Microclimatic examination of the Kholat Syakhl mountain area for January-February 1959

Main Geophysical Observatory named after A.I. Voeikov

194021 St. Petersburg, st. Karbysheva, 7

Received by the editors on July 20, 2020

Introduction

In 2019, the Sverdlovsk Region Prosecutor's Office began an investigation into the death of the hikers from Igor Dyatlov's group in the area of Mount Otorten in the Sverdlovsk Region on February 2, 1959. In order to conduct a comprehensive and objective investigation, the head of the Department for Supervision of Compliance with Federal Legislation of the Sverdlovsk Region Prosecutor's Office, Justice Advisor Andrey Kuryakov, decided to involve specialists from the Federal State Budgetary Institution "Main Geophysical Observatory named after Voeikov" (hereinafter referred to as MGO) in the investigation and to appoint a special microclimatic examination of the Mount Kholat Syakhl area for January-February 1959.

This article presents the results of a microclimatic expert study carried out by the author and provides scientifically based answers to the questions posed by the prosecutor's office.

1. Background information

Mount Kholat Syakhl (Dyatlov Pass) is located in the central part of the Northern Urals, which is characterized by a typical mountain climate. This region is very complex, impassable and poorly studied. The illumination of mountainous areas in meteorological terms is extremely insufficient: the nearest station Polyudov Kamen is located in the western foothills of the Urals at an altitude of 529 m above sea level. The only high-mountain meteorological station in the Urals (Taganay-Gora, 1102 m above sea level) is located in the Southern Urals at a latitude of 55.4°, i.e. more than 600 kilometers south of Dyatlov Pass. Other meteorological stations (with low altitude) are located to the west and east of the mountain range, i.e. in the Pre-Urals and Trans-Urals, their data differ significantly in all climatic parameters from the intra-mountain territories, including the area of Mt Kholat Syakhl. In specific areas of the mountainous relief, detailed spatial distribution of climatic characteristics without conducting special microclimatic observations can only be obtained by indirect methods. The MGO developed quantitative methods for assessing the spatial variability of various climatic indicators for hilly and mountainous terrain with limited meteorological information, which were used for a detailed microclimatic assessment of the study area (Pigoltsina, Zinovieva, 2009).

The initial information for calculating the microclimatic variability of climatic indicators and assessing the microclimate in the area of Mount Kholat Syakhl for January-February 1959 was found in the materials provided by the Sverdlovsk Region Prosecutor's Office: surface weather maps, baric topography maps and a composite climatic map for the period under consideration, tables of meteorological observations at the Ivdel, Burmantovo, Vizhay stations, tables of aerological observations at the Ivdel station, cartographic and other analytical materials, including the opinion of an expert glaciologist. Archival materials of the Main Geophysical Observatory on daily data from nearby meteorological stations located in the Sub-Urals and Trans-Urals were also used.

2. Brief characteristics of the synoptic situation from January 31 to February 2, 1959

During this period, the area of the city of Kholat Syakhl was in the zone of influence of a large cyclone, the center of which on January 31 was located to the north of the study area over the Subpolar Urals and then moved from the northwest to the southeast. As a result, cold atmospheric fronts passed over the study area one after another.

The passage of the cyclone caused snowfalls and blizzards. All three days there was continuous continuous snowfall of varying intensity - from light to heavy. The snowfall was accompanied by ground blizzards, fogs with hoar frost. According to calculations, at least 10 mm of precipitation fell on the plateau of Mount Kholat Syakhl (altitude about 1000 m) in two days (January 31 - February 1). The snowfalls were accompanied by strong winds. The wind speed on the plateau for three days was 10-15 m/s, while the temperature fluctuated from -10 to -33 °C.

3. Microclimatic characteristics of the Kholat Syakhl mountain area

The calculation of meteorological indicator values and the microclimatic characteristics of the area were performed for the period from 13:00 on February 1 to 19:00 on February 2, i.e. for the period including the time of arrival of the hikers on the slope of Kholat Syakhl mountain and the following day.

- 2 -

3.1. Air temperature

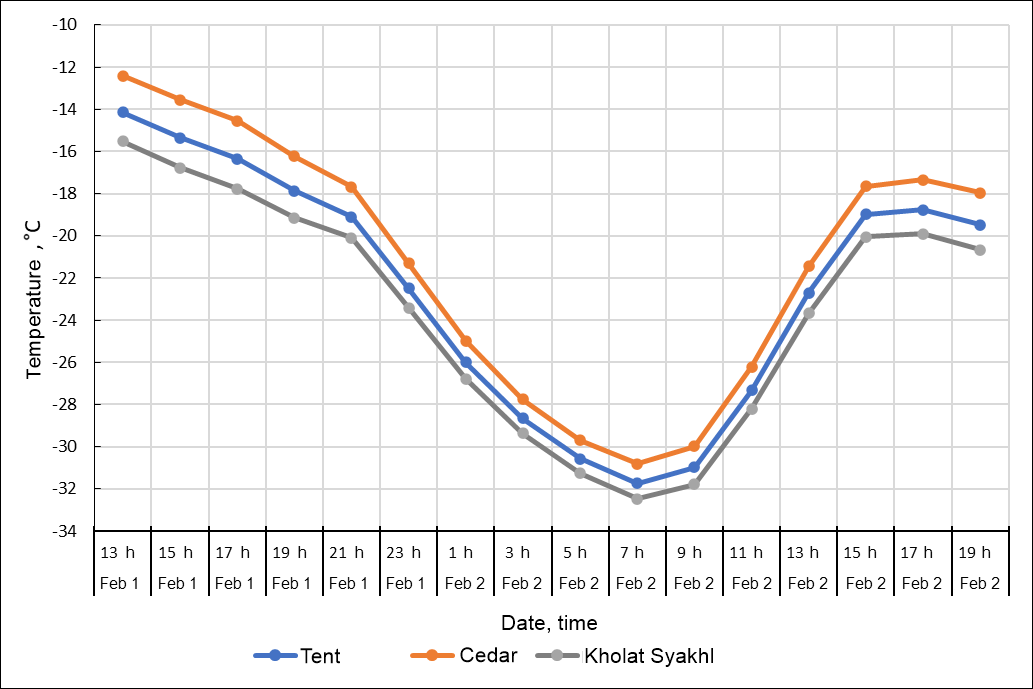

The thermal regime of mountainous terrain depends mainly on the absolute height above sea level and the relief shape. Due to their influence, temperature characteristics can change significantly over a distance of several hundred or even tens of meters. For the area under consideration, the air temperature was calculated for three points:

1 — the summit plateau of Mount Kholat Syakhl, which is located above the 1080 m isohypse (i.e. for an altitude of 1080-1090 m);

2 — for the tent site (altitude of about 894 m);

3 — the cedar area (altitude of 630-640 m).

The results obtained are presented in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Table 1

Air temperature (°C) in different points of the Kholat Syakhl region

| Date | Time, h | Location of points | ||

| plateau | tent | cedar | ||

| Feb 1 | 13 15 17 19 21 23 |

–15,5 –16,8 –17,8 –19,1 –20,1 –23,4 |

–14,1 –15,4 –16,4 –17,9 –19,1 –22,5 |

–12,4 –13,5 –14,5 –16,2 –17,7 –21,3 |

| Feb 2 | 1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 |

–26,8 –29,4 –31,3 –32,5 –31,8 –28,2 –23,7 –20,0 –19,9 –20,7 |

–26,0 –28,7 –30,6 –31,7 –31,0 –27,3 –22,7 –19,0 –18,8 –19,5 |

–25,0 –27,8 –29,7 –30,8 –30,0 –26,2 –21,4 –17,6 –17,3 –18,0 |

The graph clearly shows the change in air temperature during the period under consideration at different points on the slope. On the slope, there is a regular decrease in temperature with increasing altitude. The lowest temperatures correspond to the summit plateau, further down the slope the temperature increases, although the temperature differences between the summit plateau and the location of the cedar are small, since the difference in absolute altitudes between these points is relatively small (less than 500 m). The largest differences in temperature between these levels occur during the daytime and reach 3.2°C. At night these differences do not exceed 2° with a minimum at 5 am (1.5 °C).

Fig. 1. Daily variation of air temperature (°C) on February 1 and 2, 1959 at three points in the Kholat Syakhl area.

From the documents presented by the Sverdlovsk Region Prosecutor's Office, it follows that the group of hikers arrived at the tent site on February 1 at 5-6 pm and settled into the tent at 7-8 pm. At 18:00 the temperature at the tent site was -17°C, at 20:00 -18.5°C. It was at this time that a cold front passed over the area, and the influx of cold air led to a sharp drop in temperature. The temperature at the tent site was already -22.5 at 23:00, -28.7 at 3:00 at night, and by 7:00 in the morning it had dropped to -31.7°C (Fig. 1).

3.2. Wind speed and direction

Brief climatic characteristics. In the region under consideration, there is a clearly expressed westerly transfer in the troposphere in the winter. The meridionally elongated mountains have a significant effect on circulation processes, acting as a barrier to the prevailing western transfer of air masses. Under the influence of the Ural Mountains, air flows are deformed, and in the surface layer at this time in the Cis-Urals, southern and south-western (SW) winds prevail (30-50% of cases), and in the Trans-Urals, SW and western winds (30-50% of cases). On the summit open plateau of Mount Kholat Syakhl, westerly winds prevail, the frequency of which in winter (December-February) is 63-64%. The second place in frequency is occupied by SW winds (21-22%). At this altitude (≈1000 m) the speeds are significant throughout the winter, with the frequency of speeds over 10 m/s in January and February averaging 60–62%, and the frequency of speeds over 15 m/s 56–57%.

- 3 -

The average number of days (in January and February combined) with wind speeds over 15 m/s is 32-33, with speeds over 20 m/s - 25-26, with speeds over 25 m/s - 11-12 days. Once a year, wind speeds of 44 m/s are possible, once every 5 years - 50 m/s. Calm weather (number of days with calm) averages only 4 days in January and February. When fronts pass, wind gusts can reach 30-35 m/s or more (Scientific and Applied Handbook…, 1990; Methodical Recommendations…, 1973; Orlova, 1962).

Microclimatic characteristics. A complex combination of relief forms distorts the direction and speed of the wind. Passes create favorable conditions for strengthening the wind, while valleys create mainly conditions for weakening it, but when the direction of the valley and the air flow coincide, the wind can strengthen. When the wind is directed perpendicular to the valley, a zone of low wind speeds arises, the so-called aerodynamic or wind shadow. Wind speed also decreases on leeward slopes.

On February 1 and 2, 1959, according to aerological and synoptic data, a northwest (NW) wind blew over the mountains (at an altitude of 1000-1100 m). Based on the analysis of the hypsometric map, it can be stated that on the north-north-eastern spur and on the eastern slope of Mount Kholat Syakhl (including the site of the tent) and in the area of the cedar, the wind also had a NW direction. In this small area, the wind direction could change directly on the saddle of the Dyatlov Pass, but this does not matter for assessing the wind characteristics at the site of the tent and the cedar.

Thus, the microclimatic variability of wind speed was calculated under the condition that the wind had a NW direction and blew from the north-north-eastern spur of Mount Kholat Syakhl, and the tent, therefore, was on the leeward slope in the wind shadow zone. Moreover, the tent was pitched in the immediate vicinity of the zone of maximum snow accumulation between the spur and the tent (which will be discussed below), forming a powerful snowdrift (snow pile) above the tent, which enhanced the effect of the tent's protection from the wind.

From the above, it follows that the hikers stopped and pitched the tent in a place on the slope where a wind shadow was observed, that is, a decrease in the wind flow power by 10-15 % relative to the surrounding area was observed. It should be noted that the tent was pitched with the entrance on the leeward side.

Wind speed for different sections of the terrain was calculated using a well-known method: at the first stage, the change in wind speed was determined depending on the altitude above sea level (the so-called background wind speed values), then microclimatic corrections were introduced, taking into account the location of a specific section in the terrain and the wind direction (Methodological recommendations ..., 1973; Orlova, 1962; Microclimate of the USSR, 1967; Pigoltsina, Zinovieva, 2014).

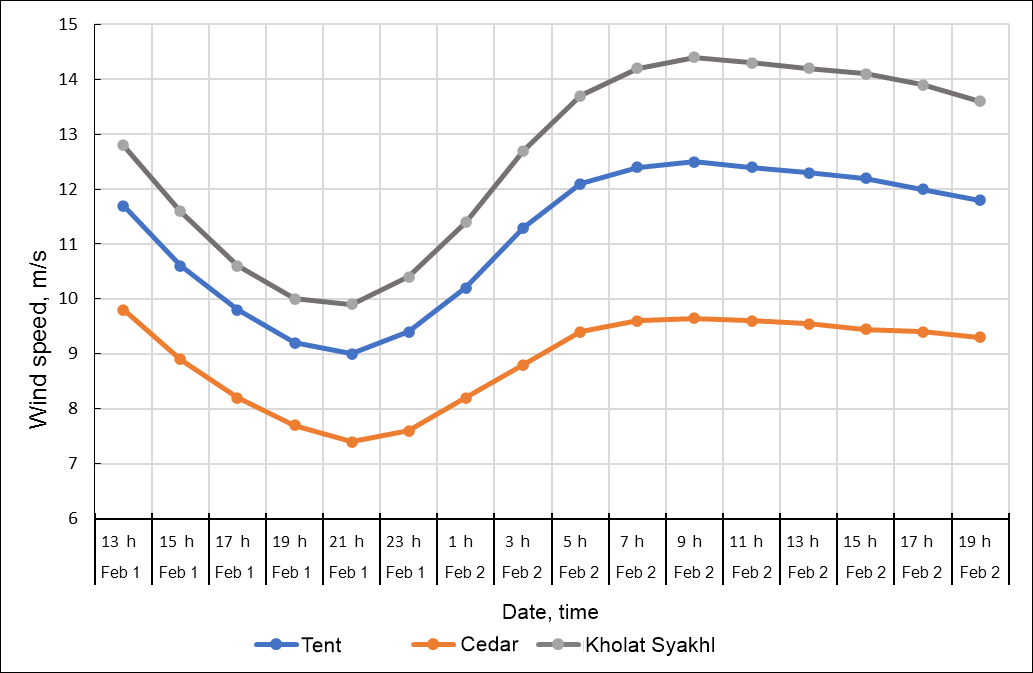

Fig. 2. Daily variation of wind speed (m/s) on February 1 and 2, 1959 at three points in the Kholat Syakhl area.

- 4 -

When calculating the wind speed, observation data were used for the periods, and no wind gusts were observed during these periods. Stations are often unable to record wind gusts, since these are short-term phenomena that can occur between observation periods. However, it should be noted that when cyclones pass over the Subpolar Urals, similar to our case, when a sharp increase in wind and snowstorms are observed, gusty winds are not uncommon (Orlova, 1962). The results of calculating the wind speed are presented in Figure 2 and Table 2.

Table 2

Wind speed V (m/s) at the points in the area under consideration

| Date | Time, h | Location of points | ΔV | ||||

| plateau | tent | cedar | Vtent – Vcedar | ||||

| Feb 1 | 13 15 17 19 21 23 |

12,8 11,6 10,6 10,0 9,9 10,4 |

11,7 10,6 9,8 9,2 9,0 9,4 |

9,8 8,9 8,2 7,7 7,4 7,6 |

1,9 1,7 1,6 1,5 1,6 1,8 |

||

| Feb 2 | 1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 |

11,4 12,7 13,7 14,2 14,4 14,3 14,2 14,1 13,9 13,6 |

10,2 11,3 12,1 12,4 12,5 12,4 12,3 12,2 12,0 11,8 |

8,2 8,8 9,4 9,6 9,7 9,6 9,6 9,5 9,4 9,3 |

2,0 2,5 2,7 2,8 2,9 2,8 2,8 2,8 2,6 2,5 |

||

During the day, the highest wind speeds are naturally observed on the open summit plateau. Down the slope, the wind speeds decrease and in the cedar area (in the stream valley) they have minimal values.

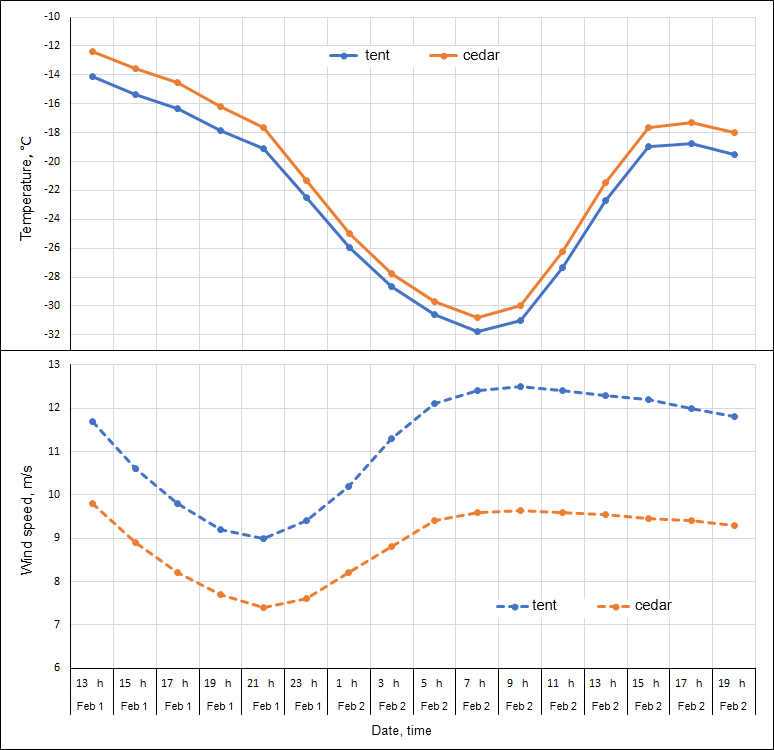

The graph (Fig. 2) clearly shows that after the passage of the cold front (which was mentioned above), from 9 pm on February 1, the wind speed increases sharply. The temperature graphs (Fig. 1) and wind speed (Fig. 2) agree well. For better visualization, these graphs for the tent and the cedar are combined in Fig. 3. From 9 pm, the temperature begins to drop sharply, and the wind speed increases. The lowest temperatures were observed at maximum wind speeds.

Fig. 3. Diurnal variation of air temperature and wind speed on February 1 and 2, 1959 at the locations of the tent and cedar.

3.3. Wind chill index

Staying in the cold for too long can lead to frostbite, hypothermia, and ultimately death. Strong winds at low temperatures increase the effects of the cold. The impact of weather conditions on a person is assessed using the method of complex climatology, in which the analysis of weather conditions is carried out not by individual meteorological factors (temperature, wind, humidity), but by their complex.

The wind-chill index is used to assess the severity of winter weather conditions. This index allows one to quantitatively take into account the impact of wind on the human body at different air temperatures. The cooling force of the wind affecting the tissues of the body is expressed as a temperature equivalent, and the wind-chill index is measured in a conventional temperature equivalent, that is, in degrees Celsius (°C).

- 5 -

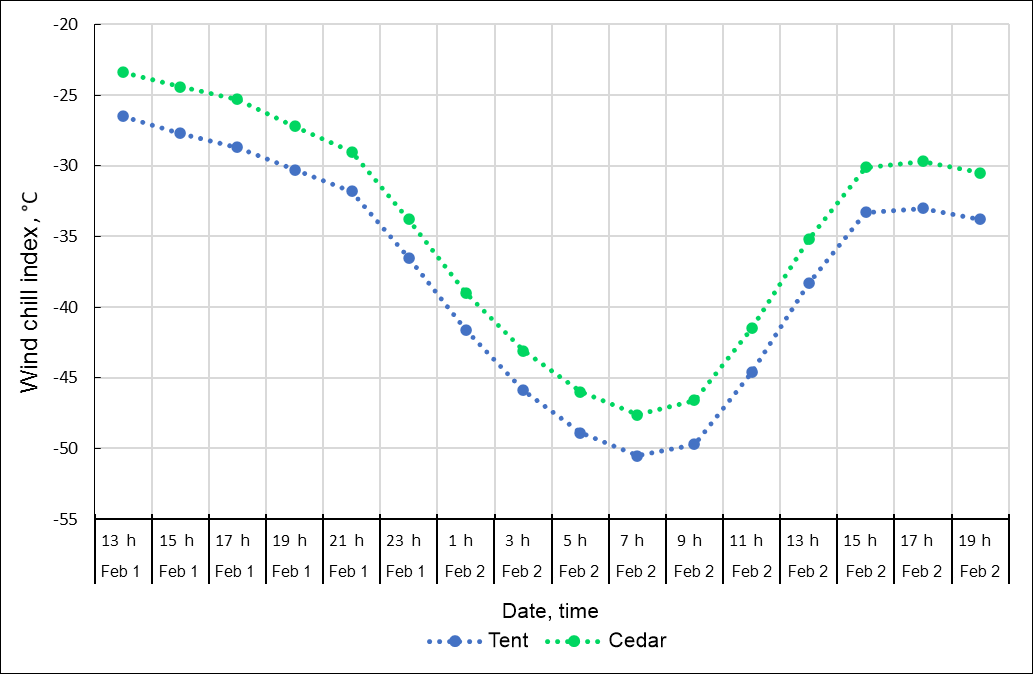

For the area under consideration, the wind-chill index was calculated based on the above-obtained values of temperature (Table 1) and wind speed (Table 2) for the locations of the tent and cedar. The calculations were performed using the formula given in GOST R ISO 15743-2012. Fig. 4 shows a graph of the wind-chill index change on February 1 and 2, 1959, at the "tent" and "cedar" sites. The distribution of the wind-chill index corresponds to the complex effect of temperature and wind, i.e. the lowest index values are typical for time intervals when high wind speeds and low temperatures were observed. Accordingly, the harshest conditions were at the location of the tent. Even at 19:00 on 1 February (at the time the hikers were camping), the weather conditions were similar to those of minus 30 degrees Celsius (the index was -30.3°C). The minimum index value (-50.5°C) was recorded here at 7:00 a.m. on 2 February. Slightly less severe conditions were at the location of the cedar: here the index was -27.2°C at 19:00, and -47.6°C at 7:00 am.

Fig. 4. Change in wind-chill index on February 1 and 2, 1959 at the locations of the tent and cedar.

Table 3 shows the wind-chill index values for the sites under consideration and the corresponding weather severity characteristic. As follows from the table, at the site of the tent, as early as 17:00 on February 1, weather conditions caused an average risk of hypothermia and frostbite, and as of 21:00, such conditions were also observed in the cedar area.

From 2 am in the cedar area, the weather conditions corresponded to a high risk of hypothermia and frostbite. At the tent level from 5 am to 9 am on February 2, there was a very high risk of hypothermia and frostbite (Table 3). Below is a description of the severity of the weather according to the wind-chill index and preventive measures against exposure to cold (required personal protective equipment) for the wind-chill index gradations highlighted in Table 3.

- Wind-chill index from -10 to -28. Discomfort, risk of hypothermia in case of prolonged exposure to the air without appropriate protection. It is recommended to dress in several layers of warm clothing, the outer layer should not let the wind through. It is recommended to wear a hat, mittens or gloves, a scarf and closed waterproof shoes. Stay dry and move in the cold.

- Wind chill index from -28 to -40. Exposed skin can freeze within 10-30 minutes. There is a risk of frostbite: it is necessary to check the face, exposed skin and extremities for rigor and blanching. Risk of hypothermia in case of prolonged exposure to the air without appropriate clothing or shelter from the cold and wind. It is recommended to dress in several layers of warm clothing, the outer layer should not let the wind through. It is recommended not to leave exposed areas of skin. It is recommended to wear a hat, mittens or gloves, a scarf, a mask and closed waterproof shoes. Stay dry and move in the cold.

- Wind chill index from -40 to -47. Exposed skin can freeze within 5-10 minutes. High risk of frostbite: Check face, exposed skin, and extremities for rigor mortis and whitening. Risk of hypothermia if exposed to air for prolonged periods without adequate clothing or shelter from the cold and wind. Dress in layers of warm clothing, with the outer layer being windproof. Avoid leaving exposed skin. Wear a hat, mittens or gloves, scarf, mask, and closed waterproof shoes. Stay dry and move around in cold weather.

- Wind chill index from -48 to -55. Exposed skin can freeze within 2-5 minutes. Very high risk of frostbite: Check face, exposed skin, and extremities for rigor mortis and whitening. Serious risk of hypothermia if exposed to air for prolonged periods without adequate clothing or shelter from the cold and wind. Exercise caution when outdoors. It is recommended to dress in several layers of warm clothing, the outer layer should not let the wind through. It is recommended not to leave exposed areas of skin. It is recommended to wear a hat, mittens or gloves, a scarf, a mask and closed waterproof shoes. Cancel or reduce trips outside. You need to stay dry and move.

- 6 -

Table 3

Table 3. Wind chill index values (°C) on February 1 and 2, 1959 at different times of the day in different locations in the Kholat Syakhl area

| Location | Altitude above sea level | Feb 1, 1959 | |||||

| 13 h | 15 h | 17 h | 19 h | 21 h | 23 h | ||

| tent | 890 | –26,5 | –27,7 | –28,7 | –30,3 | –31,8 | –36,5 |

| cedar | 633 | –23,4 | –24,4 | –25,3 | –27,2 | –29,0 | –33,8 |

| Feb 2, 1959 | |||||||||

| 1 h | 3 h | 5 h | 7 h | 9 h | 11 h | 13 h | 15 h | 17 h | 19 h |

| –41,6 | –45,9 | –48,9 | –50,5 | –49,7 | –44,6 | –38,3 | –33,3 | –33,0 | –33,8 |

| –39,0 | –43,1 | –46,0 | –47,6 | –46,6 | –41,5 | –35,2 | –30,1 | –29,7 | –30,5 |

Health hazard according to the chilling index

| Index values, °С | The degree of danger to human health | |

| from | to | |

| –10 | –28 | Low risk of hypothermia and frostbite |

| –28 | –40 | Average risk of hypothermia and frostbite of exposed skin within 10-30 minutes |

| –40 | –48 | High risk of hypothermia and frostbite of exposed skin within 5-10 minutes |

| –48 | –55 | Very high risk of hypothermia and frostbite of exposed skin within 2-5 minutes |

Based on the analysis of the obtained values of the wind-chill index and the list of the corresponding necessary personal protective equipment from the effects of cold, it can be concluded that in the clothes in which the hikers jumped out of the tent and went down the slope, they had no chance of surviving and returning to the tent even in the absence of physical injuries, since at the time when the hikers left the tent (at about 21:00), the wind-chill index both at the tent level (‒31.8°C) and at the cedar level (‒29.0°C) corresponded to an average risk of hypothermia and frostbite of exposed skin within 10-30 minutes. By the time the three hikers climbed the slope (around 3–5 am), the wind-chill index at the cedar level was already -43…-46°C, which corresponds to a high risk of hypothermia and frostbite of exposed skin within 5–10 minutes.

3.4. Precipitation and snow cover

Brief climatic characteristics. The amount and distribution of precipitation in the Northern Urals is determined mainly by cyclonic activity and relief features. The meridional orientation of the Ural Mountains causes an increase in precipitation on the western windward slopes and a decrease on the eastern leeward slopes (the "shadow" of the Urals). As a result, the total annual precipitation in the Cis-Urals is 150-200 mm higher than in the Trans-Urals. The same pattern in precipitation distribution applies to snow cover. The influence of the Ural Mountains is reflected in a decrease in the depth of snow cover on the eastern slopes of the Urals (Trans-Urals) by 20-30 cm compared to its height at the same latitude on the western slopes (Sub-Urals). Snow cover increases noticeably only at the beginning of winter (November-December), and later (in January and February) the depth of snow cover hardly changes, which is partly explained by strong compaction of snow under the influence of wind. Compaction is also caused by winter thaws, as a result of which ice crusts appear, which are then again covered with freshly fallen snow. Several such crusts may form during the winter.

Microclimatic characteristics. In mountainous areas, the distribution of winter precipitation is extremely varied. The nature of the relief, as well as frequent and strong winds, cause uneven snow cover. On mountain slopes and plateaus, under the influence of the wind, snow is redistributed, due to which windward slopes are bare of snow, and on leeward slopes and in places protected from the wind, a large amount of it accumulates. Snowdrifts on leeward slopes and in valleys can reach a height of 2-3 m or more, while on high-mountain plateaus there may be almost no snow. Winds with a force of more than 10 m/s, and especially more than 15 m/s, can completely remove snow from elevated areas, and the frequency of such winds in the area under consideration, as indicated above, is very significant.

It should be noted that due to the redistribution of snow under the influence of wind and relief features, winter precipitation in mountainous areas is difficult to account for, therefore, for the mountainous area under consideration, very high accuracy in calculating the spatial distribution of snow depth cannot be guaranteed without microclimatic observations, especially at such high wind speeds that prevail in the Urals.

For the territory under consideration, the snow depth at different points was calculated using known patterns of the influence of various relief forms on the redistribution of snow cover and taking into account snow transport factors (Pigol'tsina, Zinovieva, 2013, 2015). The initial information was obtained from observations of snow cover height for 19 hours on 1 February at the above-mentioned stations.

- 7 -

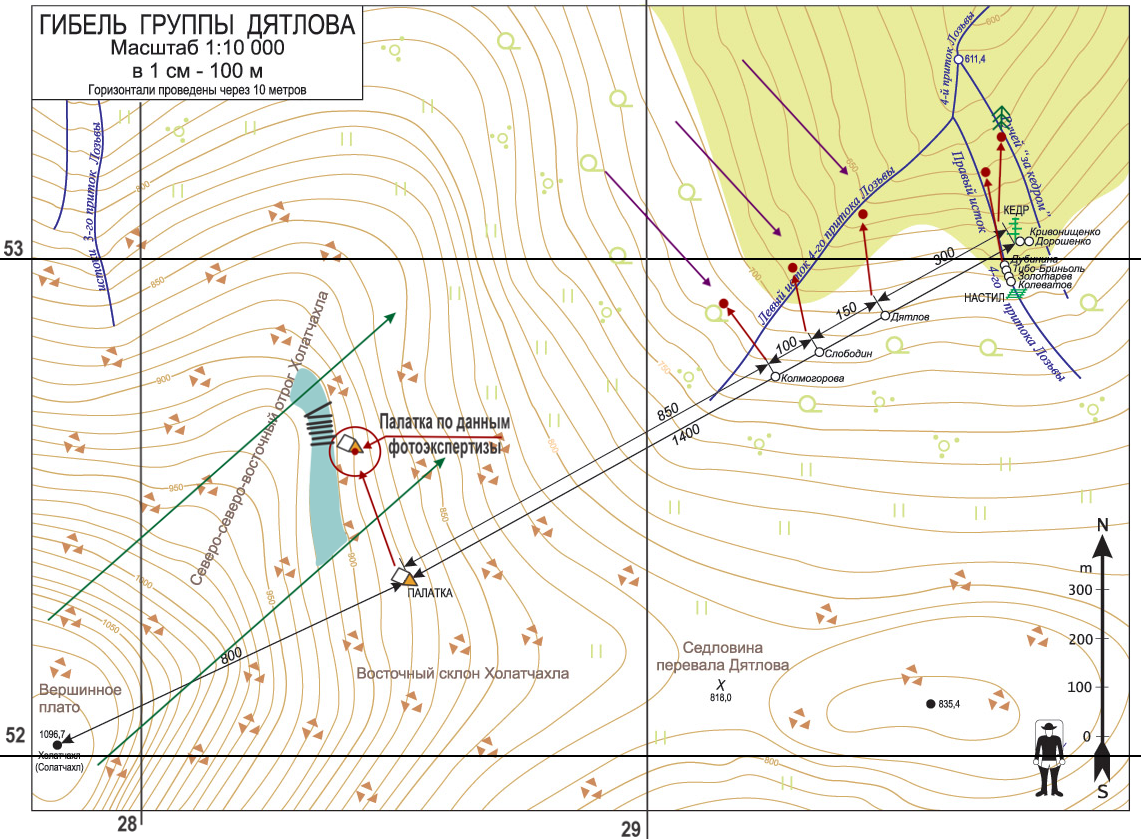

Fig. 5. Map-scheme of the slope of Mount Kholat Syakhl.

The area of maximum snow accumulation is highlighted in blue. The section with the maximum slope steepness is shown by hatching.

The green lines show the SW wind direction, the lilac lines - the NW direction.

With a SW wind blowing from the summit plateau of Mount Kholat Syakhl, on its leeward north-eastern slope, the zone of maximum snow accumulation will be located lower down the slope, while the difference in absolute heights of the plateau and the zone of maximum snow height, according to known patterns, should be 180-200 m. Thus, the zone of maximum snow accumulation is located between the isohypses of 920 and 900 m above sea level. In Fig. 5 shows a map-diagram, on which this zone is colored blue.

According to average long-term data, as indicated above, the frequency of southwest winds in the winter months is 21-22%. In January 1959, the frequency of southwest winds was 19%, i.e. close to the average values.

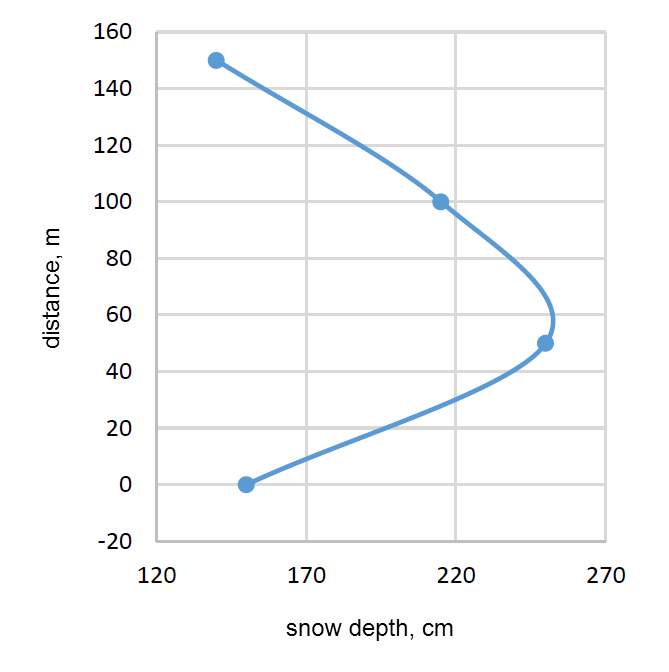

With a westerly wind, some of the snow blown off from the north-northeast (NNE) spur of Mount Kholat Syakhl will be added to this mass of snow, as a result of which a wider zone with a large height of snow cover will form in the northern part of the selected area, located closest to the top of the spur (i.e. to the north of the tent). The 900 m isohypse runs approximately 50 m above the tent. The distance from the tent to the top of the spur is approximately 150 m. Fig. 6 shows a graph of the change in snow depth at a distance from the tent to the top of the spur. The starting point is the tent (distance 0), the end point is the top of the spur (distance 150 m). The corresponding quantitative values of the snow depth are given in Table 4.

Thus, the zone of maximum snow accumulation is located above the tent, at a distance of approximately 50 m from it. In addition, the section of this zone adjacent directly to the tent on the north-west side, i.e. on the side opposite the entrance, has a steepness of 25-26°. This is the steepest section on this slope. It is shaded on the map (Fig. 5). The section on the northern side of the tent has a steepness of 21-22°. The steepness of the slopes was determined from a hypsometric map of scale 1:10,000 using a foundation chart.

- 8 -

Fig. 6. Change in snow depth at a distance from the tent to the summit of the NNW spur of Mount Kholat Syakhl.

Table 4

Change in snow depth at a distance from the tent to the summit of the NNW spur of Mount Kholat Syakhl

| Distance from the tent, m | Snow depth, cm |

| 0 | 150 |

| 50 | 250 |

| 100 | 215 |

| 150 | 140 |

With such steep slopes, a large snow mass and a layer of freshly fallen blizzard snow (more than 10 mm of precipitation fell in the mountains in two days), this area can be considered avalanche-prone. In addition, there was a strong wind, which, when a front passes, is usually accompanied by gusts of great force (30-35 m/s and more) (Orlova, 1962; Methodical recommendations ..., 1973; Scientific and applied handbook ..., 1990). Moreover, the wind was from the NW direction, i.e. it blew from top to bottom along the slope, albeit at an angle. From the above it follows that it was in this place, in the immediate vicinity of the tent on the side opposite the entrance, that an avalanche (one of the types of avalanches) could have occurred. This conclusion is fully consistent with the results of the assessment of the avalanche danger of this area, obtained by the expert glaciologist Victor Popovnin and provided to me for review by the Prosecutor's Office of the Sverdlovsk Region.

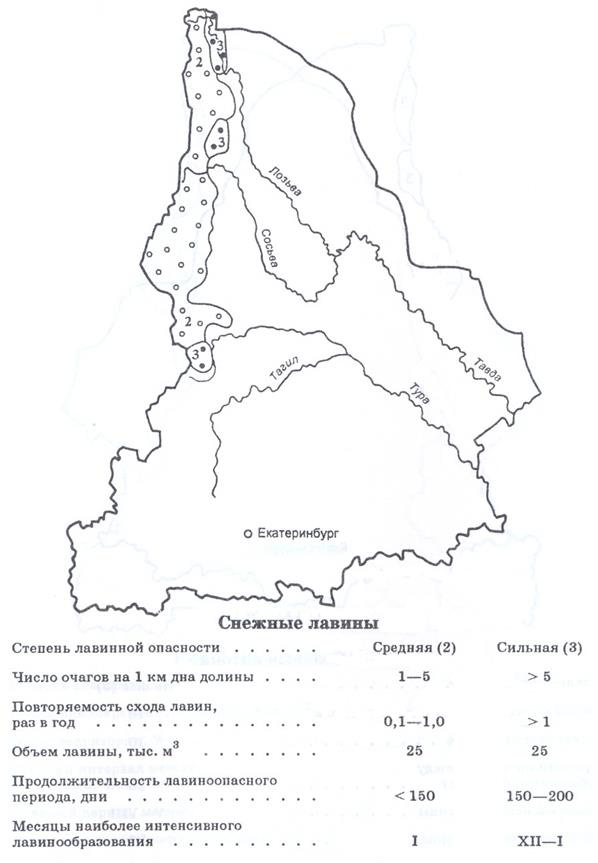

In general, the Dyatlov Pass area is avalanche-prone. In the "Handbook of dangerous natural phenomena in the republics, territories and regions of the Russian Federation" (1997), it is included in the zone with a medium degree of avalanche danger (zone 2). Fig. 7 from this handbook shows a map of the avalanche danger of the Sverdlovsk Region with a table of avalanche characteristic values. In this handbook, two parameters are used to assess the degree of avalanche danger: the number of avalanche centers per 1 km of the valley bottom and the frequency of avalanches - the number of avalanches that have occurred per year from one avalanche center. The combination of various gradations of these avalanche parameters allows us to distinguish three degrees of avalanche danger: 1 - weak, 2 - medium, 3 - strong.

The high snow cover in the lagoon (in the cedar area) is formed both by precipitation and by snow drift from all the hills bordering the valley in a horseshoe-shaped arc (on three sides). In the area under consideration, the volume of snow transported during the winter is 600-1000 m3/running meter (Mihel, Rudneva, 1967). With such snow transport, local depressions in the relief are completely covered with snow.

- 9 -

Fig. 7. Zoning of the Sverdlovsk Region by Avalanche Hazard (Handbook…, 1997).

4. Calculating Visibility on the Night of February 1-2

Astronomical Characteristics. On February 1, 1959, at the latitude of Dyatlov Pass, sunset was at 17:03 local time. Then comes twilight. Twilight is the time interval during which the Sun is below the horizon, and natural illumination on Earth is provided by the reflection of sunlight from the upper layers of the atmosphere and the residual luminescent glow of the atmosphere itself, caused by ionizing radiation from the Sun. Depending on the angle of the Sun below the horizon, twilight is divided into civil, navigational and astronomical.

Civil twilight corresponds to the depth of the Sun's immersion from 0 to 6 or 7°. At this time, twilight illumination is so intense that the visibility conditions of both distant and close objects are practically no different from daytime. During this twilight, one can easily do without artificial lighting. With the Sun's immersion at 6°, civil twilight on February 1 lasted 51 minutes in the study area, i.e. until 17:54.

It should be noted that in the place where the tent was set up, the mountains block the sunset, but the sky (high layers of the atmosphere) is illuminated, and the snow, reflecting this light, increases the level of natural illumination. The reflectivity (albedo) of pure snow is very high and amounts to 90 %. Thus, the loss of illumination due to the closed horizon was more than compensated for by the influence of snow cover. It follows that the last photographs of the hikers could well have been taken around 17 h without artificial lighting.

Navigational twilight corresponds to the depth of the Sun's immersion below the horizon from 6 to 12°. During this twilight, visibility rapidly deteriorates, forcing the use of lighting. In our case, navigational twilight lasted 1 hour 45 minutes and ended at 18 hours 45 minutes.

Astronomical twilight corresponds to the depth of the Sun's immersion from 12 to 18°. At this time, it becomes completely dark near the ground, but the sky in the dawn segment still retains a slightly increased brightness. Astronomical twilight lasted 2 hours 37 minutes and ended at 19 hours 40 minutes.

Next, when the Sun is below the horizon deeper than 18°, the sun's rays no longer reach even the uppermost layers of the atmosphere, the illumination does not change with the further immersion of the Sun, and night falls. On lunar nights, the illumination by moonlight depends on many astronomical factors, including the phase of the Moon, which causes a change in the area and average brightness of the bright part of the lunar disk. On the night of February 1-2, 1959, the Moon rose only at 4:14 am, so the night was moonless, and this simplifies the calculation of visibility. On the date of Feb 2, 1959, the Moon was in the "Waning Moon" phase, the disk fullness was 32% (waning crescent).

Visibility range, basic concepts. At the network of meteorological stations, meteorological visibility range (MVR) is determined using devices based on the use of various light sources. In the absence of devices, MVR is determined visually using a special technique. During daylight hours, this is the greatest distance from which a black object of sufficiently large angular dimensions (more than 15 arc minutes) can be distinguished (detected) against the sky near the horizon (or against the background of air haze). At night, this is the distance at which, given the existing air transparency, such an object could be detected if it were day instead of night. The MDV is observed instrumentally or visually using pre-selected objects. The concept of the visibility range of real objects is entirely based on determining the threshold of contrast sensitivity of vision.

- 10 -

The theory of visibility range of real objects has been developed quite fully. Visibility (but not visibility range) of any object is determined by the degree of difference in brightness (contrast) between this object and the background. Contrast in good visibility has a value of about 100 %. Visibility range of an object depends on the threshold of contrast sensitivity of vision (ɛ). The threshold of contrast sensitivity of vision is taken to be the minimum, barely perceptible by the eye difference in brightness between the object and the background. Based on theoretical and experimental studies carried out at the MGO, it was established that for daylight hours the value of the threshold of contrast sensitivity, lying in the middle between distinguishable and indistinguishable contrasts, has a value of 2%. This average two percent threshold is accepted in the extensive literature on visibility as the "classical" value of ɛ.

From the moment the Sun begins to sink below the horizon and the illumination level drops, the visibility of landscape objects gradually deteriorates. In the dead of night in moonless cloudy weather, the range of visibility of objects is literally measured in a few steps. The low range of visibility of objects at night is explained by a change in the properties of vision. This change consists in the fact that with a decrease in the illumination level, the threshold of contrast sensitivity of the eye (ɛ) increases. The value of ɛ, instead of a two percent value during the day, can have values in the range from 25 to 100% at night. Thus, due to the increase in the threshold of contrast sensitivity of the eye, the visibility of objects at night is lost at much closer distances than during the day. But in addition to the increase in the value of ɛ, visual acuity also drops sharply at night. These are the peculiarities of perceiving real objects at night.

On lunar nights, at different phases of the moon, the comparatively low values of visibility range are also explained not by a decrease in the contrast between the object and the background, but only by an increase in the threshold of contrast sensitivity of the eye and a drop in visual acuity. On lunar nights, one can see further than on moonless nights, because due to the higher level of illumination, the contrast sensitivity of the eye increases somewhat, and visual acuity also increases. But even with a full moon, the threshold value ɛ can never reach the value of 2 %, corresponding to daytime observation. On average, the visibility range of objects on lunar nights occupies an intermediate value between daytime and nighttime values.

The visibility range of real objects depends not only on the value of their own brightness (contrast with the background), but also on their angular dimensions, recorded from the observation point. If you move away from an object of any size to such a distance that its angular dimensions become less than the visual acuity threshold, i.e. the object will be visible at an angle of less than 1 sq. minute, then it will not be visible at all, even if its contrast with the background is 100%. In addition, the visibility range of objects depends on specific observation conditions and, first of all, on meteorological factors.

Calculating visibility range on the night of February 1-2. The visibility range of a small-sized real object (including a tent) is determined by the distance at which its observed angular dimensions become equal to the visual acuity threshold. The critical distance for perceiving small-sized objects is 1 km with an angular size of an object of 225 sq. minutes, which corresponds to an object size of 4 × 4 m (the side of a square is 15ʹ).

Thus, with a tent size of 1.5 × 4.3 m, its angular dimensions will be 90.7 sq. minutes. Accordingly, the visibility range will be equal to 403 m. From such a distance, you can distinguish a tent in the daytime with good visibility.

It is known that contrast does not change with changes in illumination. But although an object will have 100% contrast both during the day and at night, its actual visibility at night will be very poor, since vision properties change at low illumination (as discussed above). So, if during the day, with the value of the threshold of contrast sensitivity of the eye ɛ equal to 2 %, the visibility coefficient of an object will be equal to 100 : 2 = 50, then at night, with a threshold value of 25 % (i.e. with minimal influence of night), the visibility coefficient of an object will already be equal to 100 : 25 = 4. Thus, the same object will be 12.5 times less visible at night than during the day (50 : 4 = 12.5). This means that the above-defined value of visibility for daylight hours, equal to 403 m, will be only 32m at night (403:12.5=32).

Snowfall and snowstorms reduce visibility. Even light snowfall (0.1-0.5 mm/h) reduces visibility by 50-80%. In principle, the effect of snowfall can be identified with the effect of a snowstorm. While the hikers were both in the tent and in the cedar area, it was snowing. Even if we assume that the snowfall was interrupted, then under the influence of a strong wind, which was observed all this time, the freshly fallen snow was subject to intensive transfer, i.e. there was a blizzard. Thus, under the influence of a snowfall (blizzard), the visibility range calculated above (32 m) can fluctuate within the range of 6 to 16 m. It follows that even with a minimal influence of all the factors considered on the visibility range on the night of February 1-2 (including at 9 p.m., when the hikers presumably urgently began to descend the slope), the tent could be distinguished from a distance of no more than 16 m. In this case, we can say with 100% certainty that the hikers, having moved 30-50 m away from the tent, could not see it.

- 11 -

5. Comments on the choice of the route for the ascent of three hikers to the tent

The valley of the left source of the fourth tributary of the Lozva, along the bottom of which the three hikers began to ascend, is directed from the southwest to the northeast. The wind on February 1st and 2nd was from the northwest, i.e. it blew perpendicular to the valley (Fig. 5, lilac lines). Consequently, with such a wind direction, the bottom of the valley had a "wind" (orographic) shadow, at least in the lower part of the valley, from where the hikers began to ascend. The lower part of the valley, judging by the hypsometric map, has a more pronounced dissection, and here at the bottom of the valley the wind speed was 2-3 m less than near the cedar. This difference is caused by the fact that the cedar is located on relatively flat terrain without orographic shadow.

Reduced wind speed is a big advantage when climbing a slope, most likely it was this factor that influenced the choice of route. As they moved up the valley, the depth of the valley decreased, and the hikers' route deviated slightly to the north. The wind speed increased accordingly, and at the altitude where Kolmogorova and Slobodin were found, the wind speed was almost no different from the speed in the open.

The valley had fairly deep snow with a freshly fallen top layer, which was difficult to walk on, in addition, a strong wind was blowing. Under such conditions, frozen, frostbitten and tired people most likely did not walk, but crawled on the snow. As a result, after Kolmogorova, who was the first to climb, there should have been a "track" left, along which the other two hikers followed. This can explain the movement of all three hikers along one line (Fig. 5).

Conclusions

A detailed microclimatic assessment of the area showed that with the northwest wind direction observed on February 1 and 2, 1959, the wind shadow zone was only on the leeward side of the north-northeast spur of Mount Kholat Syakhl, where the tent was located. Moreover, the tent was pitched in the immediate vicinity of the zone of maximum snow accumulation below a powerful snowdrift, which increased the effect of its protection from the wind. Thus, the hikers stopped and pitched the tent in the wind shadow, with a relative decrease in the power of the wind flow in this place of the slope by 10-15% relative to the surrounding area.

Based on the analysis of the obtained wind-chill index values and the list of the corresponding necessary personal protective equipment against exposure to cold, it can be concluded that in the clothes in which the hikers jumped out of the tent and went down the slope, they had no chance of surviving and returning to the tent even in the absence of physical injuries. At the time when the hikers left the tent (at about 9 p.m.), the wind-chill index both at the tent level (‒31.8°C) and at the cedar level (‒29.0°C) corresponded to an average risk of hypothermia and frostbite of exposed skin within 10-30 minutes. By the time the three hikers climbed the slope (around 3-5 a.m.), the wind-chill index at the cedar level was already -43…-46 °C, which corresponds to a high risk of hypothermia and frostbite of exposed skin within 5-10 minutes. These weather conditions, when outdoors without appropriate clothing, can quickly lead to hypothermia and, ultimately, death.

A quantitative assessment of the spatial distribution of snow depth and an analysis of a large-scale hypsometric map made it possible to identify an area on the slope of Mount Kholat Syakhl with maximum snow accumulation (snow depth of about 250 cm) and a steep slope (25-26°), representing a potential avalanche hazard zone located in the immediate vicinity of the tent. An analysis of weather conditions showed that on the evening of February 1 (at 8-9 pm) a cold front passed over the area, which caused a sharp drop in air temperature towards colder temperatures and increased wind, accompanied by snowfall and blizzards, that is, meteorological conditions contributed to the occurrence of avalanche activity. Thus, there were all the prerequisites for an avalanche (one of the types of avalanches), and it can be concluded that an avalanche could have occurred with a high degree of probability, especially since this area is characterized by an average degree of avalanche danger.

Calculation of the actual visibility range at night, taking into account astronomical and meteorological factors, showed that even with the minimal influence of these factors on the visibility range on the night of February 1-2 (including at 9 p.m., when the hikers presumably urgently began to descend the slope), the tent could be seen from a distance of no more than 16 m. In this case, it can be stated with 100% certainty that the hikers, having moved 30-50 m away from the tent, could not see it.

The high snow cover in the cedar area was formed both due to precipitation and due to snow drift from all the heights, bordering the valley in a horseshoe-shaped arc. In the region under consideration, the volume of snow transported during the winter is 600-1000 m3/running meter. With such transport, local depressions in the relief are completely covered with snow.

References

Methodological recommendations of the Sverdlovsk Weather Bureau (1973). Vol. 5.

Microclimate of the USSR (1967) / Ed. I.A. Goltsberg. - L.: Gidrometeoizdat. 284 pp.

Mihel V.M., Rudneva A.V. (1967). Zoning of the territory of the USSR according to snow transfer // Proceedings of the GGO. Vol. 210. P. 79-91.

Scientific and Applied Handbook on the Climate of the USSR (1990). Series 3. Long-term Data. Parts 1-6. Issue 9. - L.: Gidrometeoizdat.

Orlova V.V. (1962). Climate of the USSR. Western Siberia. Issue 4. - L.: Gidrometeoizdat. 360 pp.

Pigol'tsina G.B., Zinovieva N.A. (2009). Methods for assessing microclimatic variability of specialized climatic characteristics in mountainous terrain and insufficient meteorological information using the example of the territory where the Sochi 2014 Winter Olympic Games will be held // In the collection: Proceedings of the All-Russian conference dedicated to the 100th anniversary of Professor Oleg Alekseevich Drozdov. St. Petersburg. October 20-22, 2009. - P. 124-126.

Pigoltsina G.B., Zinovieva N.A. (2013). Spatial distribution of snow depth in the mountain cluster of the territory of the Sochi 2014 Winter Olympic Games // Proceedings of the Main Geographical Society. Issue. 569. P. 137-147.

Pigoltsina G.B., Zinovieva N.A. (2014). Patterns of Wind Speed Change with Height on the Leeward Slope of a Mountain Range (using the Northern Slope of the Aibga Ridge as an Example) // Proceedings of the Main Geographical Survey. Issue 575. pp. 119-130.

Pigol'tsina G.B., Zinovieva N.A. (2015). Assessment of Microclimatic Conditions of the Mountain Cluster of the Krasnaya Polyana Region to Provide Sports Facilities with Detailed Weather and Climate Information // Meteorology and Hydrology. №8. pp. 88-97.

Handbook of Natural Hazards in the Republics, Territories, and Regions of the Russian Federation (1997). — SPb: Gidrometeoizdat. 588 s