Death in the snow

The Cairngorm Plateau Disaster aka The Feith Buidhe disaster

Sources The Cairngorm Club Journal 095 - The Feith Buidhe disaster WM, "The Courier" Nov 20, 2021, and Wikipedia

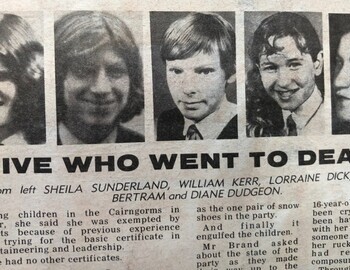

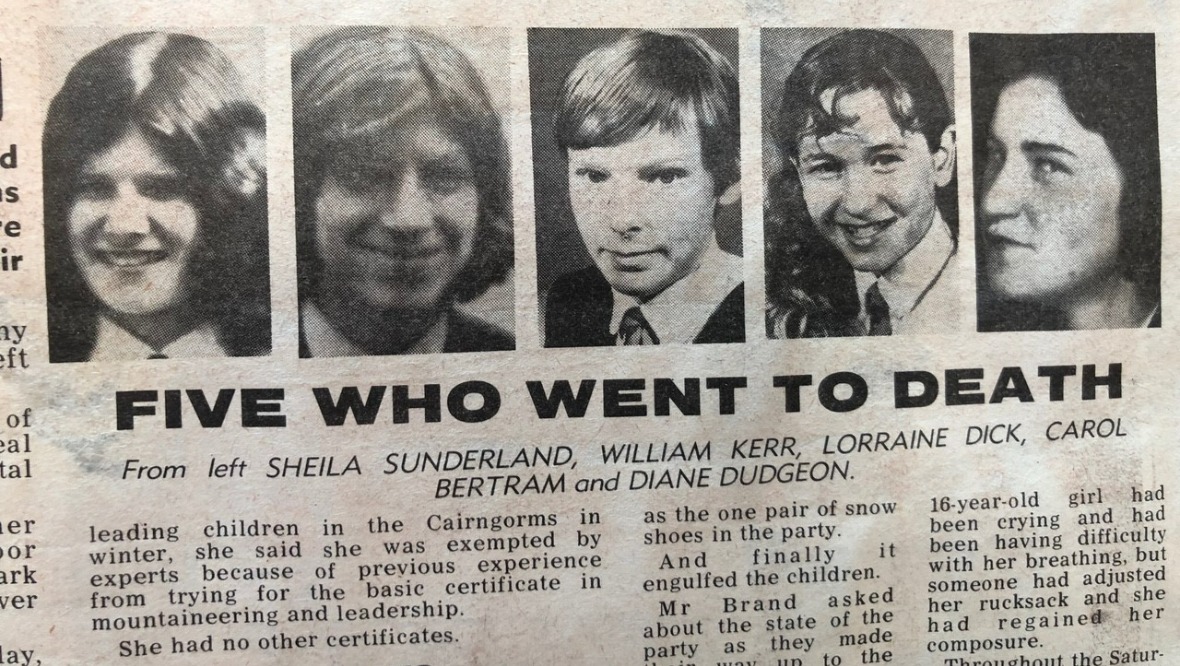

Sheila Sunderland (18), William Kerr (15), Lorraine Dick (15), Carol Bertram (16) and Diane Dudgeon (15)

Susan Byrne (15) is also a victim but no picture of her is found

At 7.25 pm on Sunday, 21 November 1971, it was reported at Aviemore Police Station that a party of six schoolchildren plus a female instructor and a trainee female instructor had failed to return from an overnight expedition in the Cairngorms. This was the first intimation of the Feith Buidhe Disaster - the worst disaster in Scottish Mountaineering history, in which five teenage schoolchildren and the trainee female instructor died, and the two survivors, badly exposed and frostbitten, were saved by a very narrow margin.

Those in the disaster party were as follows:

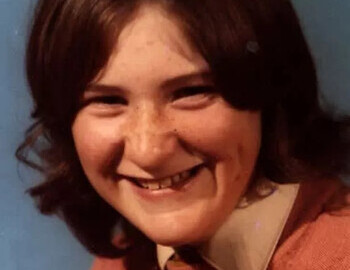

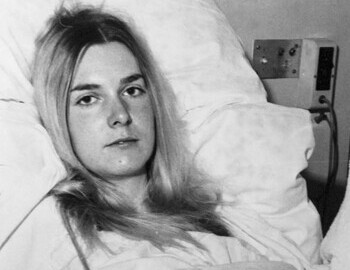

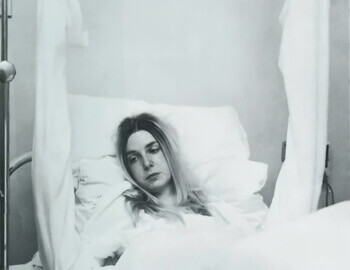

Catherine Davidson (20), Student Physical Education Teacher - survived

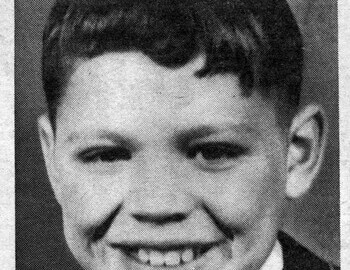

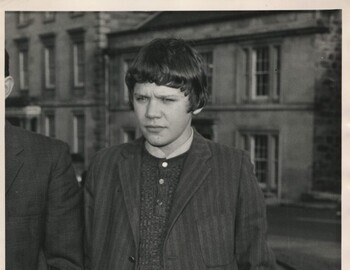

Raymond Leslie (15), Schoolboy - survived

Sheila Sunderland (18), Student - died

Carol Bertram (16), Schoolgirl - died

Diane Dudgeon (15), Schoolgirl - died

Lorraine Dick (15), Schoolgirl - died

Susan Byrne (15), Schoolgirl - died

William Kerr (15), Schoolboy - died

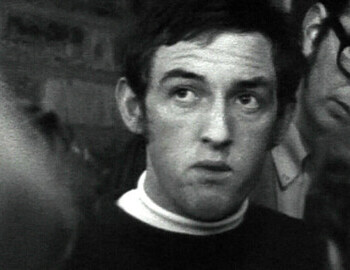

About 10 pm on Friday, 19 November a party of fourteen school-children from Ainslie Park School, Edinburgh, in the charge of Ben Beattie (23), an Instructor of Outdoor Education, and accompanied by Catherine Davidson, and Sheila Sunderland, arrived at Lagganlia Center for Outdoor Education, Kincraig. Lagganlia is an outdoor center administered by Edinburgh Education Authority, with a resident Principal, Mr John Paisley (39). Catherine Davidson, Beattie's girlfriend, was there in the capacity of an instructor, and Sheila Sunderland, whose first visit this was to the Cairngorms, was to be working at Lagganlia Center as a Voluntary Instructor for three weeks.

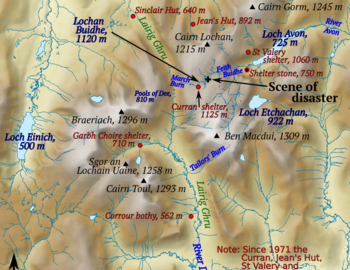

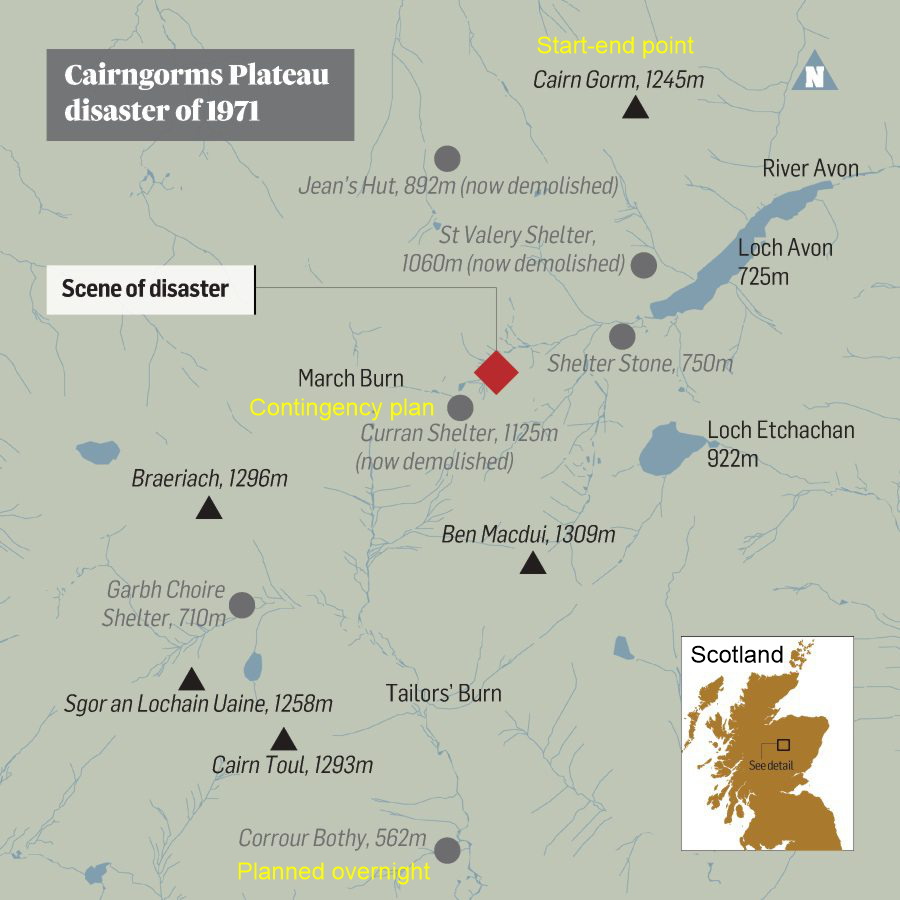

The purpose of the visit by the Ainslie Park School party to Lagganlia was to practice navigation and emergency bivouac techniques on the Saturday and the Sunday, but on arrival at Lagganlia the bivouac plan was changed to spending the Saturday night in Corrour Bothy (bothy = shelter). The planned route was as follows:

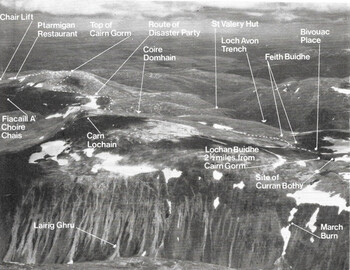

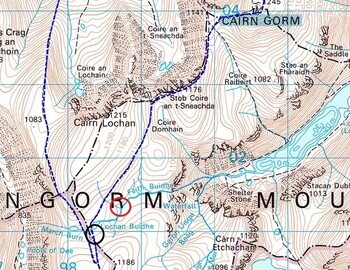

Outward Cairngorm Car Park - Fiacaill a' Choire Chais - Cairngorm - Lochan Buidhe - Ben Macdhui - Allt Clach nan Taillear - Lairig Ghru - Corrour Bothy.

Alternative Bivouac at Curran Bothy at Lochan Buidhe.

Inward Corrour Bothy - Cairn Toul - Braeriach - Sron na Lairig - Coire Gorm - Sinclair Hut, Rothiemurchus.

Alternative Lairig Ghru - Sinclair Hut.

The plan was to cross the Cairngorm plateau, from Cairngorm to Ben Macdui, spend the night in the low level Corrour Bothy and return to the center on Sunday.

The party was to be split up into two groups, the older and stronger group under Beattie, and the younger and weaker group under Davidson, with Sunderland accompanying the second group, partly to assist, but mainly to gain experience.

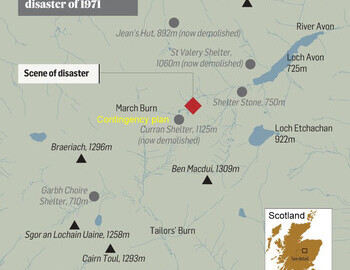

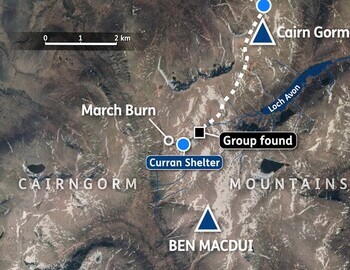

Map of central Cairngorms showing shelters and features relating to the 1971 disaster

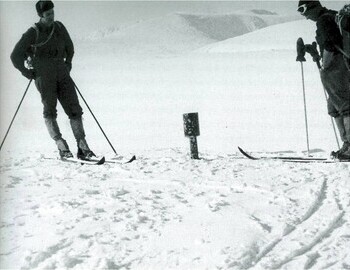

On the Saturday morning, November 20, 1971, the combined party left Lagganlia between 10.30 am and 11 am and drove to Cairngorm car park. At this time there was snow on the ground, and the forecast was of deteriorating weather, with snow.

At the car park, the plans were modified, and both groups took the chair lift to the top station, going to the Ptarmigan Restaurant, where they ate their lunch. Beattie, with eight children left about 20 minutes before Davidson and Sunderland with six children.

- 2 -

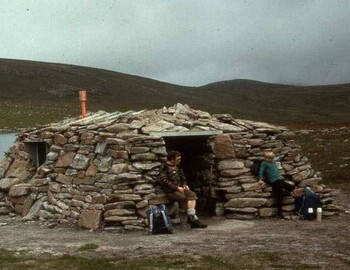

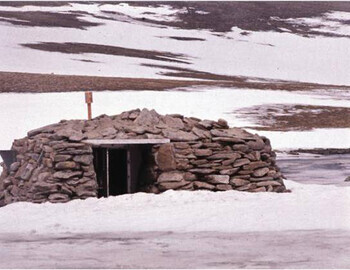

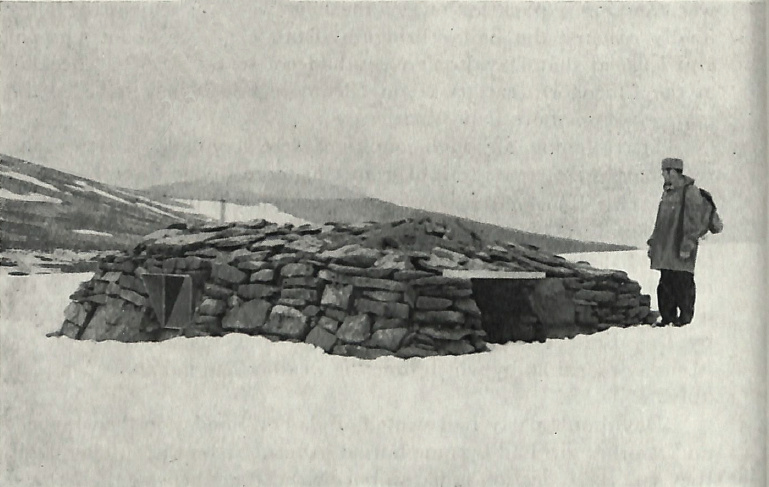

Beattie's party had a fairly uneventful walk to Curran, but were faced from Coire Domhain on with increasing wind and lessening visibility, forcing them to navigate by line bearings. They arrived at Curran Bothy about 3.30 pm, having decided to implement the bad weather alternative plan and stay there overnight. When the second party did not arrive, they assumed that Davidson had gone to the St Valery refuge or to Jean's Hut, as these had apparently been mentioned earlier. They were not worried about their nonappearance, and spent what must have been a cold and uncomfortable night in the bothy.

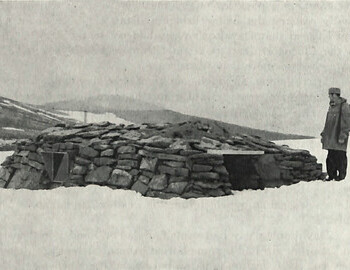

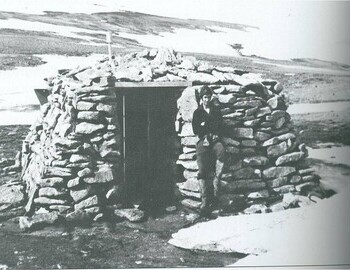

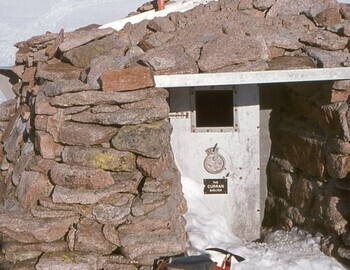

The Curran Bothy in early June 1972, still with about 4 feet of snow. It was not possible to open the door till midsummer day. Photo by J. Duff

The Curran Bothy covered by about 7 feet of snow in early March 1972. Only the ventilator is visible. Photo by D. Grieve

When Davidson's party left the Ptarmigan Restaurant, they climbed Cairngorm, and left the summit for Curran, according to a Glenmore Lodge Instructor who was working at the radio station there, at about 1.20 pm. They encountered bad conditions in Coire Domhain, with knee-deep snow and a strong SSE wind. In the Feith Buidhe basin the snow conditions were worse, and Davidson took the party to the Feith Buidhe stream (buidhe = stream = burn), hoping to follow it up to the Lochan Buidhe and so to Curran Bothy. This proved to be impossible, as the stream was completely covered over by snow, and as dusk was rapidly approaching, Davidson decided to bivouac where she was rather than to risk tiring out her party in a possibly vain attempt to find the Curran Bothy. The snow was floury, and useless for snow holing, and they eventually lay down behind a makeshift wall of snow. They removed most of their wet clothing and got into their poly bags and sleeping bags.

During the Saturday night, the weather worsened and the party started to become buried by drifting snow. Some of them panicked, and Davidson did her best to dig them out, losing her mitts in the process. At first light on the Sunday, Raymond Leslie was completely buried but could still be heard, and two of the girls were lying on the surface, out of both their sleeping bags and poly bags. Another girl was described as being 'in a bit of a daze'. It seems likely that these three girls were already dying of cold.

Davidson got the two uncovered girls back into sleeping bags, and, along with William Kerr, who appears at this stage to have been still quite strong, tried to go for help. This effort was abandoned, however, after about 25 yards, because of thigh-deep snow and strong wind. They returned to the bivouac and waited, hoping that the weather would improve.

On the Sunday morning, Beattie's party, still assuming that Davidson was at St Valery or Jean's Hut, found the weather considerably worse. They had difficulty in getting out of the Curran Bothy because of the door being jammed shut with snow. They descended the March Burn to Lairig Ghru, the descent involving a commando abseil during which one boy slipped and almost fell. Beattie had to fit crampons to the children's feet, and one boy cried because he was scared. In Lairig Ghru conditions were still very bad, and it was not till about 3 pm that they reached the Sinclair Hut. By this time Beattie was carrying a pack for one of the boys who was exhausted. They finally reached the Bailey Bridge at Rothiemurchus about 5.30 pm and learned that Davidson's party had not returned. After checking at the Cairngorm car park and Glenmore Lodge they reported the matter at Aviemore Police Station.

That evening, although conditions were very bad, three two-man reconnaissance parties set out from Glenmore Lodge to probe-search likely areas. This search was fruitless, and in fact the conditions were so bad that the parties completely failed to find the St Valery refuge, and had to search for the Shelter Stone. One party returned to Glenmore Lodge, and the other two spent the remainder of the night at the Shelter Stone. The reflection of flares set off by these parties was seen by Davidson. The search was resumed on a massive scale on the Monday morning, by which time the weather had improved considerably.

Davidson's party had waited all day on Sunday in their bivouac and another girl had become buried. After dark on the Sunday night, they saw the reflection of flares, but by this time their own mini flares were lost and they could not reply. The party was now in dire straits, and probably some were already dead.

At daybreak on the Monday, Davidson and Kerr again tried to go for help, but the boy was too weak and collapsed.

- 3 -

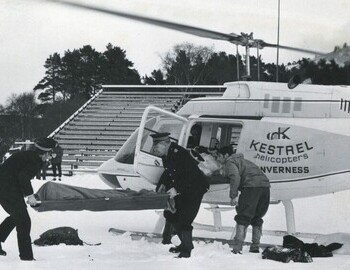

The tragic day on the plateau with the troops and the Jet Ranger helicopter

In stormy but moderating conditions on 22 November 1971, 50 men were searching with helicopter support. In the morning, the Braemar MRT, travelling from the south, reached Corrour Bothy, only to find it unoccupied. It was at about 10:30 that Davidson was spotted from a helicopter. The Whirlwind helicopter had been dispatched from RAF Leuchars in Fife, and the pilot attempted to fly up the line of Glen Shee, but turbulence meant that he had to reduce airspeed to 70 knots (130 km/h; 81 mph), with ground speed less than walking pace. At Pools of Dee, he was reduced to a hover and was unable to ascend to the plateau and so he took a wide detour to Glenmore Lodge. There, the crew was asked to make an airborne check of various shelters, without any delay for refueling. At the Curran shelter, there was nothing to be seen, but as they turned to go back to Glenmore Lodge, they spotted what they thought was a red tent.

Edging closer and without reference points in the whiteout, they realized that they had got very close to a person on her hands and knees. Davidson was still up on the plateau and trying to crawl for help. Two crew were unloaded 64 meters (70 yd) away, the closest they could manage. Then, they reached the casualty but could not carry her to the helicopter because her legs were locked in a kneeling position. The helicopter could get no closer because when it applied power, the blowing snow obliterated vision and so one of the crew jumped out to lead it in the right direction by using the winch wire. There was no sign of anyone else from Davidson's group. Davidson was taken by helicopter to Aviemore, where she was met by ambulance. Hypotermic and badly frost-bitten, the student teacher was crouched on her hands and knees in a futile bid to seek refuge from the relentless battering of the screaming winds and bullet -hard snow. By the time the search team reached her, she was so weak from her ordeal that she could only manage four words: "Feith Buidhe', 'burried', 'burn'*. Other sources say the words Davidson could manage were "Burn – lochan – buried". Lochan Buidhe and Feith Buidhe are both streams (burns) where approximately the bivouac and the buried in the snow children were.

[* In the Scottish Highlands, a "burn" refers to a small stream, creek, or small river, a common feature of the landscape, often fast-flowing and fed by rain, and a word deeply embedded in local place names and common speech, differing from the English "brook" or "creek". It's a natural, flowing watercourse, smaller than a river but larger than a ditch. See a photo of a burn in Cairngorm]

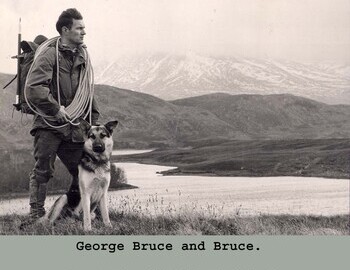

By then, the cloud base had become lower, and no helicopter could get nearby, but several search teams on foot converged on the location of the catastrophic bivouac through snow sometimes waist deep. The Glenmore Lodge instructor John Cunningham along with Beattie and Paisley were the first to find the scene. The bodies of six teenage students and the assistant were dug out, one from a depth of 1.2 meters (4 ft). All were dead except the last person to be uncovered, Raymond Leslie, who was still breathing. He was cared for by a doctor from the Braemar MRT on his first serious call-out. At 15:00, a Royal Navy Sea King helicopter arrived, guided by the leader of the RAF Kinloss MRT walking ahead firing flares. Leslie, the surviving boy, was airlifted to Raigmore Hospital, where he and Davidson eventually recovered. Some of the instructors from Glenmore Lodge had been out for 20 hours so, in the darkness, the dead were left on the mountain to be brought down the next day.

About 12.30 pm the position of the buried party was established and between then and 1.30 pm all the buried children were found. The last to be found was Raymond Leslie, who was still alive although unconscious and badly frostbitten. He was buried under four feet of level snow. He was flown by helicopter to Raigmore Hospital and subsequently recovered.

By the time all of the party had been found and the survivor evacuated, it was too late in the day to start evacuation of the bodies, so that it was the Tuesday before they were finally flown off the hill. All of the flying was carried out in extremely marginal conditions.

A Fatal Accident Inquiry was held in Banff in February 1972, and it lasted for six days. The jury returned a formal verdict and did not allocate blame, but made the following recommendations:

The Jury state that they would not discourage the spirit of adventure in outdoor activities with children, but they suggest the following recommendations from the evidence before the Inquiry:

- That more care be exercised in the organizing of parties of young children in outdoor activities with special regard to fitness and training.

- That fuller information regarding outdoor activities should be given to parents and acknowledged by them.

- That certified teachers should accompany their pupils to outdoor centers such as Lagganlia and that expeditions should be led thereafter by fully qualified and long experienced instructors in their own field. This includes references to weather forecasts and local conditions.

- That certain areas of the countryside be designated as suitable for children's expeditions in summer and winter. These areas to be decided after consideration with the Scottish Mountain Leadership Board, Mountain Rescue Organisations and local knowledge.

- In the matter of high level bothies, advice as to their removal or otherwise should be left to the experts.

- That they endorse what the Court said in praise of Mountain Rescue Operations and suggest that thought might be given to furthering the good work done by them, financially and otherwise.

- In the event of a disaster closer liaison should be kept between authorities and parents concerned.

Arising out of item 5 above, the following important notice has been widely displayed and publicised, although, due to certain objections being raised, the removal of the bothies has been delayed. It seems likely, however, that the notice will still be valid, as the bothies will very probably have been removed by the end of this summer.

Following a decision made after the fullest possible consultation, the bothies known as:

CURRAN situated beside Lochan Buidhe at MR 983010

EL ALAMEIN on North Ridge of Cairngorm at MR 016054

and

ST VALERY on the cliffs above the west end of Loch Avon at MR 002022

are to be removed on 2nd June 1973 or as soon as possible thereafter. It is most important that no plans be made involving the use of any of these three bothies after 2nd June 1973.

| TOM CHASSER | A.L. McCLURE |

| Chief Constable | Chief Constable |

| Scottish NE Counties Constabulary | Inverness Constabulary |

Cairngorm Mountain Rescue Archive Film

- 4 -

Dead before they set off

Diane Dudgeon’s father had no idea the plan was to spend a weekend in the Cairngorms; he thought she was going on a trip around the Lagganlia center. Another parent believed his son was going canoeing.

"They were virtually dead before they set off," said John Duff at the time. "It was simply a badly planned expedition."

Officials tried to find out why the six died 3,000 ft up near Feith Buidhe (Yellow Stream) between Ben Macdui and Cairngorm.

A six-day inquiry into the tragedy in Banff returned a formal verdict, with no blame apportioned, though recommendations were made and regulations on school trips were tightened.

Some wanted to blame the bothies, and calls were made to demolish the Curran and other high-level shelters.

After the tragedy, Catherine moved to Canada and never spoke publicly about her ordeal.

Expedition leader Ben died in a climbing accident in the Himalayas in 1978. Meanwhile, Raymond has never discussed what he went through. Ainslie Park School closed in 1991.

Woefully unprepared

Heather Morning, mountain safety advisor with Mountaineering Scotland, believes the group was "woefully unprepared, inexperienced, ill-equipped and made a huge amount of errors."

"The Cairngorm disaster was a major catalyst which moved the whole system forward to recognize that those taking young people into the hills needed to get training, qualifications and experience," she says.

In 1964, a mountain training award had been launched, but seven years on, it was very much in its infancy.

"Looking at the route they planned, even if you had been a fit, strong, competent winter mountaineer, let alone a bunch of young kids, it would be extremely challenging and potentially put you in some very avalanche prone terrain.

"They set off at midday with just four hours of daylight left. We have much better resources for planning today with avalanche and detailed weather forecasts at the high tops – things definitely not available then. But there’s no doubt a huge amount of mistakes were made."

Some tabloids had a "field day" with the story, says Heather, with headlines such as "Wilderness of Death" and "Snow Tomb" dominating front pages.

On the subject of high-level shelters, Heather describes the Curran as "a bit of a siren", adding: "Arguably if it hadn’t been there, the group wouldn’t have been heading there."

The Curran had been built in memory of the 51st Highland Division by Artificer Apprentices from HMS Caledonia, Rosyth, led by Command Sergeant Major Jim Curran of the Royal Marines.

Heather was saddened when on meeting Jim years after the tragedy he felt compelled to declare: "It wasn’t my fault."

"He clearly harboured feelings of guilt for decades, which was so sad," she laments.

Shaun Roberts, principal of Glenmore Lodge near Aviemore, says the loss of life has an emotional impact 50 years on.

"I have no doubt that when I started my outdoor career in 1991, our framework of 'good practice' was influenced by this incident and the subsequent inquiry," he reflects.

"Today we have specialized mountain weather forecasts with hourly updates, accessible from handheld devices. We have robust risk assessment and management governance. We have highly-developed mountain leadership qualifications and a high class workforce. We have Gps-location devices and satellite communication.

"However, the Cairngorm plateau has the potential to be one of the most inhospitable places on the planet and we continue to work to ensure people are aware of the risks posed by Scotland’s mountains."

George Mcewan, executive officer for Mountain Training Scotland, says while the tragedy underscored the need for having qualified leaders with extensive experience, unexpected events and emergencies do happen.

"Even the most experienced people can get caught out," he says. "This time of year often catches people out. Clocks change and winter can come roaring in with little notice. Even with forecasts, mountains do strange things to weather."

- 5 -

A very different era

Lagganlia opened in 1970, the year before the Cairngorm disaster. Principal John Paisley was in charge of the center through the tragedy and until the mid-1980s.

Today’s principal Nick March is keen to stress that the early 1970s was a “very different era” with outdoor centers "very different places to what we know now".

"There were no qualified staff; rather, you were qualified through experience," he says. "There was no duty of care or the big safety network that we've become so normalized to.

"The school group came from Edinburgh and was led by a really good outdoor education teacher (Ben Beattie) from within the school. Lagganlia's connection was as the place of residence. It gave the school group a place from which to base themselves on outdoor adventures."

Nick says the tragedy led to the biggest rethink of “competencies” for outdoor leaders and led to the "building blocks" that Lagganlia, and all outdoors centers, are built on today.

"What we have in this country now is the safest framework for leaders and instructors to get qualified and for outdoor centers to give a rich framework for bringing future generations to Lagganlia.

"These days we plan what we think is an appropriate adventure for a particular group. It’s not fair to judge what happened in 1971 by what happens today, so I don’t want this to be a criticism but if I was to send those children out, at that age, on that route journey now, it would be seen as a completely inappropriate journey.

"That’s because I sit on the shoulders of all the learnings from that accident, and all the training courses I’ve been through since. I'm a product of a world built on the implications of the incident.

"Out on a mountain, in winter, at that altitude, at that time of year, the volume of unknowns outwith your control – weather, snow conditions, avalanche, remoteness, temperature – are so much higher and is it appropriate to expose anyone, let alone young people, to that environment?

"In today’s world, we'd say absolutely not. But back then was a different era. Today we have 50 years of knowledge."

Memorial

Ahead of the 50th anniversary of the tragedy, Nick spoke to various family members linked to the disaster who say they hold no blame for what happened.

"They want this to be a commemoration of loved ones and not a stone-throwing, finger pointing exercise because they went through that 50 years ago,” he adds.

After the tragedy, John Paisley, also a craftsman, created a memorial in Lagganlia's grounds – a triptych wooden bench.

During lockdown, his sons John and Rob noticed this was "looking 50 years old" and worked together with Nick to create a new one, using pieces of the original. This was unveiled on November 15 at a small remembrance event.

A memorial plaque with the names of the six who died will be added to the bench next year.

Tomorrow, November 21, at Edinburgh’s Granton Parish Church, a formal commemorative service is planned.

"Never a week goes by that the tragedy isn't mentioned at Lagganlia," says Nick. “We talk about it, about how young people that come here are taking part in risk-based activities and how we manage that.

"It’s our responsibility to share that risk with them in a controlled way. And we want the families to know their loved ones will never be forgotten."

Raw reality

The scars of that horrendous November weekend, 50 years ago, are still painful for many.

George Mcewen says while for many the tragedy is a “historical narrative”, for the families of those who lost loved ones, and for those who recovered the children's bodies, it remains a "raw reality".

Former RAF mountain rescue member David "Heavy" Whalley says we must never forget those who risked everything to try to save the children, adding: "That kind of tragedy stays with you forever."

The Cairngorn Plateau 1971 Disaster

Deadly Passes