their parties on the eastern slope along the winter roads. They put a local cadre - Afanasy Nikanorovich Kanev - in charge of this base. Everything that they did not need, they transferred to our expedition - the office, the Naval warehouse, part of the dormitories. It must be said that at first Kanev helped us as much as he could, especially with spare parts for transport, the manufacture of some iron in his mechanical workshop. He probably expected that someday we would get back on our feet and help him somewhere, but he didn't wait. He soon got tired of our beggary and he came to meet us less often.

- 5 -

The office was located right on the bank of the Lyapin and had a quite decent appearance, both outside and inside. About ten rooms, hot water heating from its own boiler. Stokers worked so as not to freeze the system. Engineering and technical workers were also temporarily housed here. Ilyashevich M., Efimov G.G. were already here, and Latypov and I came up. There were sleeping bags in the rooms. We went to the store and bought something to eat. Everyone sat down at the table, and Ilyashevich M.V. took some dried fish out of the bag. Its size was decent - up to 30 cm in length. I was told that it was called syrok, it was caught in the Lyapin, and all the residents stocked it up for the winter and you could buy a fish for 15-20 kopeek depending on the size. It turned out to be very tasty, especially the large specimens. When you peel it, it glows from the fat that has soaked it.

We drank to our acquaintance, to the good start of the expedition. Efimov, like me, drank very little. After some time, Latypov, for no apparent reason, started a conversation about cockroaches that he allegedly caught in the borscht of a restaurant in Ivdel. Efimov's face suddenly tensed up, his gaze took on an absent expression, and he apologized and said that he had to go out. And he went out. After that, Latypov laughed and said that Grigory Grigoryevich had gone out to puke. It turned out that after all the hardships he had endured in life, Efimov had developed a strong aversion to such stories and events. Fate had treated him very harshly. He is an officer, fought in the active army, but either at the end of the war or immediately after, he was arrested on a denunciation and sentenced under Article 58 to 10 years in the camps. He served almost his entire term in the North - Vorkuta, Salekhard. His fate strongly resembles the fate of Solzhenitsyn A.I., and even outwardly they are very similar. At this meeting, he told only one episode from his camp life - they were given the task of stacking bricks. They did it very quickly, but skillfully left empty spaces inside the stacks, and the volume of the masonry was calculated based on the external measurement. In this case, they earned an extra ration. Of course, he was an interesting, extraordinary person, but fate brought me together with him very rarely in the future, only for the time of random short meetings.

A little later, that same evening, a conversation arose about the air explosion of a powerful thermonuclear charge conducted a month ago over Novaya Zemlya. It turns out that this was a major event in the North. All residents of Salekhard were taken out of their homes, some windows were blown out by the shock wave. In the village of Amderma, windows and doors were blown out. All geologists were taken out of the field from the areas threatened by the shock wave. I think that the shock wave was already dying down, and on October 30 it reached Severouralsk in the form of a strong wind. On that day, a wind blew from the north for several hours with an unprecedented force for these places. It seemed that you could lie on it and it would not let a person fall to the ground. I knew about the air blast, because it was announced on the radio, but it did not even occur to me that its echoes could reach Severouralsk. Later, these events were described by other geologists-surveyors who came to work with us from the Polar Urals. They said that a flash was visible in the distance, but not bright, and a loud hum came.

Ilyashevich M., in addition to solving the expedition's problems, was also busy "knocking out" an order from the department to buy a Volga car for himself. At that time, they still cost 4,000 rubles, but at any moment the price could start to rise, since demand had increased sharply. He received it and drove it to Sverdlovsk somewhere in May of the following year.

A year later, the price for them actually increased.

I met the head of the drilling party, I.M. Sidoryak. Of course, it was not a party at all - one drilling team, and not a full complement. It was engaged in drilling mapping wells at the points of a geological survey at a scale of 1:200,000. He himself had been working in the North for a long time, almost since the post-war times. He was engaged in drilling structural wells under Professor Chochia.

We inspected the houses and dormitory in the village that were given to our expedition. Ilyashevich and I went to the village council to meet the chairman. The chairman of the village council was Ilya Nikolaevich Malyugin, an invalid, he lost his leg somewhere, a man of small stature, but he jumped around the village quite quickly. His salary was 50 rubles, plus northern allowances. The favorite topic of conversation with him during "tea parties" was the question: "Ilya Nikolaevich! Have you seen a steam locomotive?" - And he always answered sharply: "No. Never. I have never left Saranpaul!" The first and last time he had to go to Khanty-Mansiysk was in 1964 for the funeral of his brother, who died among all the passengers of the scheduled AN-24 plane that burned on the runway during landing. His own fate was also tragic - in the late 60s, he froze to death right in the village.

Having finished all my business in Saranpaul, I went to Tyumen. I returned through the village of Berezovo. It was rare to reach Tyumen in one day, because the scheduled An-2 plane arrived in Berezovo after lunch on the return flight and it was already impossible to buy a plane ticket to Tyumen.

I flew there for the first time and went to look for a hotel for the night - I did not know anyone there. I found a hotel in the center of the village. It was a small two-story wooden building, next to the pier. Inside there was a restaurant "Sosva". A place for me was in a room on the second floor, where there were 7-8 beds. By evening, among the hotel guests and restaurant visitors, I saw many aviators - apparently they did not have their own visiting hotel and they used the communal one. The next morning, I flew on an Il-14 to Tyumen, where I arrived after 3 hours of flight.

- 6 -

Chapter 2. Work in Tyumen. Manufacturing pumps. Management. Applications. Recruitment of workers. Flight to Saranpaul.

Upon arrival at the department, I reported to Chepkasov on the results of the trip. He immediately puzzled me with a multitude of matters - it was necessary to place orders somewhere for the manufacture of "Letestyu" pumps, the drawings of which I brought from Severouralsk, and other ironwork for sinking shafts, draw up annual applications for the logistics of the expedition in 1962, and, as people approached the personnel department of the department, select the necessary workers for the expedition. I think that before this he introduced me to the management of the department as one of his authorized representatives on the above-mentioned issues, and I was accepted everywhere without hindrance, right up to the head of the department, Ervie Y.G. Chepkasov himself, V.A. was also overloaded with organizational issues, recruiting engineering and technical personnel, and frequent trips to the district.

The question of where I would live in Tyumen during this period arose - a hotel was expensive and inconvenient. Then he arranged for me to be accommodated in a dormitory for engineering and technical personnel on Kholodilnaya Street - at that time it was already a remote outskirts of Tyumen on the Siberian Highway. The main place there was occupied by a complex of buildings of the vocational school for training drilling personnel and a training drilling rig. There was also a one-story dormitory for engineering and technical personnel. Moreover, between this complex of buildings and structures and the first residential buildings of the city there was a large vacant lot. In the same area, but closer to the city, on Kyiv and Minskaya Streets there were many two-story residential buildings where employees of the geological department lived. I got to work by bus, or if there was no bus for a long time, then I walked for about 25 minutes.

In one of the departments of the department, they gave me a desk and the work went on.

The biggest issue was pumps. I went to the chief mechanic Savin K.I., he looked at the drawings and said that I had to go to the chief engineer of the department. They came. Morozov Nikolay Mihaylovich, in a dazzling white shirt and tie, without a jacket. After my short story about the conditions for driving pits for gold in thawed rocks, he immediately understood the essence of the matter and he did not have the slightest doubt about the need for this equipment. He firmly gave Savin the task of finding the capacity to manufacture them. In my experience, the mechanical workshops of expeditions are always and everywhere overloaded with orders. The issue of making worm gearboxes arose - they could not be made in the mechanical workshops at all due to their increased complexity. By the way, the mechanical workshop of the Severouralsk expedition is much smaller than Tyumen, they were very good at making them. They decided to contact the Tyumen construction machinery plant for their manufacture, but both interlocutors told me that an appeal to this plant was at the level of the head of the department. And in general, they told me to prepare a letter signed by the head of the department with a request to make 2 reducers first, and then - four pumps in full. They decided to make two pumps in the mechanical workshops of the Tyumen expedition at its base in Parfyonovo. I quickly prepared the letter, collected 2 visas from my recent interlocutors and went upstairs to the reception room of the head of the geological department. A small room where the secretary, a middle-aged woman, was sitting, a teletype was clicking nearby by the window. She asked me about my business - she saw me almost for the first time (not counting the visit to Morozov N.M.), and allowed me to enter.

In a medium-sized office (significantly smaller than the offices of some expedition leaders, and not only those subordinate to him), sat a man in a bluish suit, close to 50 years old, with strong gray hair, but with absolutely black thick eyebrows, in thin gold glasses. Under the suit, an absolutely white shirt was also visible. He read the letter, asked me a few small, clarifying questions - it was felt that he was aware of our affairs. He signed the letter without any amendments and told me to take it to the plant myself along with the drawings. This was the famous Yuri Georgievich Ervie in the future - the head of the Tyumen territorial geological administration, in the future First Deputy Minister of Geology of the USSR. Of course, it is necessary to write about him, and not to me, but to people who knew him well, separately, since leaders of the geological service of such thinking and scale of affairs were extremely rare even in those days.

I usually went to the Zarya restaurant at the hotel of the same name for lunch. You could have a very decent lunch there and it was inexpensive. I always had some kind of cold smoked fish appetizer - tesha or sturgeon balyk, Georgian solyanka, a bottle of beer. Sometimes I had fried muksun for a second course. Sometimes a mixed fish solyanka. The quality and variety of good fish in those years was simply amazing - since then I have not seen such variety and abundance anywhere. There was also meat in different forms, and even venison, which was exotic for me.

There were many young geologists living in the hostel, still unmarried. There were some from Sverdlovsk, Saratov and other places. We met many of them in the following years, when we went to our places of work. There, in the dormitory, I first heard tape recordings of V. Vysotsky, brought from Moscow, but they did not make a special impression on me at the time.

However, I liked the tape recorders that the guys used for recording and playback. Soon I went to the store and bought myself a desktop reel-to-reel tape recorder "Dnepr-11" - it was an improved modification of the 10th "Dnepr", which was in the dormitory. It had two speeds - 9 and 4.5. The standard reel was 350 meters, but it also fit 500 meters. At that time, it was a very decent device with 4 speakers and good tone control. It was also not cheap - 145 rubles. I copied a whole reel of rock and rolls performed by Bill Haley's orchestra and some other musicians from the guys. On my next trip to Severouralsk, I took it home. It weighed about 30 kg, and how I dragged it to the station in Tyumen, and how I got it home from the train - only God knows.

One day, remembering Yeniseysk, I decided to try raw sterlet. For some reason, there were no large fish in the store. I had to take small, frozen ones. I thawed it, cut it, salted it. The taste was completely different. Of course, it reminded me of Yenisey sterlet, but I didn't want to eat it raw. I had to boil it.

- 7 -

I brought a small-caliber rifle with me. But my dream remained a 12-gauge double-barreled gun, especially a hammer-action MTs-9. Soon I would be returning to Saranpaul and I needed to buy a gun. I went to the shops. There was no choice at all. Only one of them sold a hammerless 12-gauge IZH-54. I had to take it. I also bought gunpowder, shot, cartridges, a cartridge belt, etc.

But the work continued. For the mining operations, it was necessary to make a number of small ironwork items - buckets, winches, valleys, various hooks, etc. I drew all this in sketches with dimensions, wrote applications with the required quantities, having previously agreed with Chepkasov V.A. the number of mining brigades. With these papers, I went to Morozov N.M. He looked at my sketches and then said to me: "They are very poorly drawn! You are an engineer! You can't belittle your profession like that! If you even make sketches, they should look appropriate too!" He taught me a lesson for life. He took it back. That same day I redid everything and he signed all the documents without any comments. Previously working as a senior drilling foreman, I was used to giving orders to the mechanical workshop on scraps of notebook paper, sometimes in a hurry, not paying attention to the quality of the design, and no one demanded the quality of such papers from me. Here I moved to a completely different level of communication, and I had to learn on the fly and rebuild my psychology

N.M. Morozov himself, according to reviews from people who often encountered him, was a talented engineer and did a lot of useful things in his position as the main one. I felt his special, engineering "nose" when I reported to him about the pumps. He was completely unfamiliar with the technologies of pit drilling and water drainage, but he immediately grasped the main point of the required pumps - high productivity and the ability to pump heavily polluted water. About two years later, he was transferred to the position of head of the Surgut oil exploration expedition.

It took a lot of time to draw up annual applications, since some positions had to be substantiated with calculations. The work was also somewhat new to me. I had to learn - I took annual applications from other expeditions and looked at them there. I often had to go to the deputy head of the department for general issues, Bystritsky A.G. He was already an elderly man with gray hair, short, very active. He conducted conversations with visitors very actively, since most of them always wanted to get a lot from him. He was not one to mince words, he knew the situation well and what he had in the warehouses, and if the opportunity arose he could throw in a "red" word, but he did not abuse it.

This was the same head of the Berezovskaya oil exploration, at whose well in 1953 the unexpected, first in Western Siberia gas fountain hit. He was a real discoverer. I often came to him with requests for obtaining certain materials for the expedition based on radiograms from Chepkasov V., who was in Saranpaul. I often had to go to the warehouses of the administration and look for the things we needed myself.

The entire management treated us well at that time, they understood the difficulties of our formation and tried to help with material resources as much as they could. Of course, they never forgot their main task for a minute - the search for oil and gas. Everything went there first of all - transport equipment, residential buildings, consumables. We got just crumbs for our volume of work. Apparently, this was the right strategy - concentrating all resources on the main direction, and not scattering them on solving secondary and tertiary tasks, which could include work on solid minerals.

The question of hiring workers for the expedition soon arose. Workers often approached the HR department of the department - they called me from there, asking to talk to the next visitor. It was necessary to recruit pit miners, sample washers, turners, carpenters. Those whom I agreed to take were registered at the department, given a small cash advance for the trip and sent to Saranpaul on cargo planes or by scheduled flights.

In general, the category of pit miners on thawed placers is extremely rare - I managed to find only one person. In the Tyumen region, such work was not carried out. They were carried out only in the Urals and the Far East. Miners who worked in hard or frozen rocks using drilling and blasting operations were suitable. Some of them mastered the excavation of shafts in taliks, but most of them failed and retrained for other jobs.

Sample washers were more common, because in the summer season almost all geological survey parties conducted selective concentrate sampling in the beds of rivers and streams. The least skilled went to work as gate operators and other auxiliary jobs. Many of them were beachcombers who went for the season in order to return to the warmth again by winter. However, there were also people who went to earn serious money.

From the first group of people I hired, one stood out - Popik V. He was a local native. Young, tall, a very skilled man. He hired himself out as a miner together with his wife - she was a gate operator. Although he had never done such shafts before, he mastered this business quite well. In addition, he was a good carpenter. He had been through many places and professions. I remember his story about how he served as a warden in the Tobolsk prison. That was the first time I learned and was surprised that some prisoners swallowed their aluminum spoons to get to the infirmary.

My paperwork was slowly coming to an end. Now the most important task was to speed up the production of relatively small pieces of iron for mining operations. I started going to the Tyumen expedition's mechanical workshop almost every day and rushing them to make buckets, cranks, etc. They promised to finish all the small stuff in the first week of January 1962. At the same time, they were making blanks for two "Letestyu" pumps - but they promised to make them only by the end of the first quarter. For the first ten days of January, I ordered a special flight of the AN-2 plane to Saranpaul, estimated the weight of the iron products, and decided to make the rest of the additional cargo with newly hired workers. All the hardware, as promised, was made on time, and having boarded the plane with the workers somewhere in the first ten days of January, 7 hours later we arrived in Saranpaul.

- 8 -

Chapter 3. Saranpaul Again. Landing of the Khobein Party. Kamenev V.M. Kalinin A.S. Katina. Barracks, office, bathhouse. Meeting of the ATL. Wolverine. Return to the expedition.

For the time being, I settled into the engineering and technical workers' dormitory. There were three of us in a room - it was an ordinary wooden barracks.

Immediately upon arrival, V.A. Chepkasov told me that the Khobein party had been reorganized to search for and prospect for gold. Its leader had also been appointed, who would fly to Saranpaul after handing over his affairs in the Tyumen expedition. The senior geologist of the party would also arrive here in a few days. He appointed me acting technical leader of the party. In the near future, I had to initially staff the team from the available people, dress them, give them shoes, select tools, necessary consumables, and at the end of the second ten-day period of January, carry out a helicopter drop-off to the site and begin tunneling work. He also designated the starting points for the work. The first line of pits was to be laid at the landing site along the entire width of the river valley, the second - 5 km away. upstream and there it was necessary to cut down a place for a helicopter landing pad. The third line was laid even higher at 5 km - exactly in the area of pit No. 92, which yielded industrial gold. The deadlines were very tight, and besides, it was impossible to miss any detail, since this was an absolutely deserted area and a complete lack of roads to the work site.

We must pay tribute to the expedition leaders - Chepkasov and Ilyashevich, who closely supervised the preparation for the drop-off every day. In order to land about 30 people with the necessary tools, food, etc., 5 flights of the MI-4 helicopter were required. I provided for the order and sequence of loading and dispatch so that the first to arrive had everything necessary for life, with the last flights the mining tool was sent. The distance was about 60 km. During the preparation, I bought myself an excellent fur suit at a warehouse for cash for 84 rubles. It included a short fur jacket and fur pants almost to the chest with straps. Together with my dog fur boots, it turned out to be a great warm ensemble. (By the way, I still wear this jacket sometimes).

On January 16, I flew out on my own with the first helicopter, having previously viewed the future landing site on the tablet. There were no platforms or open spaces on the bank of the Khobei River, so we landed right in the river valley. The helicopter hovered, clouds of snow dust rose, the flight mechanic opened the door and I jumped out right up to my waist in the snow. I wandered a little to the side and waved my hands so that the loads would be thrown out and the people would jump out. All unloading was done with the helicopter hovering in the air - it only slightly touched the snow with its wheels so that the commander could see the edge of the snow cover and not go lower, which threatened an accident with the machine overturning - when the helicopter lands on a soft surface, it tilts and catches the ground with its rotor blades.

When all the cargo was thrown out and the people jumped out, the helicopter immediately rose up and, having made a slight forward tilt, went along the river valley, slowly gaining altitude. We began to trample a path to the shore in very deep snow. We landed in the very foothills, where there is always a lot of snow. From our place to the relatively flat part was about 40 km. Even before finishing transferring the cargo to the shore, we heard the hum of the helicopter. The people quickly left the previous landing site and the machine again hovered over the river. Everything repeated itself again with unloading, and the helicopter immediately went back. They began to quickly transfer the cargo to the shore and store it in one place. In January, at those latitudes, the day is very short and it was necessary to have time to equip the overnight stay in daylight.

We quickly cleared the area of snow and began to set up a 10-person tent with a flannel lining - insulation inside. In the center, we installed an iron stove made from a 200-liter barrel, and along two walls we built common bunks from fresh poles. While we were setting up the tent, daylight quickly ended, and there was still no helicopter. I thought that for some reason the flight was postponed until tomorrow. We continued to settle in - we laid pine branches on the bunks in the tent, sawed and chopped firewood. It quickly got dark, we lit the stove, lit a candle. We also lit a fire outside and the cook cooked food for everyone at once - this was called pot feeding. The food consumption was written off equally for everyone, depending on the days each eater visited the kitchen.

The frosts were not severe - about 30 degrees - after all, this territory was closer to the Gulf Stream than Yeniseisk. Frosts of about 45 degrees happened here too, but not for more than a week. There were 13 of us in a 10-person tent. We had brought a second one with us, but the stove for it was left in Saranpaul. It was cramped, but everyone settled on the bunks. They assigned a night duty officer to constantly heat the stove. Since we were practically settling among the firewood, our duty officer did not spare the latter at all. At first, I fell asleep from the great fatigue of the day, but soon woke up from the unbearable heat, got out of my sleeping bag, asked the duty officer to turn down the heat a little, but still could not fall asleep. The rest of the people slept and snored quite well. I generally didn't tolerate heat well since childhood and only when I got to the steppes of Kazakhstan, I somehow got used to it and sometimes even began to like the hot dry air. I can't stand humid heat at all. In the morning we got up, had breakfast and went to clear a place for building a barracks for housing. We decided to build it without any tricks, from available raw materials, from the forest that stood around us.

- 9 -

We had brought a chainsaw and a barrel of gasoline for it, so the lumberjacks were provided with work. However, the second day was ending, and there was still no helicopter. Radio operator Sergei Borovskikh flew in with us with an RPMS radio, a very young guy who had just finished courses in Tyumen. In the morning, I gave him a man to help install the radio antennas. I allocated him a place in the corner of the tent and told him to urgently establish contact with the expedition. His work was moving briskly and by lunchtime all the antennas were installed, everything he asked for was done for him - there was only one thing missing - communication with the expedition. The first day he told me that there was no radio reception today. I could not help him with this at all. And the second day was ending - no helicopter, no communication.

I began to think with fear about what to do with sleep on the second night. I imagined this heat again! Then I ordered the men to set up a second tent not far from the first one, without making bunks in it. I decided to try sleeping in a cold tent, without a stove. I chopped up some spruce branches and spread them on the frozen ground. I made a double sleeping bag - I stuffed a small tourist one into a large, regular one and lay down in warm Chinese underwear. I fastened all the fasteners and breathed inside this structure. I fell asleep and slept all night.

In the morning I woke up and couldn't move my arms or legs - all my joints had lost their former mobility. I started moving them very slowly. After about 15 minutes they acquired the ability to bend and straighten. I quickly got out of the bag and got dressed. The impression on my body from this night was not very pleasant, but I slept well and rested. Another worker slept in the tent with me, who also couldn't stand the heat. And on the third night he decided to sleep in a cold tent. I, after some thought, decided not to repeat this experiment, considering it dangerous not only for a living organism, but for life in general. Of course, northern peoples sleep this way, even in the snow, but they wear a malitsa, and on top of that a kukul made of reindeer skins, which retain the heat of the human body much better and do not allow such hypothermia of the body as sleeping in a wadded sleeping bag. The guy who came to spend the night in a cold tent the next night also later refused such experiments.

And there was still no helicopter. My daily conversations with the radio operator did not lead to anything positive - there was no connection. He constantly told me about some magnetic storms, pointed to the tuning levers of the radio, said that he was doing everything right, but there was no sense in these conversations. We did not know anything. And this ignorance lasted for about 10 days - no communication, no helicopter.

The situation that developed at that time, as far as I remember, did not worry me much, because we had a place to sleep and food. But now, in retrospect, you understand that a grave mistake was made on the part of the expedition leadership. You never know what could have happened to us during this time - there might have been no food, stove or tents, someone could have been injured. After all, we were counting on 5 helicopter flights and stable communication with the base. But it was mid-January and the frosts could have intensified even more. Ilyashevich M.V., deputy head of the expedition, remained in Saranpaul and in those conditions he not only could, but also should have sent us at least a reindeer team with a musher until stable radio communication with us or a helicopter appeared. Chepkasov V.A. on the day of our drop-off, he flew out on a business trip to Tyumen.

Once we almost lost an insulated tent. In the evening, at dusk, another person and I decided to take a closer look at some detail on the insulation. We took a burning candle in our hands and brought it closer to the wall. At some point, I noticed that a dark spot appeared on the flannel insulation and it began to quickly expand to the sides. We simultaneously realized that the insulation had caught fire from the flame of the candle brought close and began to quickly slam it with nearby rags. Luckily for us, we began to extinguish it in time, but a hole about a square meter had managed to burn out, and mainly under the bunks, where the flame had managed to slip - we managed to quickly slam the one above the bunks. Then I understood the reasons for the fires in tents, which destroyed them in a few minutes - the chances of extinguishing such a fire are always small. Losing the tent with our things could have turned into a real disaster for us.

After 10 days of radio silence, a joyful radio operator suddenly runs to me in the forest and shouts that there is a connection with Saranpaul. I go to the radio, and indeed - there is a radiogram for me, where they say that the helicopter broke down after the second flight to us and flew away for repairs, that in 4 days they expect another plane to arrive. They ask: why did not contact? Is everything okay, are there any products. The products were really running out and I, remembering the breakdowns, asked to send them on the first flight. Why our radio suddenly started working - I still do not know, but I think that the inexperienced radio operator made some technical errors at first. After 10 days, apparently accidentally pressed some necessary toggle switch and went to the correct operating mode and did not make any more failures. He worked with us until the summer, gained some experience and went somewhere further north, to oil exploration.

Exactly 2 weeks after the first landing, 5 more MI-4 flights arrived in 2 days. All the hardware and personnel (except for the management) were transferred. There were about 30 people in total. We set up 2 more tents and began preparatory work for drilling pits and expanding the work.

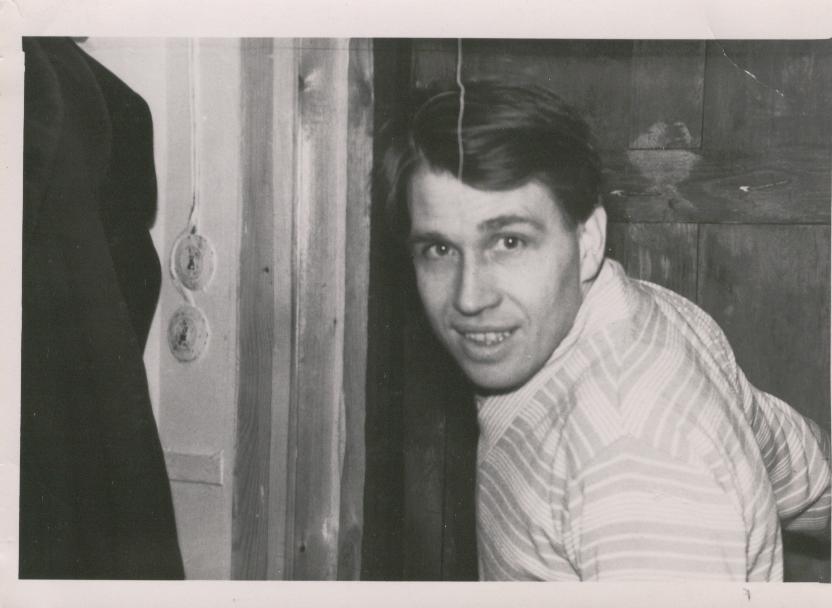

Geologist Misha Katin, a graduate of MGRI, who had come to Tyumen from Eastern Siberia, arrived with his wife. His wife Nelya, a hydrogeologist technician by education, was a tiny girl and was pregnant.

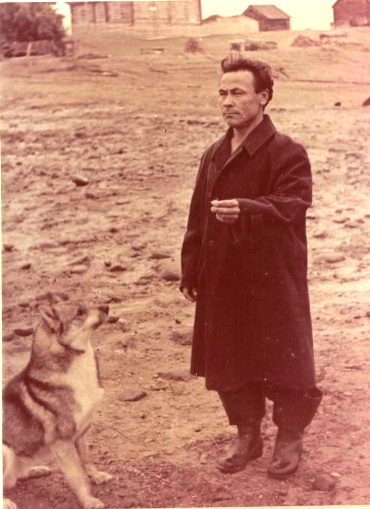

Misha Katin

One of the next days, Katin, topographer Dudkin and I went out on skis to the area of the second line to determine the pits and the helipad on the ground.

- 10 -

While still in Saranpaul, I bought myself new hunting skis for 30 rubles, lined with elk kamus - this is a very strong skin from the lower part of the legs of elks or deer. They were a little short for me, because the owner, a short Mansi, made them for himself. They were made very well - the kamus skins were glued to the skis with fish glue and the seams were almost invisible. On such skis, I walked ahead, paving the way for my partners, who were using ordinary golitsy skis. I discovered the convenience of these skis when climbing a hill - they did not slide down at all and you could climb them head-on without fear. And they slid down with a little braking compared to ordinary skis.

We walked along the valley of the Khobeyu River, along the left bank. There were already foothills here and the first and second terraces were clearly visible. However, we did not see any game during the entire journey, except for tracks of squirrels and martens. The latter were very rare. Apparently, this was due to the fact that there was very little cedar in these parts, and hence few squirrels, and accordingly the entire food chain was broken. There were many unfrozen places on the river, probably underground springs, and the river flow was quite fast. But the surrounding air was so clean and transparent that you just wanted to "drink" it. The forests around consisted mainly of spruce and fir. Pines were rare.

Road in the Hobeyu Valley

We arrived at the place. Dudkin decided and roughly indicated the location of the pit line. Not far away there was a kind of expanding pocket on the terrace, suitable in size for the construction of a helipad, on which it was later built. All three pit lines were perpendicular to the Sobaka-Lai ridge, which was located along the left bank of the Khobei River, and, according to the geologists, should have poured gold into our pits. Later, these calculations were not confirmed. We went back to our camp. After another 2-3 days, the head and senior geologist of the party arrived.

Kamenev Vilen Mihaylovich, head of the party. Before that, he worked in the Tyumen expedition on the exploration of building materials. Originally from Vinnitsa. Jewish, and raised by his mother alone. He graduated from the Dnepropetrovsk Mining Institute and knew Professor Epstein well, one of the few luminaries in drilling in those years. His real last name was Reznik, for some reason he was embarrassed by it and took his wife's last name - Kamenev - when he got married. His wife, Serafima Nikitichna, worked in the Central Laboratory in Tyumen. They already had two sons. In the summer, she moved to Saranpaul and also worked in the expedition laboratory. He himself was slightly taller than average, a little over 30 years old, with a head that was already starting to go bald. It must be said that despite the fact that he had not previously been involved in placer gold, he was actively involved in both the production process and the study of the geological features of searching for gold placers.

Kalinin Aleksey Semyonovich, senior geologist of the party. The man was already quite old - 65 years old, had long been retired, and had lived in Sochi for many years in his own house. In the early 1930s, he graduated from the Industrial Academy. He studied with Stalin's wife Nadezhda Alliluyeva, Nikita Khrushchev and the future USSR Minister of Geology and then Deputy Minister of Medium Machine Building, P. Antropov. He spent his entire life prospecting and exploring for gold, but only in the even greater North - in Yakutia and Magadan. According to his stories, in the early 1930s, geological parties would go on searches for 2 years at a time in places very far from the base. There was no communication. It often happened that fewer people returned than had left at the beginning - they died on the way from illnesses and accidents. There were no estimates for the work. The party chief would receive money at local post offices along his route and he would receive and spend it at his own discretion. I don't know how he came to us, but I think his friends in the Ministry told him about a new organization for gold prospecting, and he, in his words, always wanted to get to the North again. He even came to us with his old dog sleeping bag - it was a very light and warm product. Such quality bags were no longer produced in 30 years, apparently, it was considered expensive.

We soon realized that life in a tent in winter is not easy, and decided to build a large barracks from the damp wood around. We laid a large one, with solid bunks along both long walls and compartments for married couples.

We began preparations for sinking pits. Geologists agreed on their locations on both banks of the river and a couple of pits were laid in the riverbed itself at a shallow depth. On land, pits were dug in the permafrost first for "burning". The snow was cleared and dry logs were laid along the pit contour, the damp logs were placed on top of them and the lower ones were set on fire. In the morning, a miner would come, remove the unburned remains, loosen the thawed soil with a pick, and throw it out with a shovel. During the cycle, 20 cm would thaw, and it was necessary to lay firewood again. One miner had several pits at work at once. The permafrost layer reached 2 meters or more. After the pit reached a depth of more than 2 meters, a manual winch of the well type was installed over the pit. The miner would put the rock at the face into a bucket, which the winchmen would lift to the surface, pour out in a certain sequence and return the bucket back down.

- 11 -

In river beds, the excavation was carried out using a different technology - "freezing". The method is applicable only in winter in severe frosts. The ice on the river bed along the perimeter of the pit is cleared and its entire depth is excavated, with the exception of 6-7 cm, and left for further freezing. After a day or two (depending on the strength of the frost), the miner again removes the newly frozen layer. The thickness of the pillar is determined by drilling a control hole in the ice, which is then plugged with a wooden dowel. Usually, little was frozen in a day or two, and besides, winter was already coming to an end and there was no chance to finish the pit for freezing. In principle, this method is used. To enhance the freezing effect, axial fans can be used to supply cold outside air to the face and enhance the freezing effect.

But still, the miner's work was not only physically difficult, but also required very specific knowledge and experience. The miners who came to us from the 105th expedition or from other mines, as a rule, rarely mastered the craft we needed. Even out of 10 people, not one remained. We can say that out of 20, one mastered the craft, but this one was already becoming a professional.

Everyone imagined that as the pits deepened and their faces reached the level of the river surface, the problem of drainage would arise. Kalinin and I often discussed this problem. He had a historically formed view on this matter from his practice - no iron pumps! These are all chimeras! One good carpenter is needed and the job will be done. He did not believe in the success of using the "Letestyu" pumps. Having learned that Popik was a good carpenter, he agreed with him to make a wooden pump. He made him a cylinder according to his sketches. But Kalinin refused to pay him. Then Popik took an axe and chopped the pump into pieces. From this story it is clear that Kalinin had no idea at all about the future working conditions, that in thawed soils the water inflow into the pit could reach more than 100 cubic meters per hour. He had previously worked only in permafrost, where water appeared in places, very rarely and in very small quantities. That's where his wooden pump could cope.

Three weeks later, they began to cover the barracks for housing with planks. For the first time here I saw how swing saws are used for manual longitudinal sawing of logs into boards and planks. When organizing geological exploration parties conducting drilling and mining operations, the first mechanisms that appear at the base are a mobile power station and a sawmill. Without these mechanisms it is impossible to build housing and production and utility rooms - machine shops, garages, etc. It is possible to build from round timber, but floorboards, ceilings, roofs, doors, window frames can only be obtained from a sawmill. In our case, when organizing the Khobein party, the matter was complicated by the fact that we could only obtain part of the necessary equipment in July 1962 with the opening of summer navigation to Saranpaul by water transport. Therefore, when starting to build a barrack for housing, we had to use old grandfather's methods of obtaining boards and planks - manual longitudinal sawing of logs with swing saws. For this, a platform was built at a height of about 2 meters, a log edged on both sides was fixed there, one person stood on this platform and pulled the saw up, and the second stood below and pulled the saw down. The saw itself was twice as heavy as a crosscut saw, the teeth were also longer and sharpened specifically for longitudinal sawing. It was the hardest physical labor, something like 'Egyptian'. I myself am not a flimsy build, but I could not work for more than 10 minutes. They covered the ceiling and covered it with frozen moss. Inside, on both long sides, they made common bunks, covered them all with felt. An iron stove was installed one third of the way from the entrance and everyone moved to live in the barracks, including the engineers and technicians. Even the families. They simply fenced off their space with some curtains. Life became much better - there were no such wild temperature drops as in the tent, and there was no particular heat either. True, the first weeks were very damp and humid, since all the material from which they built was frozen and damp. It took a lot of time to dry it out. About two weeks after we moved in, I felt some creatures crawling all over my body - I dug around, looked and found - lice. Kamenev found the same thing. It became clear to everyone that the problem of washing people needed to be solved urgently, i.e. build a bathhouse.

We recently started the construction of a new building - a party office and rooms for housing engineers and technical workers. We had to revise the layout and set aside one edge for a bathhouse and an entryway for it. Again, everything was built from frozen damp wood - only the tow for laying the seams between the logs was dry. In 3 weeks, we finished this building too. We installed an iron stove in the bathhouse, but there was still ice on the floor in the entryway - changing room. And in the bathhouse itself, the floor was cold and in order not to freeze, we had to put our feet up on the shelf. In addition, they brought some preparations for sanitizing the dormitory. Some people went to live in the new building. All these measures together gave the desired effect and our lice were completely eliminated. True, there was a small inconvenience - on days when the bathhouse was open, steam from it got into our office through loose joints in the main wall, but we could put up with it.

The majority of the staff, with the exception of families, ate in a common pot. There was a cook who cooked for everyone. The food consisted mainly of canned borscht or soups, if they ran out, then they cooked from dried vegetables - cabbage, potatoes and onions. They often cooked porridge. Of the fresh products, there was always frozen venison. True, once they sent some very thin and black carcasses. We asked for clarification on the radio. Ilyashevich wrote to us that this was second-grade meat, but did not have a marketable appearance. These explanations did not make it any tastier. There were no fresh vegetables in the diet, since there was practically nowhere to store them. Dishes prepared entirely from dried vegetables were hardly edible and resembled a rare nastiness. Apparently, the technology of drying them in those years completely destroyed their natural taste and smell. True, dried potatoes in plywood drums, cabbage and onions in paper bags were very light and transportable.

- 12 -

After some time, the three of us - Kamenev, Kalinin and I - went on a reconnaissance of the uppermost line, 10 km from the party base. This was already above the mouth of the Parnuk river. We went on skis along the left bank of the Khobeyu. River terraces were clearly visible everywhere, which could be like "traps" for placer gold. Kalinin really liked most of the places in the relief of the river valley and he often said that this was a typical gold mine landscape. His experience in such matters, of course, could not be disputed by us then. Kamenev took up this work very actively, although he had never dealt with gold. He studied the literature that he brought with him. He often consulted with Kalinin. He was interested in mine technologies for sinking pits, although at first I myself was a pure theorist in this matter. We all learned and improved our knowledge as the work progressed, trying not to step on the same rake twice. Sometimes we made mistakes, but we did not shift our responsibility onto anyone. Looking ahead a little, it must be acknowledged that the main contribution to the search and exploration of gold placers on the Khobeyu River and its tributaries in the 60s was made by Kamenev V.M., who began with Khobeyu and ended up as the head of the Saranpaul expedition.

... And summer transport too

A good assistant at that time was the foreman-geologist Misha Kuchukov - either a Buryat or an Altai by nationality. He had a good schooling in seasonal field parties, and knew how to get along with the working class. The closing of all the outfits, basically, fell on him. He also supervised the miners. He suffered greatly from toothache, which is why he died early, having received blood poisoning from teeth.

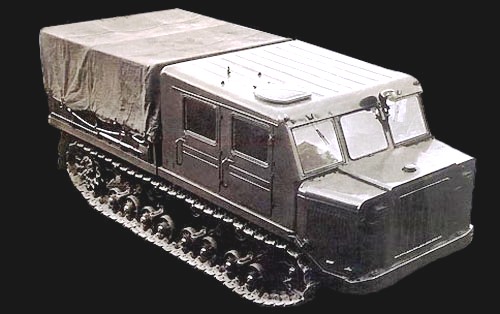

A considerable responsibility lay on the washers of the concentrate samples. Before washing, the rock layouts had to be thawed with fires, and then washed in wooden trays in the river winter water until the concentrate was gray. Then further finishing was carried out until it was black. Nelya Katina did this, sitting in a small tent over the river ice hole. Her hands were constantly red from the cold river water. I decided to try this myself and collected sand from the ice hole at the bottom of the river in a tray. I washed it to a gray state and counted about 200 gold coins. Apparently, the entire Khobeyu basin was "infected" with small, dusty gold. At the end of March, we were informed that the expedition had received 2 light artillery tracked tractors ATL, which had already arrived in Saranpaul and were preparing to leave for Khobeyu with cargo. They told us to report what to bring to us first. Another instruction was to trace the last 10 km section of the route, which ran directly along the bed of the Khobeyu River, to mark the bypasses of dangerous places with thin ice and ice hanging over the water, to meet the tractors on the shore before they entered the ice of the riverbed. It was a very important matter - it was possible to drown not only the cargo, but also the people. Ice on mountain rivers is very treacherous, of uneven thickness, and in some places it hangs in the air, not resting on the water. Its bearing capacity in such cases drops several times.

Crawler tractor ATL-5

We went together with the topographer Dudkin. We decided to trace the river during the day, mark the route of the tractors, and at night go another kilometer down the river and spend the night there in a hut, and meet them on the bank in the morning. I took a gun with me and on kitty skis - forward. Fortunately, there were not many dangerous places, we made ski detours, but we could only guess approximately where on the bank the tractors would appear. In one place along the right bank we saw fresh entrance tracks of an elk into a small coastal forest grove. We looked closely - and in the distance between the bare aspens we saw the animal - it was leisurely eating twigs.

Having walked a little further down the right bank, we sat down to rest. I had the gun on my knees, and my gaze was directed at the river. We sat quietly, not talking. A little later, out of the corner of my eye, I saw some movement on the left. I turned my head and immediately identified it as a wolverine, although I had only seen it in pictures before.

It was slowly moving towards us along our trail. Its head was level with its back, as if it were sniffing the ski trail. It came to a distance of about 30 meters. I could have managed to shoot it, but both barrels were loaded with medium shot, which, given its size - from a small bear cub, was ineffective. Catching my gaze, directed right at it, it abruptly turned off the ski track to the right and immediately disappeared in large leaps into the coastal forest.

- 13 -

Wolverine

Such "carefree" behavior of the animals indicated that people appeared in these places extremely rarely. Moose, as a rule, do not tolerate close human presence and immediately leave the line of sight even before meeting, and the wolverine is an even more cautious predator. Few, even hunters, can tell about meeting her. It was really a very remote corner even for these places.

About a kilometer later we found a hut on the left bank of the river. It was a fairly large hut, chopped from logs, with a disproportionately small iron stove. Moreover, the stove had already burned out in some places and was shining with holes. We went to chop wood - the nights were still quite cold. We melted it. We cooked porridge with stew in a pot, and then brewed tea. When the hut warmed up a little, or maybe it seemed that way to us, we went to bed and tried to fall asleep. We didn't have sleeping bags, so we had a hard night ahead of us. We put out the candle and fell silent. Then some rustling and squeaking began. It turned out to be mice. They had been waiting for our arrival for a long time and apparently had a party on this occasion. They were making noise near us all night, and the stove quickly burned out and the warmth from the hut began to evaporate. In general, we couldn't really get any sleep. Only before the morning, having lit the stove again, we fell asleep a little. After drinking tea and gnawing on frozen sausage, we set off on our way back.

Having reached the place where we had seen the moose, to our surprise, we discovered the tracks of all-terrain vehicles that had descended from the coastal elevation onto the river bed and were going into the distance. There was a Mansi tent covered with skins and an unfamiliar Mansi man was cutting up the carcass of a freshly killed elk - the same one we had seen the day before in this same grove. It turned out that he was driving his reindeer team along a trail made by tractors in the deep snow. And what was unusual was that despite the roar of the tractor engines passing by, the elk never left this grove.

We went back to the base. Our work was not in vain - the tractors followed our trail exactly, without deviating anywhere. It was more difficult to go up the river, so we arrived at the base somewhere around lunchtime. From afar, we noticed two squat beetles standing on the shore with tarpaulin awnings on the cargo area, a car cabin and tracks instead of wheels. The head of the expedition, V.A. Chepkasov, arrived with them. I came closer to examine this miracle of technology. Despite the lack of a road to us, the tractors covered the distance of 80 km in 10 hours, crossed the Polya River and the Devil-Iz Ridge.

ATL is a light artillery tractor, a tracked vehicle weighing about 7 tons and with a lifting capacity of 2 tons. The engine is a two-stroke diesel engine in a forced 135 hp version from the Yaroslavl plant. The drive sprockets are in front, as are the side clutches. As the experience of their further operation has shown, they had a number of major drawbacks, namely: high fuel consumption, cases of the diesel engine running in a "runaway" state, very weak metal of the friction clutch running rollers, poor cross-country ability in winter when climbing hills, rapid wear of the chassis in summer - sprockets and track pins. However, they certainly played a positive role in the further work of the expedition. By the way, one of the ATLs that arrived had already broken down and the driver was disassembling the right clutch. A little later he took out a running roller with completely crushed teeth. Naturally, nothing like this could happen to us and its driver left in another car. The part was brought by plane from Tyumen a few weeks later, the driver flew to us by helicopter, repaired the car and it managed to return to the expedition base on the ice before spring.

Chepkasov inspected the party's base - a residential barracks, an office, a bathhouse and everyone went with him to the work sites. First they inspected here, then went to the second line. He inspected literally all the working objects - the shafts, the work of the washers, the construction of the helipad. Some shafts were already quite deep and water was beginning to ooze out there, which was removed along with the rock by tunneling buckets. Later, when he had finished his business with us, he said that I had to prepare to leave for Saranpaul soon - an avalanche of new matters was starting to accumulate there: registration of permits for storing explosives in the expedition warehouse, a trip to Tyumen to receive two ready-made pumps, receiving and sending explosives, and also it was necessary to look at the affairs of the drilling rig in I.M. Sidoryak's party. Explosives were needed for the field season for the survey parties, which was just around the corner. And the Khobein party needed them for crushing large boulders in the pits. Around the beginning of April, I was summoned to Saranpaul by radiogram.

- 14 -

Chapter 4. Saranpaul. Mansi and Zyryans (Komi). Krasnovskys. Trip to the drilling rig. Berezovo.

There were many Pauls in the Berezovsky district - Yanypaul, Nervatpaul, Suevatpaul, Timkapaul, etc. Paul in Mansi means a large village. This is where the name Saranpaul comes from - a Zyryan large village. With a total population of about 3,000 people, more than 70% were Zyryans and Mansi.

The Zyryans (Komi) came to Saranpaul from areas west of the Ural Mountains, crossing them in the 17th century through a pass called the Sibiryakovsky tract. They still have their own national autonomy there. In Saranpaul, they are engaged in reindeer herding, fishing, and some people work in expeditions. The most common surnames are Rochev, Khatanzeev, Vokuev, Kanev, Filippov, Semyashkin. In general, they are quite numerous throughout the country.

Komi in national costumes