MOSCOW Leninskie Gory, Moscow, GSP-2, 119992 May 14, 2019__№________ | To the Prosecutor's Office of the Sverdlovsk Region |

Answer

expert glaciologist VICTOR POPOVNIN to questions

Prosecutor's Office of the Sverdlovsk Region for Dyatlov Pass

Answers to questions posed in the initial letter dated 18.03.2019

1. What is an avalanche?

A snow avalanche is the movement of snow masses down a slope under the action of gravity [Tushinsky G.K. Avalanches. Origin and Protection from Them. Moscow, Geografgiz, 1949; Glaciological Dictionary (ed. by V.M. Kotlyakov). Leningrad, Gidrometeoizdat, 1984]. It can occur in the form of sliding or saltation (i.e. the overthrow of snow masses in jumps, with separation from the surface). In a strict scientific sense, neither the volume of snow involved in the movement, nor the distance of the ejection are of great importance to be called an avalanche - the range of values of these parameters is very large. Both small blocks of snow set in motion and snow masses of millions of cubic meters can equally be classified as avalanches. The throwing distance also varies from the very first tens of meters to many kilometers (there are known facts of snow material moving in our country up to 6.5 km, and in South America - up to 16 km). The diversity of avalanches occurring in nature is expressed in differences in the causes of occurrence, the zone of origin (from a point or front), the transit route (flat slope, trough, steep cliffs ...), the type of snow (freshly fallen, blizzard ...), its humidity, the nature of movement and many other indicators. As a rule, snow avalanches originate on slopes with a steepness of more than 15 °, although exceptions are known with minimal angles of inclination of even 12 °. Most often, snow avalanches are recorded on slopes with a steepness of 25 = 35 °.

2. What is a "snow slab"?

A snow (or wind) slab is a surface layer of snow with a density over 0.40 g/cm3, or 400 kg/m3, consisting of crystals tightly packed by the wind and possessing increased adhesion compared to loose snow [K.F. Voitkovsky. Fundamentals of Glaciology. Moscow, Nauka Publishing House, 1999]. It usually forms during very strong winds, more often on windward slopes. On leeward slopes, a snow slab is held on the slope only due to its internal strength and insignificant adhesion to the underlying surface. The thickness of such a layer can reach several decimeters, in which case it is called a snow slab. A characteristic feature of the collapse of snow slabs is the simultaneous disruption of the stability of the snow cover over a significant area, which is accompanied by a rupture of the layer at the upper boundary of this area. The visible boundary of the separation is a broken line or an uneven arc at the top of the avalanche basin. The surface of the separation is close to a plane perpendicular to the base of the snow slab.

3. What is the difference between an avalanche and a "snow slab", including the mechanism of formation?

The question is not quite correctly formulated. An avalanche is a phenomenon, a process. A snow slab is a motionless upper layer of snow. Another thing is that when certain conditions are created, this layer begins to move, and then so-called avalanches from a snow slab occur. Therefore, it is more correct to contrast avalanches from a snow slab (but not the snow slab itself!) with all other types of avalanches - for example, from freshly fallen snow, loose from a point, etc. The mechanism of the initial shift of the snow mass in the case of a snow slab differs from these other cases. Under a snow slab, as a result of physical processes of snow recrystallization, loosened horizons with voids often arise, which leads to the subsidence of its individual sharp-edged blocks, a violation of the continuity equation and the beginning of the movement of snow masses. This subsidence can occur after a long period of time, necessary for recrystallization (i.e., a change in the size and shape of snow grains) to lead to the creation of critical values of adhesion to the underlying snow layers, but it can also occur earlier in the case of external influence (including anthropogenic). Other types of avalanches (not from snow slabs) can occur only a short time after excess snow masses have been deposited on the slope (the case of avalanches from fresh snow after heavy snowfalls), or they can - similar to avalanches from snow slabs - wait until stratigraphic conditions within the snow cover mature, allowing one layer to slide over another.

4. What weather conditions (air temperature and humidity, wind force, snow cover thickness, etc.) contribute to the formation of an avalanche?

The conditions for an avalanche are created not only by quantitative values of meteorological indicators, but, what is much more important, by the rate of their changes (time gradient). At the same time, almost all of the listed meteorological elements influence the occurrence of avalanches.

- 2 -

However, the role of each varies greatly, and in different situations the same meteorological element can lead to both an increase and a decrease in the degree of avalanche danger. Therefore, it is impossible to give a clear and simple answer to this question. The influence of air temperature is most diverse. When it increases, there is a risk of wet avalanches, when it decreases, avalanches of temperature compression begin to descend. Air temperature predetermines the thermal properties inside the snow cover - first of all, the distribution of snow temperature by depth and the variation of the temperature gradient. The complexity of the vertical temperature diagram inside the thickness leads to the recrystallization of snow at different depths at different speeds. It is this process that creates stratigraphic heterogeneity of the snow layer - and this is one of the main (if not the most important) reasons for the loss of stability of the layer on the slope. Air humidity determines the gradients of partial pressure of water vapor, which also control the process of recrystallization inside the snow cover and increase its stratigraphic heterogeneity. Sublimation in heated horizons causes loosening of snow and redistribution of matter: in warmer horizons, due to diffusion, there is a loss of matter and a decrease in density, in colder horizons, sublimation and an increase in density prevail. The higher the gradient of water vapor pressure, the more matter will move from one layer to another due to diffusion and the sooner a dangerous layer of loosening up to deep hoarfrost will appear in the warm horizon - a stratigraphic element that most often provokes a shift in the snow layer and generates an avalanche [A.I. Popov, G.K. Tushinsky. Permafrost Science and Glaciology. Moscow, "Higher School", 1973]. On the one hand, wind force leads to deflation - snowstorm redistribution of deposited snow and creation of centers of increased snow accumulation, and on the other hand, it serves as the main factor in the formation of a layer of surface compaction - crust, snow slab. The intensity and duration of each individual snowfall creates its own conditions for avalanches: the faster new portions of snow accumulate on the slope, the faster the avalanche threat increases. The rate of accumulation and the mass of newly accumulated snow create their own stratigraphic contrasts, namely, they contain a kind of "trigger" mechanism for avalanche formation. The greater the thickness of the accumulated snow, the faster the conditions for setting it in motion will be created. This factor should be considered together with the relief factor - specifically, with its steepness, first of all. Thus, at a slope angle of 25°, only a 30-cm layer of snow is enough to cause an avalanche.

5. What forms of terrain contribute to the formation and descent of an avalanche?

Avalanches are facilitated by those forms of terrain that provide a slope steep enough to start the avalanche process (i.e. 15°, see point 1). Such slopes can be found in a wide variety of geomorphological settings - these are flat surfaces, steep-walled frames of deformed cirques and circuses, and erosion troughs, gullies and crevasses. As soon as the threshold value of the slope angle is exceeded, any relief form will become avalanche-prone - the types of avalanches will simply differ: thus, on flat slope surfaces, avalanches will originate, starting from the breakaway line and spreading further down in a wide front (the so-called troughs), while trough avalanches will be confined to the troughs extended down the slope. In order to assess the probability of an avalanche initiation, it is very important to trace the nature of the change in the slope angle along the longitudinal profile. Sections with a predominantly convex profile are more susceptible to the risk of avalanche formation than sections with a concave one. If there are steep steps in the longitudinal profile, jumping avalanches occur. Alternation of mesorelief forms along the longitudinal profile, measuring only a few meters, but differing in the angle of the surface slope, can cause a shift in the layer on a convex section even if the background morphometric characteristics of the entire slope as a whole do not seem to provide grounds for classifying it as avalanche-hazardous. Such a situation with the alternation of small rocky ridges, by the way, is very typical for the slope of Mount Kholat Syakhl. However, the same rocky ridges across the slope in winters with low snowfall can play the role of natural barrages, restraining the processes of formation of large avalanches and slowing down the snow layer that has begun to slide from areas higher up the slope.

- 3 -

6. What are the signs that an avalanche may start?

The question is not quite clearly formulated. What is "the start of an avalanche"? An avalanche is a relatively fast process, it can be considered instantaneous with a certain conventionality, so the "start" of this moment is a rather unclear phrase. Most likely, the authors of the question are interested in whether it is possible to predict an avalanche by any signs. If I understood the idea correctly, the answer is: no, it is not possible. An operational avalanche forecast (i.e. a prediction that an avalanche should be expected in a given place at a certain moment in time) is currently impossible, unrealistic. Theoretically, in some ideal research conditions (let's say, at an experimental site, where the test snow mass is stuffed with all sorts of equipment for continuous automated measurement of thermal and mechanical properties), this can still be allowed, and even then with a certain amount of imagination. Unfortunately, science cannot yet give an exact forecast of the moment of the snow layer shift. Usually, such a task is reduced only to declaring a certain degree of avalanche danger, but nothing more specific. At the same time, it is implied that it is possible to notify in advance that the snow on the slope is "ripe", and therefore any external impact (whether it is a skier cutting a snow slope, the load on the snow-covered surface from the appearance of a group of people on it, etc.) can provoke an avalanche - although without such an impact, the snow can continue to remain stable. An experienced specialist is able to issue such a warning in advance based on the results of an analysis of the synoptic situation of the previous period and based on his observations, measurements and sensations on a known safe (gentle) snow-covered slope-analogue at a distance. If a characteristic subsidence of the snow layer is felt on it from the load - say, a skier (as described above in point 3), then this will most likely mean that on a steeper slope such a load and the resulting subsidence will act as a trigger mechanism and cause an avalanche. But in any case, such a forecast will only have a probabilistic nature. In other words, a specialist can give a conclusion about the beginning of the avalanche-prone period, but not about the moment of the expected avalanche.

7. What traces on the terrain can indicate an avalanche?

If we are talking about the background picture (about those areas where avalanches have occurred before and continue to occur today), then such places are recognized in the landscape primarily by vegetation - by avalanche combs among the forest belt, by birch crooked forests, by deformed and broken tree trunks, etc. If we are talking about traces of a specific avalanche, then for some time after its descent, this event remains imprinted in the nature of snow deposits, and often as a consequence, by a specific positive form of mesorelief in the form of hummocks or ramparts due to the concentration of snow material transferred there. Snow deposits on alluvial fans depend on the type of avalanche. In the case of a trough avalanche or an avalanche from a point, lumpy-block snow material is deposited on the cones (especially in the case of wet avalanches). In the case of an avalanche (an avalanche of snow slabs), the layer that has slid down the slope may be split into separate prismatic blocks, which did not turn over during the avalanche, but slid down - in this case, the alluvial cone may be a multitude of fragments of the former compacted surface layer of snow, cut by cracks, the roof planes of which retain a relatively flat appearance. Another thing is that both lumpy-block and cracked prismatic deposits will lose their distinctiveness in the relief rather quickly, since they will be covered by an even layer of new fresh snow after the next snowfall: the cracks will be filled in, the unevenness between the lumps will be leveled. The fact that an avalanche has recently occurred here will be indicated only by the relative elevation of the daylight surface above the surrounding areas not affected by the processes of avalanche redistribution.

8. What weather conditions (air temperature and humidity, wind force, snow cover thickness, etc.) contribute to the formation of a "snow slab"?

In fact, the answers largely repeat the content of point 4, since an avalanche from a snow slab is only a separate special case of avalanches. The specificity of weather conditions for the formation of a slab comes down only to the special role of the wind regime, since it is the wind that is the main reason for the formation of a surface compaction layer. In addition to wind, a compacted layer at the surface of the snow cover can be created as a result of the formation of an ice crust (crust) due to episodic thaws with the dominance of stable warm weather without precipitation during the day and low temperatures at night.

- 4 -

9. What types of terrain contribute to the formation and avalanche of a "snow slab"?

First of all, the slope should be relatively weakly dissected and free of frequent and sharp bends. Everything else depends on the meteorological conditions (see item 8).

10. What signs indicate the possible onset of a "snow slab" avalanche?

In general, everything written in item 6 is true. The slab also has its own specific signs. Thus, a harbinger of the fact that a snow slab has formed on the slope, ready to lose stability, is the occasional subsidence, accompanied by a hum. The hum occurs due to the air being squeezed out of the slabs. If you step on a snow slab ready to slide, you can see cracks rapidly spreading in different directions and hear a dull rumble from the movement of the fragments of the slab. But just as in the general case, an operational forecast of an avalanche from a snow slab is unrealistic.

11. What traces on the ground can indicate an avalanche of a "snow slab"?

See item 7 in terms of deposits from pr,ismatic fragments of a snow slab. Sometimes a snow slab can literally slide down to the nearest flattening, traveling only a few meters, and stop there; in this case, the fragments will be separated by a network of very narrow cracks, which will be quickly covered by fresh snow during the next snowfall.

12. Is it possible for an avalanche or "snow slab" to form in the area where the group of hikers who died on Feb 2, 1959, in the area of Mount Otorten, Ivdel, Sverdlovsk Region, set up their tent, given the terrain? What are the signs?

The tent set up area is definitely in an avalanche-prone area. Both point avalanches and snow slab avalanches can form here (there are even more prerequisites for the latter). This is facilitated by: a) the steepness of the slope exceeding the critical value of 15° - the background slope angle as measured by an eclipter is 21°; b) the presence of minor transverse rocky ridges hidden under the seasonal snow, but nevertheless creating a step-like character of the longitudinal profile of the snow surface - in areas below the crests of these rocky ridges the steepness locally increases by several degrees, thereby increasing the probability of a shift of the snow layer from top to bottom along the edge at least to the lower located more gentle step (to which, incidentally, the place where the Dyatlov group pitched their tent was confined); c) the general weak dissection of the slope, contributing to the formation of avalanches with a frontal line of separation (washouts); d) the morphological openness of the terrain in relation to the prevailing winds, the absence of a wind shadow and, because of this, the predisposition of the slope to the formation of washouts on it. The rocky ridge hidden under the snow above the site where the tent was pitched could also play a certain role in the movement of a snow slab along the slope. Most likely, the avalanche originated higher up the slope. Its trajectory, usually aligned normal to the isohypses (isolines of equal absolute height), deviated orographically (i.e., if you look down the slope) to the left due to the approach to the snow-covered ridge of stones. Its lateral (right) periphery could have touched the orographically left part of the tent set up across the slope, which is why this part was covered with avalanche snow and masses, causing injuries to people lying on this edge of the tent, while the skis-stretchers in the right part of the tent remained standing, and the people lying there were not injured.

13. What weather conditions (air temperature and humidity, wind force, thickness of snow cover, etc.) could contribute to the formation of an avalanche or "snow slab" in the area where the tent of the group of hikers who died on Feb 2, 1959, in the area of Mount Otorten in the city of Ivdel in the Sverdlovsk region was set up?

According to the meteorological archive, that night, due to baric instability, the weather conditions sharply worsened and conditions developed that were favorable for the snow layer to fall off the slope: a) a sharp drop in air temperature towards -26°C, which contributes to the occurrence of temperature-decreasing avalanches, when frost cracking occurs in the snow layer, weakening the adhesion; b) intensive deflationary (blizzard) activity, which predetermines the accelerated accumulation of blown snow and increases the potential for avalanche danger; c) the concentration of considerable masses of snow at the site of the tent, confirmed by the fact that, according to the results of the snow survey I conducted at this site in March 2019, the thickness of the snow cover varied from 96 to 169 cm, and 20 m to the north it reached as much as 243 cm (it must be assumed that on the night of February 2, 1959, there was more snow than in the relatively low-snow spring of 2019); d) strong wind during the night itself and the preceding period of time, which caused compaction of the compacted snow near the surface and the formation of a typical snow slab; d) the thickness and density of the snow slab could reach values that were capable of having a traumatic effect on people, since even in the more gentle conditions of March 2019. the thickness of the board reached 26 cm, and its density was 0.39 g/cm3, meaning that the weight of 1 m3 of such compressed snow was 390 kg.

14. Is it possible for human footprints to form on the snow cover in the form of ice columns?

Yes, it is possible.

- 5 -

15. What weather conditions (air temperature and humidity, wind strength, snow thickness, etc.) can contribute to the formation of human footprints on the snow cover in the form of ice columns?

The formation of columns from human footprints is largely facilitated not even by weather conditions, but by the properties of the snow layer: it must be represented by loose snow, mainly of blizzard genesis. For snow to be such, the following synoptic conditions are required: low air and snow temperatures, low air humidity, strong wind, drifting snow. It is only necessary to immediately note in order to avoid any further incidents: the columns into which the footprints of the Dyatlov group members turned can hardly be called ice - it is clearly visible from the photographs that they are not made of ice, but of compressed and highly compacted snow (unfortunately, it is often necessary to deal with the fact that people who are far from glaciology and snow science cannot distinguish compacted snow from firn or ice). Such formations in glaciology are called sastrugi. Despite the fact that sastrugi are purely natural formations, they have many common features in the structure and structure of snow with the columns left by human footprints.

16. What is the mechanism of formation of human footprints on the snow cover in the form of ice columns?

Under the load that a person's foot exerts on loose snowdrifts, each step leaves a trace in the form of a hole, the depth of which depends on the weight of the person and the strength of the upper layer of snow cover. Snowdrifts do not support the foot, so the holes are deep. The base of the hole is made of artificially compacted snow (from the pressure exerted by the foot), while the walls of the hole are represented by the original loose snowdrifts. Subsequently, the hole can be covered with the same loose snow if the drifting snow continues, because any depression in the snow microrelief is a natural catcher for snow carried by the wind. But if the wind does not weaken further and continues to blow, deflation processes develop on the surface, i.e. blowing of snow and its removal by wind [Dyunin A.K. Mechanics of snowstorms. Novosibirsk, Publishing House of the Siberian Branch of the USSR Academy of Sciences, 1963]. The intensity of removal will be determined by the density of the snow mass: loose powdery snow will be the first to be subject to deflation, while compacted snow substance is more difficult to involve in movement. In such a situation, the structural differentiation of the snow around the hole will be of decisive importance: while the loose snow forming the walls and accumulated in the cavity of the hole will be gradually blown out by the incessant wind, the dense snow at the base of the hole will resist deflationary removal. As a result, after the surrounding loose snow has been blown out by the wind, the compacted snow from the sole of the foot will remain in place and over time, with continued blowing of adjacent snow masses, will form low columns akin to sastrugi. It should be added that on an old snow trail, human footprints in the form of not depressions, but on the contrary, hillocks (mounds, columns) are not at all uncommon; they are very often found in the mountains, when subsequent groups of hikers or climbers prefer to move along a path checked for safety by the previous group.

17. What weather conditions and their period can be indicated by the footprints discovered by the search party in the area of the hikers' death on Feb 2, 1959, in the area of Mount Otorten, Ivdel, Sverdlovsk Region?

Presumably, Dyatlov's group descended from the cut tent along the snow-covered surface of the slope, which was a previously formed snow slab, in places (mostly) covered by a layer of fresh snow of variable thickness, and in places deprived of this layer. This explains the dotted pattern of the tracks left, as they were later discovered by the search party: where Dyatlov's group descended along the deposits of snow, they left tracks in the form of holes, and where they walked on a snow slab deprived of these deposits, the foot did not fall through and simply did not leave tracks. The good preservation of the tracks, noted by searchers many days after the night of the Dyatlov group's death, indicates that the weather conditions described above in paragraphs 13, 15, 16 (cold, wind) remained relatively unchanged for a long period of time after Feb 2, 1959.

- 6 -

Answers to questions posed in the additional letter dated 18.04.2019

1. Is an avalanche or snow slab possible on Mount Kholat Syakhl? If so, what is its location on the mountain slope (the entire slope, the upper, lower, central, right, left parts of the slope)?

As noted earlier in paragraph 12 of the first block of answers, various types of avalanches are possible on Mount Kholat Syakhl, including avalanches from a snow slab. The vast majority of the slope is avalanche-prone, with the exception of those sections where the steepness does not exceed the critical threshold of 15°: such gentle sections are noted near the watershed ridge and in the lower part of the slope, directly adjacent to the tree vegetation belt. Unfortunately, the scale of the map and the quality of the photograph do not allow us to outline the zones of potential avalanche danger, but this is not so important: in the middle-height part of the slope, avalanches are likely in all sectors.

2. When an avalanche or snow slab comes down, what physical phenomena occur simultaneously with it (before, after) - air shock, vibration, sound wave, etc.? At what distance are these physical phenomena recorded, what is their strength?

Different types of avalanches are accompanied by different physical phenomena, including those listed. An air wave is typical, first of all, of dust avalanches (of dry snow or firn, accompanied by a cloud of snow dust). It has the form of a snow-air flow/vortex rushing in front of the avalanche body with a breakaway from it - including after a complete stop. snow avalanche masses [Losev KS Avalanches of the USSR. L., Gidrometeoizdat, 1966]. The path of the air wave after breakaway can be up to 12-20% of the path of the main body of the avalanche. Sound, vibration and other vibrations can precede the avalanche; they occur in a complex-stressed state of the snow cover and have been studied comparatively poorly. I wrote about the rumble caused by the subsidence of snow slabs above (see item 10 from the first block of answers). The impact force of an avalanche can be reflected in seismograms, so we can also talk about seismic phenomena. When avalanches come down, an optical effect sometimes occurs - luminous discharges. The distances at which these physical phenomena can be recorded and registered can be very different and depend on the parameters of each specific avalanche. In general, little is known about the acoustic, optical and electromagnetic waves that accompany avalanches.

3. Which of these phenomena are possible on Mount Kholat Syakhl, taking into account the orography. If necessary, we will provide additional documents, information.

I find it difficult to answer. I do not think that, apart from a slight sound effect when coming down, avalanches on Mount Kholat Syakhl are capable of producing significant physical phenomena from among those listed.

Faculty of Geography, Lomonosov Moscow State University,

Ph.D. in Geogr.

/V.V.Popovnin/

May 14, 2019

- 7 -

Leninskie Gory, Moscow, GSP-2, 119992 Jul 30, 2019__№________ | To the Prosecutor's Office of the Sverdlovsk Region |

Answer

expert glaciologist VICTOR POPOVNIN to questions

Prosecutor's Office of the Sverdlovsk Region for Dyatlov Pass

Responses to the request from Jul 27, 2019

Snow measurements at the site of the Dyatlov group's tent were carried out on March 18, 2019. The measurements were carried out using the direct area snow survey method.

Snow measurements are understood as determining the water equivalent E of the accumulated snow cover (usually in millimeters of water layer), which essentially means the thickness of the water layer that could have formed as a result of the melting of the measured snow layer. In glaciology (as in all other disciplines of the hydrometeorological profile), the parameter of snow accumulation (E) is calculated by the formula:

E = 10ρн,

where ρ (g/cm3) is the integral density of snow over the entire section of the snow cover, and h (cm) is the thickness of the accumulated snow layer. The density p is determined by the results of direct measurements in a pit dug from the daylight surface to the ground, for which special measuring instruments and devices are used; The most standard is the so-called VS-43 weighing snow gauge, which was used on March 18, 2019. The thickness (or power, in glaciological terminology) of snow h is established based on the results of probing the snow layer with multi-section metal or plastic probes, which pierce the entire snow cover to the ground perpendicular to the daylight surface. The number (density) of measurement points depends on the required and methodological accuracy of the applied method for determining h, as well as on the natural variability (variability in area) of the measured parameter. Snow surveys can be areal (optimally - in imitation of the placement of measurements along the nodes of a grid of squares) and route (along a profile of an arbitrary configuration, depending on the set goal of the work). Snow survey on March 18, 2019 was undertaken in the form of a set of measurements h along the line connecting the place where the tent was set up by the Komsomolskaya Pravda expedition with the point of the tent set up by the Dyatlov group, as suggested by the Prosecutor General's Office; the pit was dug directly next to the tent set up on March 18.

Below is a stratigraphic description of the pit (depth levels are given from the day surface downwards). The total thickness of the pit along the wall of the description was 139 cm.

| 0-26 | : | snow slab - fine-grained snow, perfectly white and very dense (ρ=0.39 g/cm3); |

| 26-28 | : | darker and very loose coarse-grained snow (upper suite of the underlying layer); |

| 28-83 | : | rather loose and frozen medium-coarse-grained snow with traces of heterogeneity; |

| 83-106 | : | more dense homogeneous medium-grained snow; |

| 106-114 | : | more loose medium-grained snow; transition to it from the upper layer - by density; |

| 114-116 | : | layer of yellowish medium-grained snow; |

| 116-127 | : | dirtier coarse-grained snow with very large (up to 5 mm) crystals; |

| 127-139 | : | more frozen coarse-grained snow, smaller crystals; variable power over rocks. |

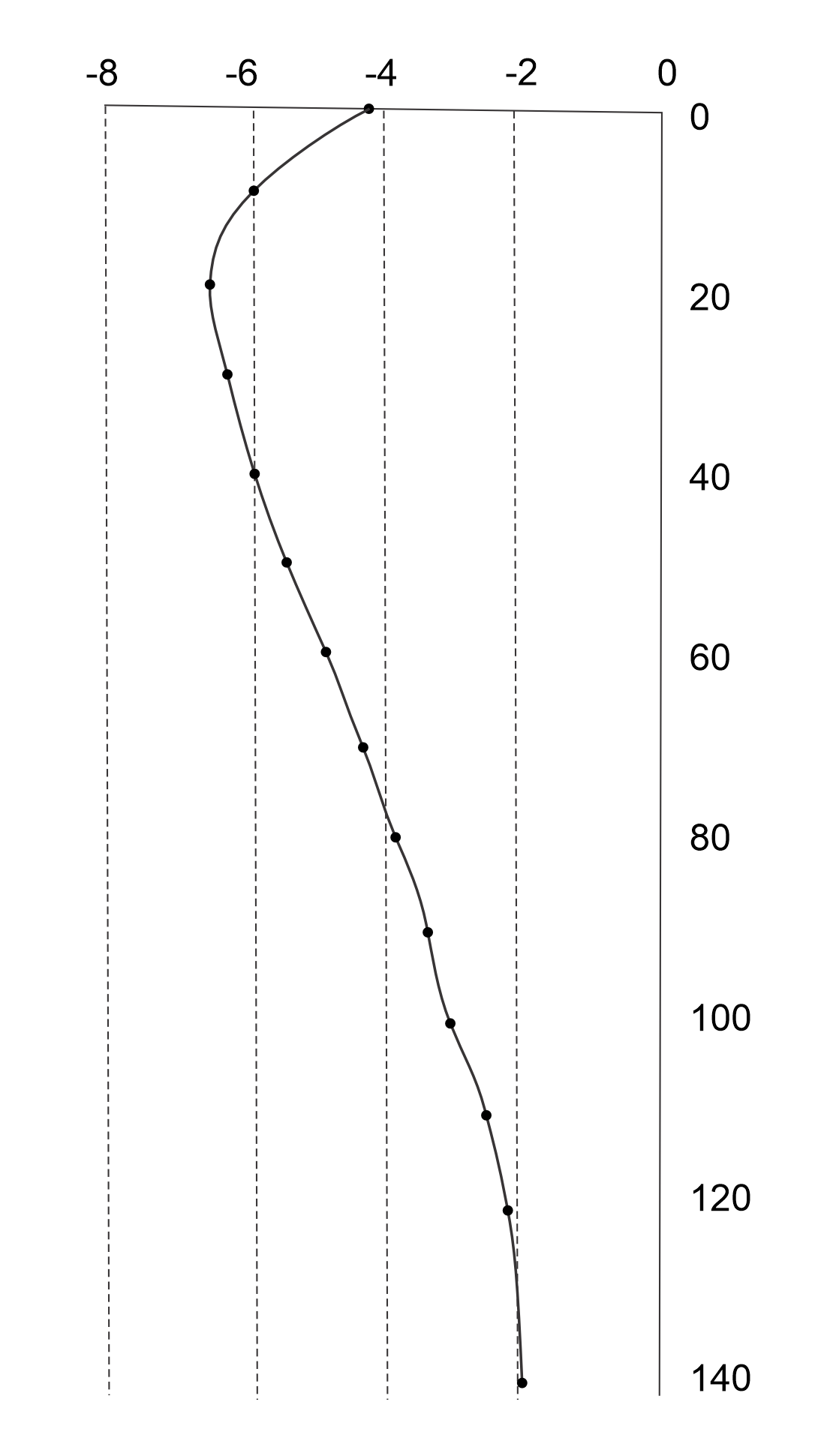

The snow temperature measured in the pit wall every 10 cm of the section was negative at all depth levels (Table 1). The subsurface layer at depths of 15-35 cm was the most frozen, below which the negative temperature values decreased in magnitude towards the base of the pit (Fig. 1).

- 8 -

To measure the density p, we used the sector of the pit face where the snow thickness was 149 cm. Densimetric measurements revealed the following distribution of snow density values (layer by layer):

| 0-50 | - | ρ=0.36 g/cm3 |

| 50-100 | - | ρ=0.39 g/cm3 |

| 100-149 | - | ρ=0.38 g/cm3 |

The average vertically weighted (integral) density was thus 0.38 g/cm3. The thickness of the pit along the wall varied greatly, being predetermined by the nature of the substrate (clusters of stones).

| Depth, cm | Temperature, °С |

| 0 | -4,2 |

| 10 | -6,0 |

| 20 | -6,6 |

| 30 | -6,3 |

| 40 | -5,9 |

| 50 | -5,4 |

| 60 | -4,9 |

| 70 | -4,3 |

| 80 | -3,8 |

| 90 | -3,3 |

| 100 | -3,0 |

| 110 | -2,5 |

| 120 | -2,2 |

| 139 | -1,9 |

Table 1. Snow temperature in a snow pit

Fig. 1. Distribution of snow temperature by depth

The variation of h within the outcrop was characterized by a range of values from 139 to 149 cm. On average, the thickness of the snow cover in the pit was 145 cm. With an average density of p = 0.38 g / cm3 (see above), this is equivalent to E = 546 mm in a water layer. The thickness of the accumulated snow was measured with fiberglass avalanche probes from Pieps with an accuracy of 1 cm. At each measurement point, the readings were duplicated at a distance of approximately 5-10 cm from each other, and their average was taken as the final value. Measurements in the vicinity of the tent erected by the Komsomolskaya Pravda expedition showed a very significant variation in the area of the h parameter, which was determined primarily by the conditions of the subnival microrelief (accumulations of stones under the snow, erosion troughs, etc.). Depending on this, starting from a distance of 3 m from the tent up the slope, the fluctuations in the h values were essentially random, varying in the alignment of the erected tent from 95 to 159 cm. The snow-measuring profile laid directly from the point where the tent was erected by the KP expedition in the northern direction towards the place where, according to the Rosreestr surveyors, Dyatlov's tent stood, reveals a somewhat more regular picture: along this axis the amount of snow gradually increases. This profile consisted of 2 sectors: the first characterized the area where the tent was set up by the KP expedition and where probing was carried out every 50 cm of the distance (5 measurement points); the second reflected snow accumulation on the rest of the profile and consisted of measurement points spaced 4-5 m apart (5 measurement points). The measurement results are presented below in 2 corresponding categories: as snow thickness h normal to the surface and as water equivalent E.

| First sector (along the KP tent) | |

| h, cm: | 96, 105, 150, 159, 169. |

| Ε, mm H2O: | 365, 399, 570, 604, 642. |

| Second sector (from the KP tent to the Rosreestr point) | |

| h, cm: | 181, 198, 196, 227, 243. |

| Ε, mm H2O: | 688, 752, 745, 863, 923. |

Faculty of Geography, Lomonosov Moscow State University,

Ph.D. in Geogr.

/V.V.Popovnin/

Jul 30, 2019